The Battle of Britain in 1940-1941.

Operation Sea lion, strengths of the German Navy and Luftwaffe vs RAF, the air battle and the ‘Blitz’.

The Battle of Britain 1940

Table of Contents

Operation Sealion

The Battle of Britain was fought in the air to prevent a seaborne invasion of the British Isles. The German invasion plan, code-named Operation ‘Seelöwe’ (Sea lion), took shape when Britain failed to sue for peace, as Hitler had expected, after the fall of France.

On 16 July 1940, German Armed Forces were advised that the Luftwaffe must defeat the RAF, so that Royal Navy ships would be unprotected if they tried to prevent a cross-Channel invasion.

It was an ambitious project for the relatively small German Navy, but success would hinge upon air power, not sea power.

German Navy in August 1940

- Battlecruiser Scharnhorst under repair after torpedo hit until October 1940.

- Battlecruiser Gneisenau under repair after torpedo hit until November 1940.

- Pocket-battleship Admiral Scheer under repair until September 1940.

- Pocket-battleship Lützow under repair until April 1941.

- Heavy cruiser Prinz Eugen ready.

- Heavy cruiser Admiral Hipper under repair until September 1940.

- Light cruiser Nürnberg ready.

- Light cruiser Leipzig under repair until November 1940.

- Light cruiser Köln (Cologne) ready.

- Light cruiser Emden used as training ship.

- 7 destroyers ready, 3 under repair.

- 19 torpedo boats ready, 1 refitting.

- 23 S-Boats (E-Boats, MTB) ready, 12 under repair.

- 28 U-Boats operational.

There were only some 26 divisions on British home ground, widely scattered and ill-supplied with equipment and transport. The RAF alone could gain the time necessary for the army to re-equip after Dunkirk, and hold off the 25 experienced, well-trained and good equipped German divisions (including two airborne divisions) until stormy fall weather made it impossible to launch Operation Sea lion.

see: British Army and Home Guard in Western Europe and Britain.

The strength of the Luftwaffe before Eagle Day (Adlertag, 13 August 1940)

Luftwaffe: 14 Kampfgeschwader (bomber groups), 8 Jagdgeschwader (fighter groups), 4 Stukageschwader (dive-bomber groups), 3 Zerstorergeschwader (heavy twin-engined fighter groups) in Luftflotte 3 (air fleet 3 commanded by Sperrle from Paris), Luftflotte 2 (air fleet 2 commanded by Kesselring from Brussels) and Luftflotte 5 (air fleet 5 commanded by Stumpff from Norway and Denmark).

1,700 planes serviceable (600 medium bombers; 200 Ju 87 Stuka dive-bombers; 700 Me 109E fighters; 200 heavy Me 110 twin-engined fighters).

Total in the West were 2,287 combat planes: 734 Me 109; 268 Me 110; 336 Ju 87; 949 medium bombers.

Total strength: 3,000 planes (800 Me 109 fighters; 300 heavy Me 110 fighters; 400 Ju 87 Stuka dive-bombers; 1,500 He 111, Do 17 and Ju 88 bombers).

The strength of the RAF before Eagle Day (Adlertag, 13 August 1940)

RAF: 52 fighter squadrons in Fighter Commands 11 (London and Southeast England), 10 (Cornwall and South Wales), 12 (Central England and North Wales), 13 (North England and Scotland) commanded by Air Marshall Hugh Dowding.

960 fighter planes. 704 were Hawker Hurricanes and Supermarine Spitfires (plus 289 reserve planes), the others were the weak Blenheim or Defiant fighters.

Exactly numbers from 8 August: 527 Hawker Hurricanes, 306 Supermarine Spitfires, 82 Bristol Blenheims, 26 Boulton-Paul Defiants (total 941).

350 bombers (including 100 Bristol Blenheims), later 470.

2,000 anti-aircraft guns in 7 anti-aircraft divisions.

21 operational radar stations (in October 1940 there were 40 radar stations operational).

see: Aircrafts and bases of the RAF squadrons in August 1940.

Battle of Britain against the RAF August/September 1940

In July 1940, when the German Luftwaffe stood poised to attack the British Royal Air Force from its recently acquired Channel and North Sea bases, the concept of air power was barely out of its infancy. No full-scale set-piece battle, fought entirely in the air between roughly equal opponents, had taken place before the so-called Battle of Britain (Churchill’s phrase) began over Southern England and South Wales on July 10, 1940. During the next 15 weeks almost every aspect of the philosophy and mechanics of air power and military aircraft design was put to the test.

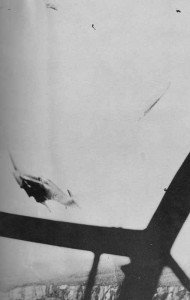

One of the most remarkable pictures of WW2 shows a Hawker Hurricane as it was shot down. At top, the pilot is opening his parachute; right, a wing shot from the plane; center, the Hurricane falling with one wing sheared; lower foreground, the black silhouette of the attacking plane’s window; lower background, the white chalk cliffs of Dover.

The results of the secret ‘electronic war’ were equally unfortunate from the German viewpoint. The radio ‘beams’ directed towards British cities form ground stations on the French coast were invariably detected and ‘jammed’ by the RAF, whereas the latter’s own radar stations gave invaluable early-warning of German bomber formations. The Hurricane and Spitfire squadrons were thus deployed to maximum advantage, eliminating wasteful ‘standing patrols’ over the English coast. The RAF also profited from information gleaned from deciphered Luftwaffe ‘Enigma’ messages.

The Battle of Britain had several phases. During July and August, the Germans engaged the RAF over the Channel in an effort to weaken it by sheer attrition. But the Luftwaffe lost twice as many planes as the British and so began instead to target radar installations and then airfields. This evened the loss ratio to four to three but still failed to clear the skies (211 Spitfires and Hurricanes were destroyed in this ten days and only 40 could be replaced by new planes).

To early, the Germans now took aim at the aircraft factories themselves, a tactic that produced some successes, as when a dozen plants in Coventry were destroyed in November. But the loss ratio climbed back to nearly two to one.

The Blitz

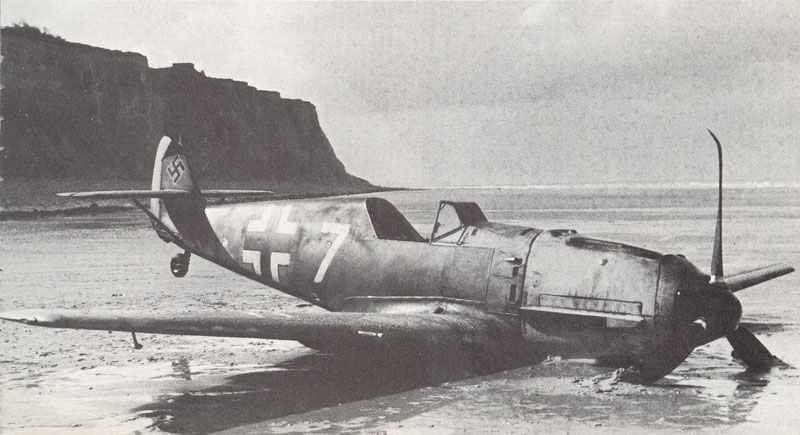

Frustrated by RAF Fighter Command, Hitler indefinitely postponed his projected invasion of Britain (Operation Sea lion) and Goring resorted to improvisation and terror tactics. By day from early October, swarms of Me 109s, many equipped as make-shift fighter-bombers, swept high over the Straits of Dover on hit-and-run raids which, although highly inconvenient and exhausting for the defenders, had no ultimate effect. By night the Luftwaffe engaged in repeated indiscriminate ‘reprisal’ raids on London and other British cities in reply to the early RAF raids on Berlin.

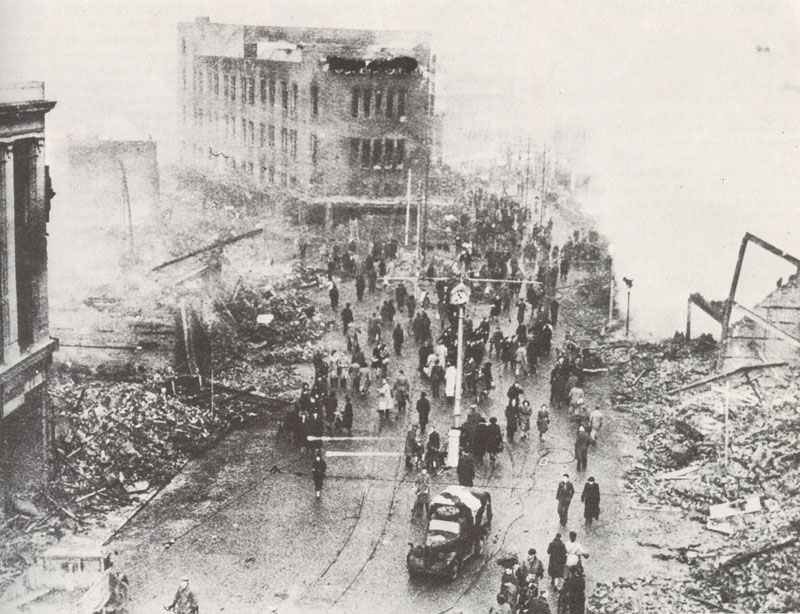

Although the defenses of British cities were still rudimentary, the Luftwaffe failed to exploit this golden opportunity. One reason was its lack of four-engined heavy bombers – comparable with the later British Avro Lancaster – but far more important was the misuse of the available 700 medium bombers. Instead of delivering a limited number of devastating attacks on carefully selected targets (such as aircraft factories or power stations) Goring ordered long processions of bombers to scatter bombs across wide areas of London in the course of all-night raids 10 or more hours in duration. Such tactics meant that the ARP personnel and fireman could deal with individual incidents, and were seldom in danger of being overwhelmed as often happened during the short, sharp, RAF saturation raids on German cities from July 1943.

Equally, underwhelmed was civilian morale, which the conventional wisdom of the 1930s believed incapable of withstanding prolonged aerial bombing. From mid-November 1940, Goring dissipated his efforts even further by sending his night bombers to 15 cities and ports in addition to London.

Though bad weather and muddy French airfields seriously hampered the Blitz during the winter and caused heavy German aircraft losses, the onslaught against Britain was resumed with a vengeance in March 1941 – Glasgow and Clydeside, Plymouth, Belfast, Liverpool and London came in for a series of raids noticeably more concentrated and accurate than previous efforts.

Many feared that this onslaught was the preliminary to the long-feared invasion of Britain. But we now know that it was merely an elaborate diversion to conceal Hitler’s preparations for the invasion of Russia. During the entire Blitz (September 1940 – May 1941), more than 40,000 British civilians were killed (half of them in London), 46,000 seriously injured and well over 1,000,000 houses destroyed or damaged; approximately 2,500 German airmen died in the wrecks of some 600 bombers. In all since July 1940, the Luftwaffe had lost roughly 2,400 aircraft but had failed either to gain air superiority – the vital precondition for a successful German invasion – or to terrorize the British people into submission.

References and literature

Der Grosse Atlas zum II. Weltkrieg (Peter Young)

Chronology of World War II (Christopher Argyle)

Das große Buch der Luftkämpfe (Ian Parsons)

Luftkrieg (Piekalkiewicz)

Die Schlacht um England (Bernard Fitzsimons, Christy Campbell)

World War II – A Statistical Survey (John Ellis)