The monthly days of 1939:

Table of Contents

The year 1939 – Countdown to World War Two.

‘Peace in our time’

In a today infamous broadcast on September 28, 1938, Chamberlain reported: ‘How horrible, fantastic, incredible it is that we should be digging trenches and trying on gas masks here because of a quarrel in a faraway country between people of whom we know nothing.’

Of course this so-called ‘quarrel’ had been evidently resolved 2 days afterwards by the Munich Agreement the outcome wasn’t ‘peace in our time’ – as believed by Chamberlain – however a 5 1/2 month breathing time.

Loaded with disregard and disapproval at the gullibility of the ‘friendly aged man’ exactly who he previously easily offered his ‘autograph’ at Munich, Hitler increased propaganda and subversion versus Czechoslovakia and openly confronted to blast Prague into ruins if the frightened President Hacha didn’t accede to his requests. On March 15, 1939, Hacha agreed upon a statement in Berlin that ‘to achieve ultimate pacification, he confidently placed the fate of the Czech people and country in the hands of the Fuehrer of the German Reich.’

End of Appeasement

The ‘Rape of Czechoslovakia’ on March 15, 1939, did force the British and French Governments to give up Appeasement forth-with. In just 2 days, Chamberlain published an official disapproval.

This was followed, at the end of similar month, by an Anglo-French warranty of aid to Poland – obviously Hitler’s upcoming target – ‘in the event of any action which clearly threatened Polish independence, and which the Polish Government accordingly considered it vital to resist with their national forces … to lend the Polish Government all the support in their power’.

On April 26, as a result of Mussolini’s occupation of the small country of Albania, Britain reintroduced conscription, as radical a measure in peacetime military policy as the guarantee to Poland had been in her foreign scheme.

Italy and Germany changed their Axis right into a proper military partnership. Britain and France worked out pacts with Greece, Turkey and Romania. Hitler, at the same time, had been active arranging the annexation of Danzig, the Polish Corridor, as well as the termination of Poland. The Wehrmacht was publicly instructed to be prepared for all scenarios by August 25, 1939.

A single significant topic nevertheless still existed. Whatever roles were America and Stalin’s Russia planning to participate in the imminent war ?

There seemed to be little question concerning the USA for the foreseeable future. Controlled by 3 self-imposed Neutrality acts, a nevertheless isolationist America was being slowly influenced by Roosevelt to consider a lot more interest in Europe instead of the 2-year-old Sino-Japanese War.

There seemed to be a lot more debate of the strategy to be followed by Russia. The so-called ‘Peace Front’ which France and the UK were being creating and which at this point incorporated Poland, Romania, Greece and Turkey, could not be a successful prevention without Russia. Russian and British diplomats involved in regular, friendly however pointless talks. The Communist Press quit in order to denounce Chamberlain for his believed disloyalty of Czechoslovakia as well as the London Times was uncommonly quiet about the disadvantages of Russian politics.

At the beginning of June William Strang, a top official at the Foreign Office as well as a specialist in Soviet matters, travelled as special emissary to Moscow to start talks about an Anglo-Russian agreement.

Stalin’s double game

However, for people who had eyes to discover, Stalin was actively playing a double game. Within an important speech on April 28, 1939, cancelling the German-Polish Pact of 1934 as well as the Anglo-German Naval Agreement of 1935, Hitler had skipped over the typical sentences about the ‘Jewish Bolshevism’ along with the ‘sub-human monsters’ inhabiting the Kremlin. On May 3, the diplomatic Anglophile Litvinov had been abruptly exchanged as Commissar for Foreign Affairs by the provincial and harsh Molotov. A few days afterwards a different Russian ambassador found its way to Berlin to a remarkably friendly reception.

French and British staff officers, sent out to Moscow at the beginning of August to start discussions with Marshal Voroshilov, quickly discovered themselves performing versus unexplainable obstructions and delays. Voroshilov requested agreement to Russian military power over the Baltic States and there were interminable quarrels over acceptable military counter-measures in opposition to ‘indirect aggression’.

The Baltic States were averse to compromising their neutrality and preferred to settle independent nonaggression pacts with Germany. Poland nevertheless clung to her common Russo phobia.

Then on August 19, 1939, Stalin declared to the Politburo his firm purpose to establish a pact with Germany. On August 21, the upcoming realization of a Russian-German Pact had been reported in Berlin to a shocked globe.

The whole day, the French and British officers in Moscow made an effort to speak to Voroshilov. However, when the head of the French Military Mission in the end talked to the Russian marshal he had been addressed by an unpleasant lesson: ‘The question of military collaboration with France has been in the air for several years, but has never been settled. Last year, when Czechoslovakia was perishing, we waited for a signal from France, but none was given. Our troops were reedy … The French and English Governments have now dragged out the political discussions too long.’

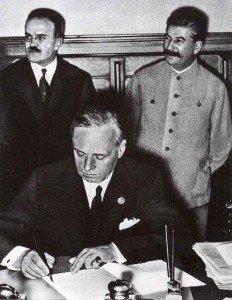

The following day, Hitler’s pompous Foreign Minister, von Ribbentrop, came to Moscow for the ceremonial finalizing of the German-Russian Nonaggression Pact.

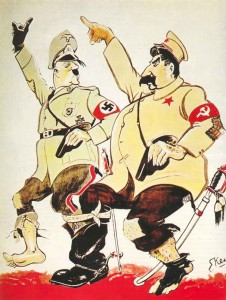

The ‘unnatural’ Hitler-Stalin Pact

Even though initially look the Pact seemed to be (in Churchill’s words) ‘such an unnatural act’, it were built with a specific Machiavellian sense.

Stalin had been decided to stay away from the approaching European war and leave the fighting to the Western democracies and Germany. This was especially crucial considering that the Russian leader had not long ago emasculated the Red Army by purging and liquidating a huge number of senior officers.

Stalin thought that the democracies had always aspired to involve in a war against Germany, and that they expected to arise unharmed and superior from a German-Russian conflict of annihilation.

The democracies in the same way strongly considered Stalin to be playing the same game with Germany and themselves. Hitler, for his aspect, wasn’t completely sure by the Anglo-French promise to Poland, and thought about the concept of setting up one more ‘Munich’. Considering he was resolute to destroy Poland and risk the greater war in the West, he was previously primary to get Stalin’s neutrality – or even better, his complicity and benevolence – and in doing so get rid of his biggest worry – a war on two fronts like in World War One 1914-18.

The democracies, understanding completely that one more surrender to Germany would cause an ultimate and irredeemable damage to their reputation and power, had been settled no matter what to aid Poland.

However, they had not much to offer Stalin other than boring reassertion of the doctrine of collective security, in which he no longer had any trust, and were legally precluded from trafficking in the independence of small nations in Eastern Europe.

Poland’s fate is sealed

The circulated content of the German-Russian Pact had been easy and brief. The two parties undertook to avoid any kind of act of force against each other; never to assistance any 3rd Power that made either of them ‘an object of warlike action’; to confer with any problems of common interest; as well as negotiate any kind of upcoming differences ‘by the friendly exchange of views’.

The Pact included no ‘escape clause’ and it was to be valid for 10 years.

Within a top-secret codicil Germany offered Russia carte blanche in Finland, Latvia and Estonia, but insisted that Lithuania should be in her sphere of influence.

Poland ended up be partitioned, Germany getting the lion’s share, which includes the Polish Corridor, Danzig, Cracow, Upper Silesia as well as Warsaw, while Russia was to reoccupy western Belorussia along with the western Ukraine, the two previously being Russian territory until 1920.

Pretty much everything had been hardly plausible to Western brains. Even the Russian and German people had been shocked and the Japanese Government briefly broke off talks for a military partnership with Germany.

On August 25, Britain revealed her previously promise to Poland in a proper Anglo-Polish Alliance. Appeals to Hitler from Chamberlain and Roosevelt, a papal peace message and offers of mediation from King Leopold III of Belgium and Queen Wilhelmina of the Netherlands were heeded by an eleventh-hour intervention from Mussolini. The Duce, intending to duplicate his success as the ‘honest broker of Munich’, suggested that a five-Power meeting should join on September 5 to ‘examine the clauses in the Treaty of Versailles which are at the root of the (German-Polish) trouble’.

Paradoxically, what in fact delayed the German attack on Poland by a few days was Hitler’s last-minute finding that Mussolini wasn’t intending to complete his military partnership with Germany.

On August 29, Hitler commanded a Polish emissary with total powers to settle the troubles of the Corridor and Danzig. This was an unmistakable mirror of earlier requests to Czechoslovakia and Austria, and the Polish Government rejected. More German suggestions, by means of an ultimatum, had been ready, however they never ever arrived at – and were by no means supposed to reach – the Polish Government soon enough.

At daybreak on Friday, September 1, 1939, German troops invaded Poland by air, land and sear. Absolutely no declaration of war had been made, but Ww2 had started.