Chinese Nationalist Army 1937-1941.

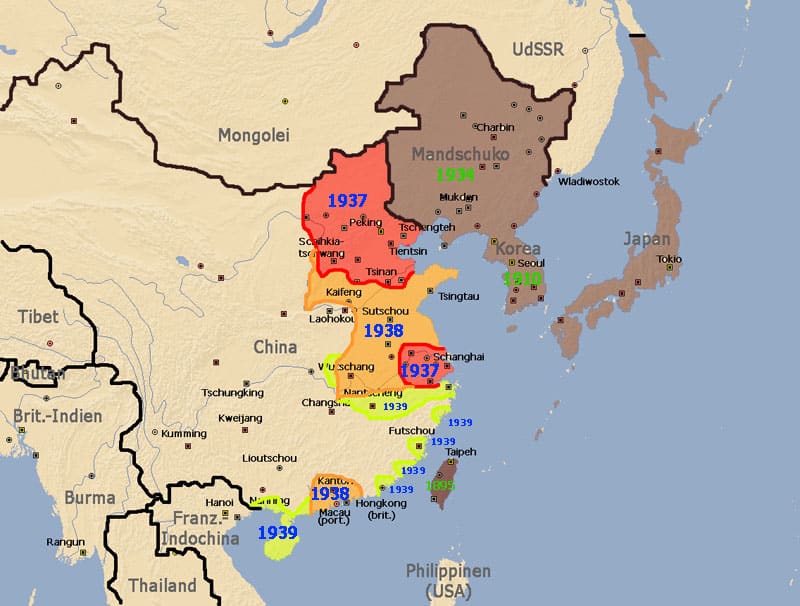

The seizure of Mukden on 19 September 1931 marked the beginning of overt Japanese aggression against China, and from 1937 there was open war. The disorganized Chinese forces were no match on the battlefield for the Japanese armies, but determined resistance prevented a complete collapse. The very size of China precluded a total Japanese victory, and although the Chinese Nationalist government was forced to leave all the major industrial areas and set up a new capital at Chungking, it maintained the struggle, and, in alliance with the communist forces of Mao Tse-tung, tied down enormous numbers of Japanese troops.

Chinese Forces in WW2

Table of Contents

During the Second World War, the Chinese army played an important role in the fight against the Japanese invasion of China, which began in 1937. The Chinese armed forces were mainly composed of two factions:

1) The National Revolutionary Army (NRA) of the Republic of China, led by Chiang Kai-shek and the Nationalist Party (Kuomintang).

2) The Eighth Marching Army and the New Fourth Army, consisting of communist forces under the leadership of Mao Zedong and the Chinese Communist Party (CCP).

Despite the ongoing Chinese civil war between Nationalists and Communists, the two sides nominally joined forces to fight against Japanese aggression as part of the Second United Front. Key aspects of the Chinese army’s involvement in World War II include:

The Second Sino-Japanese War (1937-1945): The Chinese armed forces fought a long, bitter battle against the Japanese invading army, which committed numerous atrocities such as the Nanjing Massacre.

Guerrilla warfare: Communist forces in particular waged effective guerrilla warfare against the Japanese in the occupied areas of China.

Casualties: The Chinese military and civilian population suffered enormous losses during the war, with estimates ranging from 15 to 20 million dead.

The Chinese army’s resistance to the Japanese invasion contributed significantly to the overall Allied war effort, as it tied up a large portion of Japanese forces that could have been deployed elsewhere. After the war, the conflict between the Nationalists and the Communists resumed, eventually leading to the victory of the Chinese Communist Party and the founding of the People’s Republic of China in 1949.

Chinese Nationalist Army

At the outbreak of the Sino-Japanese War in July 1937 the Nationalist Army expanded to about 1.7 million men; its official order of battle included 182 infantry divisions, 46 independent brigades, 9 cavalry divisions, 6 independent cavalry brigades, 4 artillery brigades and 20 independent artillery regiments.

A division had (again, officially) 2 infantry brigades, each of 2 regiments; an artillery battalion or regiment; an engineer and a quartermaster battalion, and small signals, medical and transport units.

In practice, the provision of support and service elements varied greatly from division to division, as did their field strength. The average strength of a division as described above was around 9,000-10,000 men; but this only applied to the ten German-trained divisions re-organized in 1937. The great majority, as well as newly raised or temporary divisions, would average only about 5,000 men. Independent brigades might have about 4,500 men, while their temporary equivalents were perhaps 3,000-strong.

China in 1937 was still a deeply divided country, and the KMT government could not rely on all its nominal forces equally. Rebellions and other disloyalties by various regional military commanders throughout the 1930s had made Chiang Kai-shek very suspicious of a large part of his forces. The most loyal and therefore best-trained and equipped troops were approximately 380,000 men of Chiang Kai-shek’s own pre-1934 army, most of whom had been trained by German instructors. They were commanded by graduates of the Whampoa Military Academy in Canton, which Chiang had himself commanded in 1924, creating an educated and politically reliable officer corps for the KMT army.

Another 520,000-odd men belonged to formations that were traditionally loyal to Chiang, though not of his own creation. Together with this hard core, these gave him a strength of 900,000 men that the government could rely upon. Beyond these armies there existed another class of so-called ‘semi-autonomous provincial troops’ that could sometimes be mobilized in the KMT government’s interest, totaling perhaps another 300,000 men divided between the provinces of Suiyuan, Shansi and Shangtung in the north, and Kwangtung in the south-east.

The rest of the Nationalist army was made up of troops led by commanders who, while having no real loyalty to Chiang Kai-shek, were willing to fight alongside him against the common enemy, Japan. The fighting quality of these troops of questionable loyalty varied from very good to extremely poor. For instance, the 80,000 soldiers and 90,000 militia of the far southern province of Kwangsi were well-led, equipped and disciplined, while the 250,000 soldiers of Szechuan in the south-west were described as the worst-trained and equipped, most undisciplined and disloyal of all Chinese Nationalist troops.

Eroded by casualties – particularly among the trained pre-1937 officer corps – and by poverty of resources, most of these formations were under strength, badly fed, badly cared for, badly clothed and equipped, and badly led, with a combat value comparable to that of the marauding peasants levies of an earlier century. Historically, China’s brutal military culture had given the peasant soldier no reward for victory beyond the opportunity to pillage, and no real emotional stake in any cause beyond his own immediate unit. Caution and cunning were admired, self-respect did not depend upon initiative and dash in the attack or endurance in defense. Unless success came quickly they tended to fall back; on the other hand, even after a headlong retreat in the face of the enemy the long-suffering peasant soldiers could sometimes be brought back to their duty after a short respite.

Weapons of the Chinese Nationalist Army

With an army which quickly rose to over 2 million men, and only a number of small local arsenals and arms factories, the Nationalist army faced a constant problem in arming its troops. By the early 1930s a bewildering array of rifles and machine guns from all over the industrial world had been imported at one time or other by the Chinese. With no central policy on arms purchasing, the various military regions and the virtual warlords who commanded them imported at whim for their own troops. This chronic lack of standardization was only partly addressed by the outbreak of the Sino-Japanese War.

By 1937 the predominant rifle of the Chinese armies was the 7.92mm German Mauser 98k which had been recommended by their German advisers in the early 1930s. The Mauser, imported in large numbers and soon under production in Chinese arsenals, was commonly known as the Chiang Kai-shek rifle. Other rifles based on the Mauser design were also imported from Belgium and Czechoslovakia, as the FN24 and VZ24 in their rifle and carbine forms. The older Mauser Gewehr 88 was also widely used by China, and was produced as the Hanyang 88 in Chinese factories.

Many types of machine guns were also imported during the 1930s – indeed, China was in several instances the only export customer for some of the more obscure European weapons. If an arms’ dealer could not sell his wares to the KMT government, he could always try his luck with one of the provincial army commanders. The predominant Chinese light machine gun was the excellent Czechoslovakian ZB26, imported and copied in large numbers. Other models imported included the Swiss ZE70, the Finnish Lahti, and the Soviet DP26. Machine guns were always in short supply and even the best Chinese forces only had about one-third the allocation per division enjoyed by the Japanese troops.

The Chinese had historically been poor in modern artillery, and most field guns were of the light and mountain classes. Its shortage is illustrated by the fact that in 1941 there were only 800 artillery pieces in the entire Chinese Army. During his early campaigns Chiang Kai-shek had acquired the habit of keeping as much of the artillery as possible under his own control, to weaken any potentially mutinous subordinates. Traditionally the shortfall in conventional artillery had been partly offset by the use of mortars of all calibers.

Basic Chinese divisions:

Strength | German-trained infantry division | normal Infantry division | Independent brigade | Cavalry divsion |

|---|---|---|---|---|

Total units | 10 | 172 | 46 | 9 + 6 Brigades |

Infantry regiments | 4 | ?-4 | 2 | 4 (Cav) |

Total men | 9,529 | c. 5,000 | c. 4,500 | ? |

Machine guns | 324 | 236 (200 light, 36 heavy) | ? | ? |

Mortars | 30 | 18-30 | ? | ? |

Artillery | c. 40 (?) | none | none | none |

References and literature

The Armed Forces of World War II (Andrew Mollo)

World War II – A Statistical Survey (John Ellis)

The Chinese Army 1937-49, World War II and Civil War (Philip Jowett)