The British Army in World War One, 1914-18.

Uniforms, organization, leaders, strength and casualties.

British Army in World War One

Table of Contents

Overview

The British Army played a significant role in World War I, which lasted from 1914 to 1918. At the beginning of the war, the British Army was a small, professional force, but it quickly expanded through volunteering and later conscription to meet the demands of the conflict.

Key aspects of the British Army in World War I:

Western Front: The British Army fought primarily on the Western Front in France and Belgium, engaging in trench warfare against German forces. Major battles included the Somme (1916), Passchendaele (1917), and Cambrai (1917).

Gallipoli Campaign: In 1915, British and Allied forces attempted to capture the Gallipoli Peninsula in the Ottoman Empire to secure a sea route to Russia. The campaign was a failure, resulting in heavy casualties.

Middle East: British forces also fought against the Ottoman Empire in the Middle East, including the Mesopotamian Campaign and the Sinai and Palestine Campaign, which resulted in the capture of Baghdad and Jerusalem.

Dominion and Colonial troops: Soldiers from British Dominions (Canada, Australia, New Zealand, Newfoundland, and South Africa) and colonies (such as India) made significant contributions to the war effort, serving alongside British troops.

Technological advancements: The British Army adapted to the new realities of modern warfare, employing technologies such as machine guns, tanks, and aircraft.

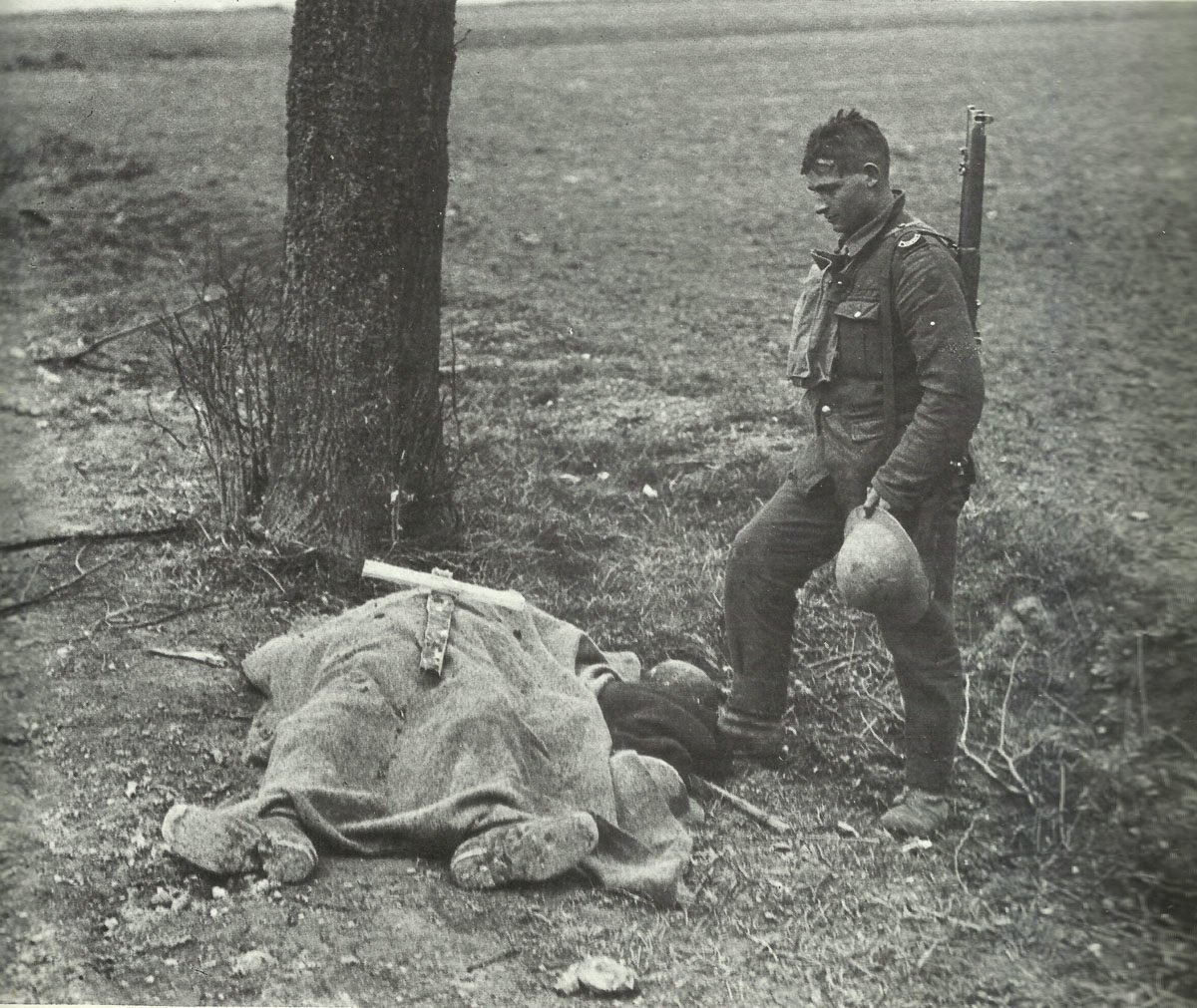

Casualties: The British Army suffered heavy casualties during the war, with over 880,000 soldiers killed and more than 1.6 million wounded.

The experience of World War I had a profound impact on British society and the British Army, leading to significant social, political, and military changes in the post-war era.

The British army at the outbreak of war

When in 1914 war was declared, there were those who thought that the Expeditionary Force should remain in Great Britain, or should go direct to Belgium in fulfillment of the British guarantee of neutrality, but it was too late now to change, and on 6th August the cabinet decided that it should go to France as planned, but without two of its divisions which would for the present remain in Great Britain.

Although small, the British army was well-trained and equipped On the South African veld Boer bullets had taught it something of the reality of firepower. Now, the marksmanship of the infantry was in an entirely different class from that of continental armies. The cavalry, too, were armed with a proper rifle, not the neglected carbine of continental cavalry, and knew how to use it, but their peacetime reaction was setting in and the glamorous, futile charge coming back into fashion.

Continuing an old tradition in modern shape, the Territorial Force and the Yeomanry had been organized by Haldane into a second-line army of fourteen divisions, far from fully trained or equipped, but a good deal more effective than many realized. Beyond that there were the older reservists and the militia as replacements, and the distant imperial garrisons and armies of India and the dominions.

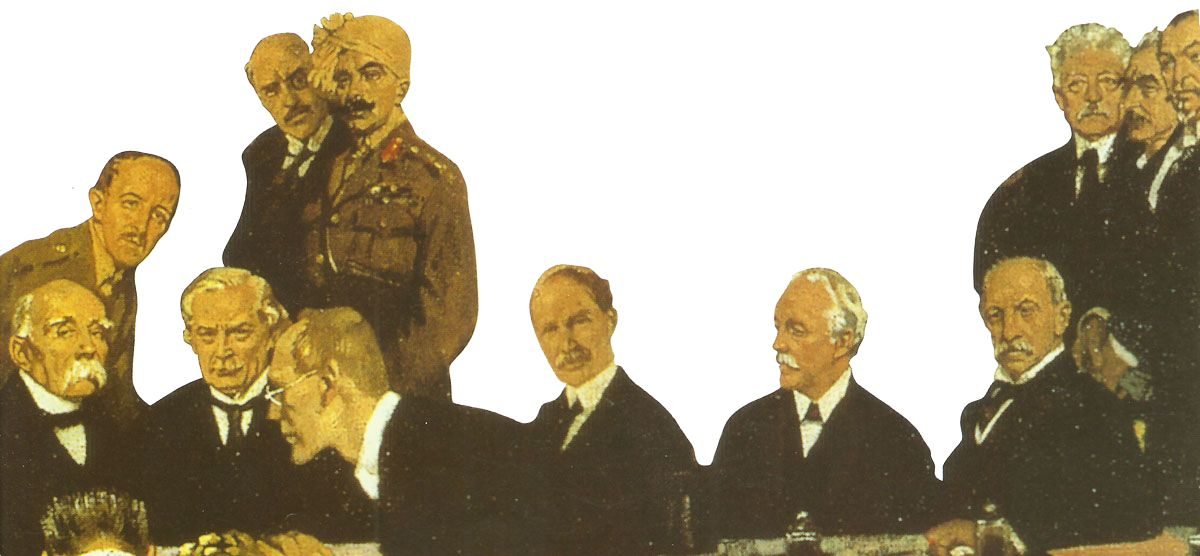

Field Marshal Sir John French, commander-in-chief, British Expeditionary Force, had been a successful cavalry commander in South Africa, but at sixty-two was showing his age. Lieutenant-General Sir Douglas Haig, commanding the I Corps, French’s chief-of-staff in South Africa and Haldane’s assistant in the subsequent reforms, was able and ambitious, but inflexible and wedded to cavalry doctrine. Kitchener, now Secretary of State for war, a tremendous national figure, had flashes of insight amounting almost to genius but little appreciation of staff organization or civilian control. In general, British officers were efficient and devoted but narrow in outlook. However, a far higher proportion of them than of officers in France and Germany had experienced the reality of war.

GREAT BRITAIN (August 4, 1914 – November 11, 1918)

- Soldiers available on mobilization = 800,000

- Army strength during the war = 5,704,000

- KIA Military = 997,000

- Wounded Military = 2,300,000

References and literature

History of World War I (AJP Taylos, S.L. Mayer)

Army Uniforms of World War I (Andrew Mollo, Pierre Turner)

World War I Infantry in Colour Photographs (Laurent Mirouze)

The British Army 1914-18 (D.S.V. Fosten & R.J. Marrion)

The Illustrated Encyclopedia of Weapons of World War I (Chris Bishop)

An Illustrated History of the Weapons of World War One (Ian Westwell)

Die Geschichte der Artillerie (John Batchelor, Ian Hogg)