German Armored Cruisers Scharnhorst class from World War One, and the battle of the Falklands (part II).

History, development, service, specifications, pictures and 3d model.

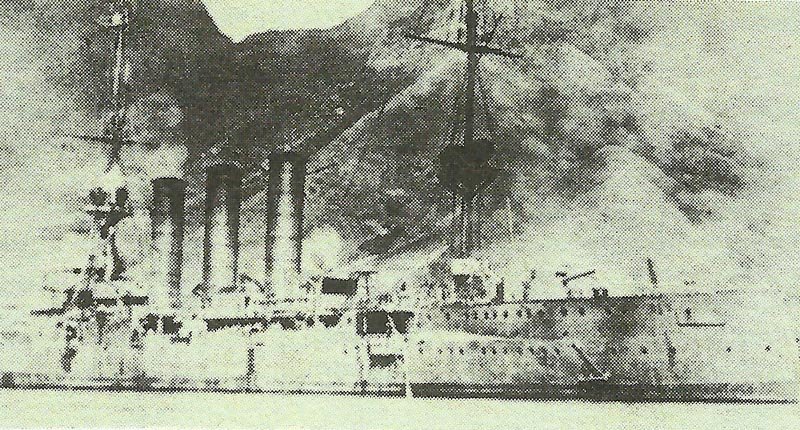

The armored cruiser SMS Scharnhorst was the flagship of Graf Spee’s East Asia squadron with the base in Tsingtao. In consideration of the British naval rule, the meteoric rise of the sea hero von Spee and his squadron could only end in the same way. But before he could be cornered, he gave the British Royal Navy the first major defeat at sea in two and a half centuries.

Battle of the Falklands on December 8, 1914

Table of Contents

The Battle of the Falklands was a significant naval engagement that took place during World War I on December 8, 1914. It was fought between British and German forces in the South Atlantic, specifically near the Falkland Islands.

Overview

Prior to the battle, the German East Asia Squadron, commanded by Vice Admiral Maximilian von Spee, had been conducting operations in the Pacific and South Atlantic.

In response, the British Admiralty dispatched a task force under Vice Admiral Doveton Sturdee to confront von Spee. This force included several modern warships, such as the battlecruisers HMS Invincible and HMS Inflexible, along with other cruisers.

On the morning of December 8, the British fleet encountered the German squadron near the Falkland Islands. The British ships were better armed and equipped, and the battle quickly turned in their favor. The engagement began with long-range gunfire, and the British ships effectively targeted the German vessels.

Warships Involved

British Royal Navy:

– HMS Invincible – Battlecruiser (Flagship)

– HMS Inflexible – Battlecruiser

– HMS Carnarvon – Armored Cruiser

– HMS Kent – Armored Cruiser

– HMS Cornwall – Armored Cruiser

– HMS Glasgow – Light Cruiser

– HMS Bristol – Light Cruiser

– HMS Macedonia – Armed Merchant Cruiser

Vice-Admiral Sir Doveton Sturdee was in overall command of the British forces. The presence of two modern battlecruisers provided the British with a significant advantage in terms of speed and firepower.

Imperial German Navy (East Asia Squadron):

– SMS Scharnhorst – Armored Cruiser (Flagship)

– SMS Gneisenau – Armored Cruiser

– SMS Nürnberg – Light Cruiser

– SMS Dresden – Light Cruiser

– SMS Leipzig – Light Cruiser

Vice-Admiral Maximilian von Spee commanded the German forces. While von Spee’s ships were well-handled and had achieved previous successes, they were generally outmatched by the British battlecruisers in terms of speed and artillery range.

The Germans suffered significant losses, with several ships being sunk, including the armored cruisers SMS Scharnhorst and SMS Gneisenau. The battle lasted only a few hours, resulting in a decisive victory for the British.

The Battle of the Falklands was a crucial moment in the naval aspect of World War I. It effectively eliminated the German East Asia Squadron as a threat and secured British control over the South Atlantic. This victory also boosted British morale and demonstrated the effectiveness of their naval power.

The battle highlighted the importance of modern naval technology and tactics, as well as the strategic significance of maintaining control over key maritime routes during the war.

Course of the naval battle

The British Royal Navy had suffered a devastating defeat in the Battle of Coronel. Nevertheless, von Spee seemed to be unenthusiastic about his success. Although he had suffered no significant damage (only six minor hits and two wounded men), he used almost half (42 per cent) of his ammunition for the heavy guns.

Now there was little prospect of more success, he was still 10,000 miles (16,000 km) away from home, and he was too aware that the world’s largest naval power, after her historic naval defeat, would now do everything in its power to bring him down. His squadron was doomed and von Spee knew it.

The day after the battle of Coronel, he arrived in Valparaiso to load coal, but refused to take part in the victory celebrations in his honor.

For a short time he had brought the trade of nitrate, copper and tin from Chile and Peru to a standstill and sunk two British armored cruisers, while otherwise the Allied trade in the region of La Plata continued undisturbed.

It may have been possible to quickly circumnavigate Cape Horn and then erupt into the vastness of the South Atlantic to improve the likelihood of his escape, but von Spee seemed to have been plagued by a certain indecision again.

First he wasted his time at the remote island of Mas-a-Fuera and then anchored off the desolate Chilean coast north of the Magellan Strait.

It was not until 26 November, 25 days after the Battle of Coronel, that he ran full speed towards the Falkland Islands. There he wanted to destroy the important radio station and the remains of Cradock’s squadron, capture the British governor and destroy all stocks he didn’t need for his own use.

Although it was now summer in the southern hemisphere, there was terrible weather around Cape Horn and the squadron did not circumnavigate it until the night of December 1 to 2, 1914. Early in the morning of December 2, a Canadian sailing ship loaded with coal was sighted. Since von Spee always thought of his long way home, he brought the ship into sheltered waters and spent three days reloading its coal.

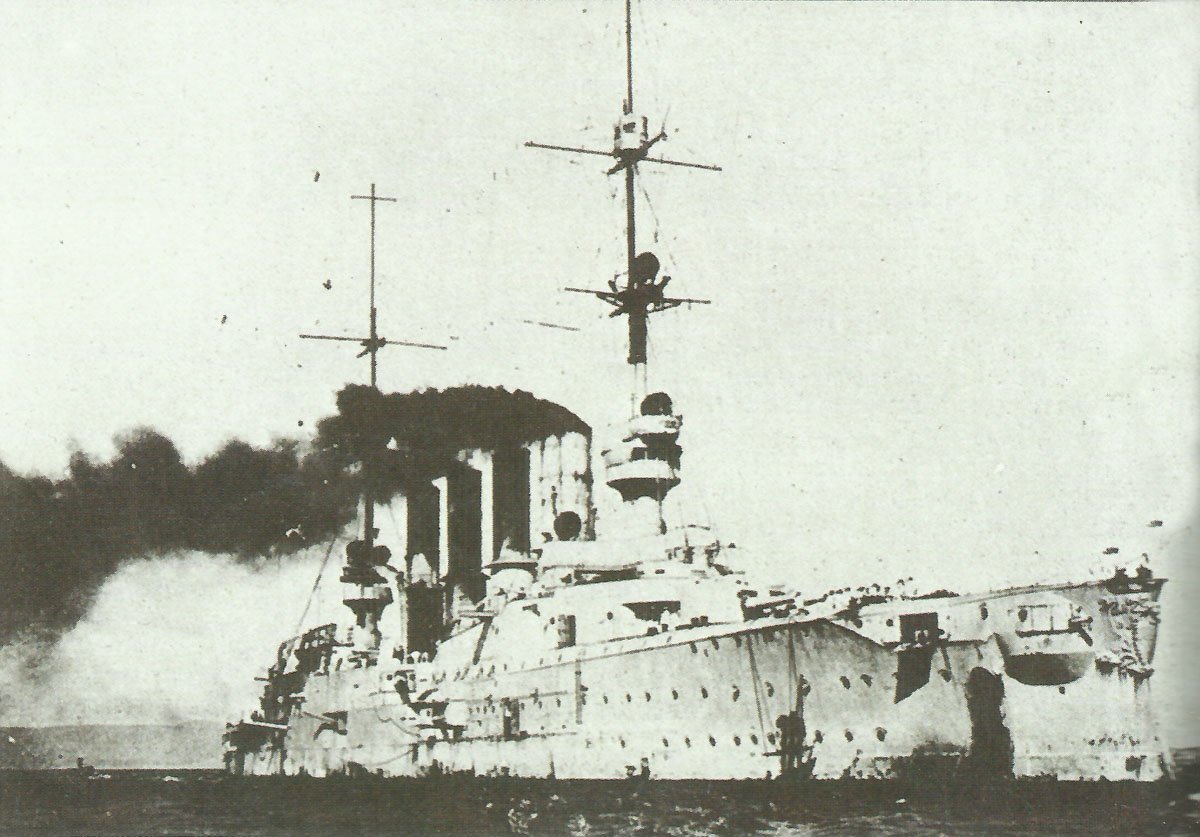

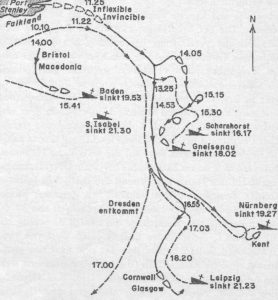

The morning of 8 December 1914 began with bright light and clear weather. At this time, Gneisenau, supported by the following Nuremberg, was on his way off the coast of Eastern Falklands towards the port of Stanley, while von Spee with the rest of the squadron approached from the south.

The main batteries were already aligned on the radio station when suddenly the water splashes of a volley of two shots of large-caliber cannons were seen in front of the German ships ahead of the coast. A second volley followed, which hit close enough to hurl fragments of shells onto the upper deck of the Gneisenau.

The two German ships running along the coast finally circumnavigated the promontory that protected the harbor. At 9:40 their crews could then see the smoke and the high tripod masts, which could only belong to British capital ships. Von Spee had wasted too much time !

After the disaster at Coronel, the British admiralty had reacted quickly and sent three battlecruisers from the Grand Fleet. Two of them, HMS Invincible and Inflexible, had just arrived with four cruisers at Rear Admiral Stoddart’s cruiser squadron and were still bunkering coal.

In addition to the two battlecruisers, the entire British squadron consisted of the Defence, Kent, Carnavon and Cornwall armored cruisers, as well as the Glasgow and Bristol light cruisers.

Fortunately for the British commander, Vice Admiral Doveton Sturdee, the old battleship HMS Canopus, which had arrived too late for the Battle of Coronel, had been grounded as a floating harbor battery. Through its indirect fire on the Gneisenau, it bought the unprepared British forces time to become ready for battle.

Gneisenau and Nuremberg now joined to the rest of the German squadron and the ships of Admiral von Spee hastily and in loose formation made their way southeast of the Falklands. Thus, he missed his only chance to fight the unprepared British squadron with some success inside the harbor.

In the meantime none of the German ships could run at its construction speed anymore, since engine problems and contamination of the hulls had occurred during the long voyage, which could not be fixed without a base.

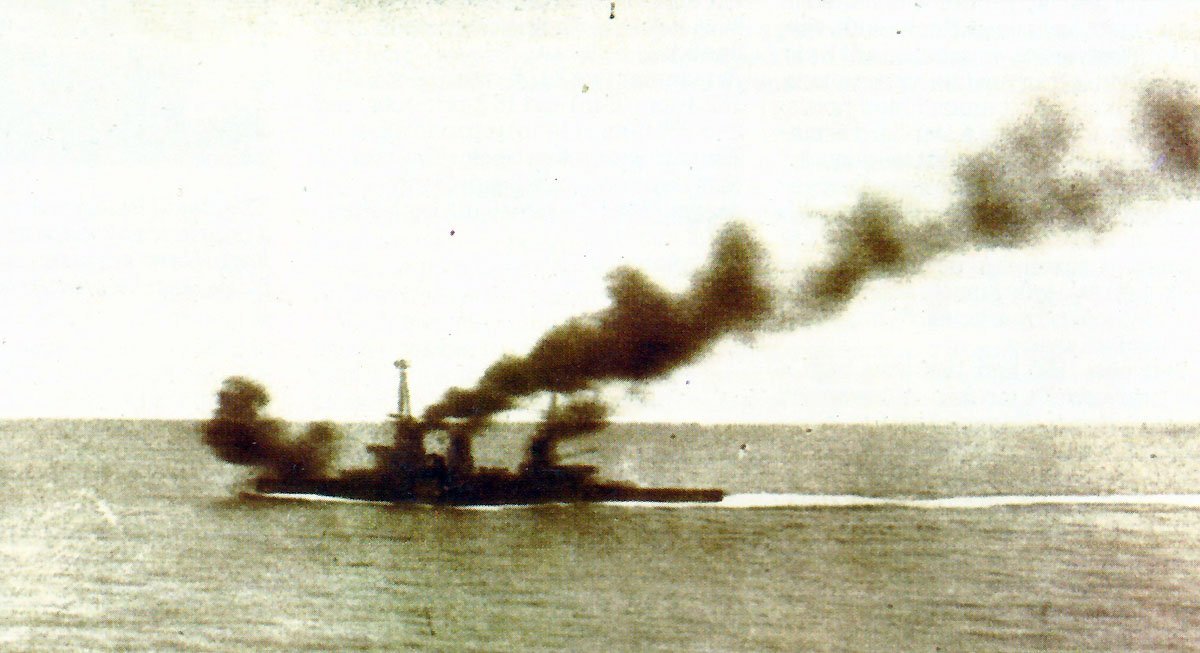

Even before they had disappeared over the horizon, the German crews could already see the first British ships leaving Port Stanley. They only had a head start of 15 nautical miles and the visibility was perfect, the day was still young and their destruction seemed now only a matter of hours.

The light cruiser Leipzig began to slow down, but the urgency of the squadron’s escape became clear from the permanently approaching smoke clouds of the British squadron, which was not even in a great hurry.

At 12:47 p.m. the firing began with the first salvo of the 12 inch (305 mm) guns of the leading British battlecruiser, the Invincible. At 13 o’clock the German ships were surrounded by shells hitting into the water and were not able to shoot back because of their smaller firing range.

At 13:20, although Spees’ ships had still not sustained significant damage, he realized that his situation was hopeless if he held the squadron together. So he decided to send away his light cruisers and leave them to themselves so that they might have a chance to escape. However, he could see that the British cruisers were now pursuing them, while his two armored cruisers were still being followed by the battlecruisers.

In order to reduce the combat distance, he turned abruptly and rushed to the aid of Leipzig, which had already been badly hit. After only ten minutes, he was within his 13,125 yard (12,000 meter) fire range of the pursuers. After the firing was opened, Scharnhorst quickly hit the Invincible.

The British reaction, however, was simple, to increase the distance again with its greater speed and to continue the fire. The British now stayed at a greater distance and intended to use as much ammunition as necessary. Gneisenau now had a grace period from her big opponent Inflexible, which had only poor visibility due to the smoke clouds of the lead ship.

Now longer pauses between firings occurred when both sides tried to work out advantages by maneuvering. But at 3 pm the weather got worse and the British were looking for the decision.

The distance fell to 12,000 yards (10,975 metres), which allowed Spees armored cruisers to use their 15 cm (5.9 inch) secondary guns, but also made the effect of heavy British artillery at short range decisive.

The Scharnhorst ran violently burning and forward under the loss of the third funnel. When the fire of their guns subsided, it was also the turn of the Gneisenau.

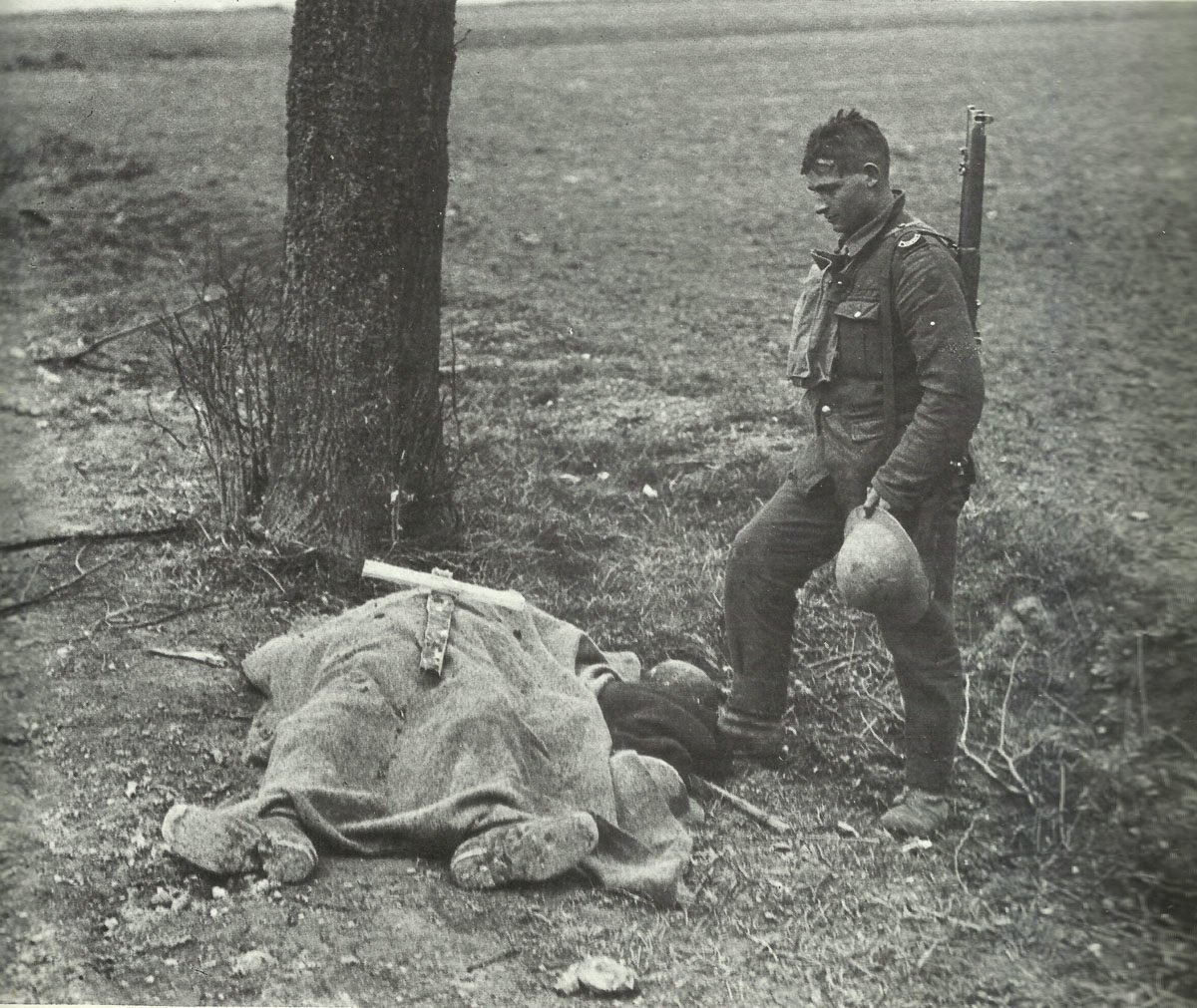

Von Spee’s flagship ignored all calls to surrender and Scharnhorst capsized like a blown fire at 16:17. There were no survivors.

The Gneisenau continued the hopeless fight and although a cloud of drizzle now descended, her crew saw the four funnels of HMS Carnarvon armored cruiser coming up alongside the two British battlecruisers.

The darkness gave her no protection from the enemies fire and after more than fifty hits of heavy caliber, the foremost funnel was already leaning against the second, the foremasts bullet away and swaying she stopped in the smoke of her own smoke.

In the meantime, the British battlecruisers had shot almost their entire ammunition and at short range they fired another 15 carefully targeted shots into the wreck.

The commander ordered the tide valves to open, while the survivors of the Gneisenau gathered on deck, raised the emperor three times and left their ship. Only two hundred men could be rescued from the ice-cold water.

Of the light cruisers, only Dresden managed to escape for a few more months. Kent caught up with Nuremberg (where the second son of Admiral von Spee also dies) and sank them at 19:27, while the same fate struck Leipzig (18 survivors) at 21:23 by Glasgow and Cornwall. Only one of the three German coal ships escaped and was interned in Argentina, while Baden at 19:53 and St Isabel at 21:30 were sunk by Bristol and Macedonia.

The battle of Coronel was terribly avenged. The British squadron suffered only minor losses and damage, confirming the obvious superiority of battlecruisers over armored cruisers.

The battle of the Falklands was fought only by artillery and remained practically the only total victory in the naval war of the First World War, if one considers the later self-sinking of the Light Cruiser Dresden after trapped by Kent and Glasgow in March 1915 at the Juan Fernandez Islands.

However, apart from the fact that the British battlecruisers had to consume practically their entire stockpile of heavy artillery ammunition, it is also remarkable that the naval battle at the Falklands also demonstrated the toughness of the German warships, their surprisingly large artillery range and the extraordinary fighting spirit of their crews.

Animation 3D model armored cruiser Scharnhorst

References and literature

Jane’s Fighting Ships of Word War I

Kriegsschiffe von 1900 bis heute – Technik und Einsatz (Buch und Zeit Verlagsgesellschaft)

The Illustrated Encyclopedia of Weapons of World War I (Chris Bishop)

Atlas zur Seefahrts-Geschichte (Christopher Loyd)

Seemacht – eine Seekriegsgeschichte von der Antike bis zur Gegenwart (Elmar B. Potter, Admiral Chester W.Nimitz)

History of World War I (AJP Taylos, S.L. Mayer)