Special Japanese Kamikaze aircraft and their pilots in the Second World War.

Development, deployment, specifications and pictures of Yokosuka MXY-7 Ohka and Nakajima Ki-115 Tsurugi.

Yokosuka MXY-7 Ohka

Table of Contents

Type: Japanese single-seat rocket-powered Kamikaze aircraft Yokosuka MXY-7 Ohka.

In the last months of the Second World War a total of 852 Ohkas were built in four versions.

It was in the summer of 1944 when, in view of the overwhelming and rapidly increasing strength of the Allies on the Pacific theater of war, the Japanese naval staff first considered the concept of suicide strikes to ward off enemy attacks. Once the Imperial Navy had officially adopted the principle of the Kamikaze suicide attack, it was only logical to design an aircraft for this particular task rather than using inefficient, more vulnerable and expensive conventional machines with a less devastating effect.

Ensign Mitsuo Ohta was the first to produce a rough design for a guided flying bomb and the Yokusaka company was commissioned to carry out the detailed plans and completion.

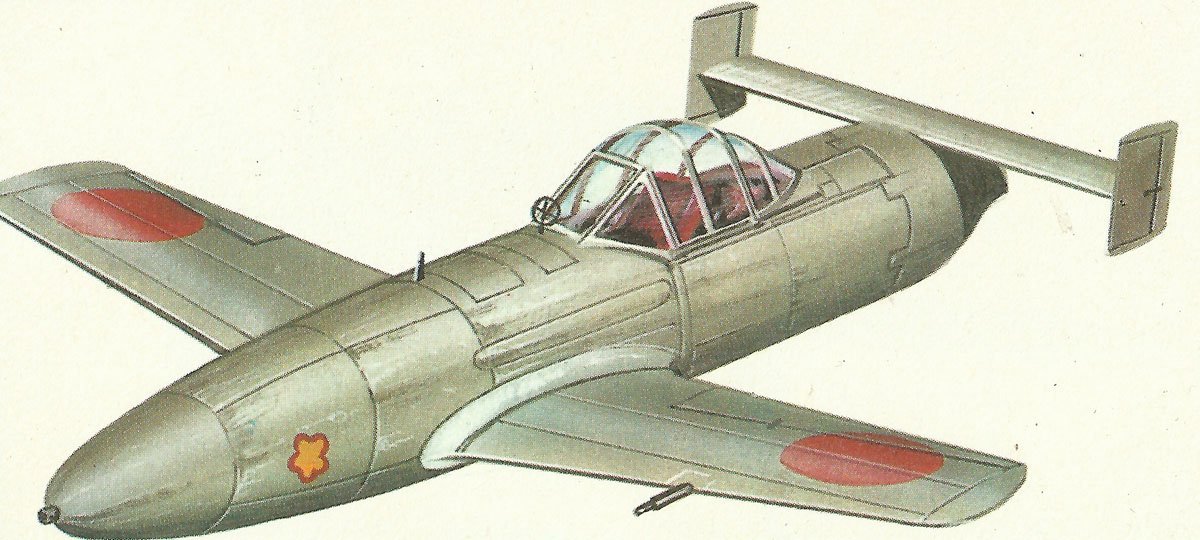

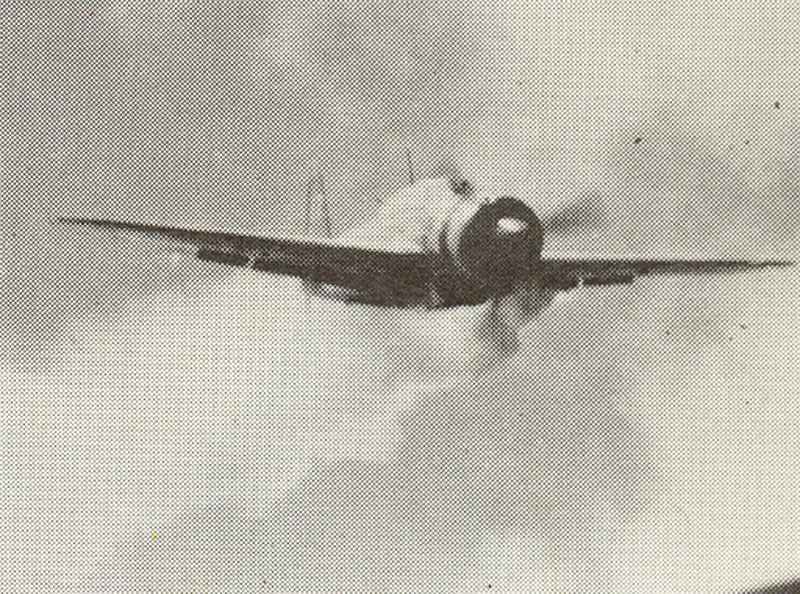

The MXY7 (known as the ‘Baka’ in Allied code, which means ‘fool’ in Japanese) was not so much an aircraft as a flying bomb powered by a rocket or jet engine.

The project was started in the summer of 1944 and the Ohka was made mainly from cheap wood, with three solid-fuel rockets in the rear fuselage and a 2,446 lb (1,200 kg) warhead in the nose.

First test flights began near Sagami in October 1944, followed by unmanned flights with the rocket engine the following month. Series production then began.

Originally intended for coastal defense, the Ohka was later modified into an offensive weapon. In the process, the MXY7 Model 11 was dropped from a carrier aircraft, usually a Mitsubishi G4M Betty without bomb doors, about 50 miles (80 kilometers) from the target. The Kamikaze pilot, who was locked in his cockpit before the launch of the carrier aircraft, then went into a fast glide flight at about 290 mph (466 km/hr) and ignited the rocket electrically, while he went into a steep final approach for the last 30 seconds of the flight path.

The first mission was supposed to take place on 21 March 1945 by the 721st Kokutai, but the carrier aircraft was intercepted by American fighters and had to release its Ohka too early.

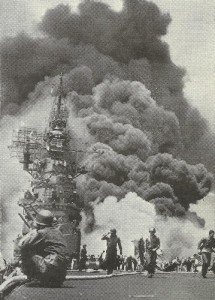

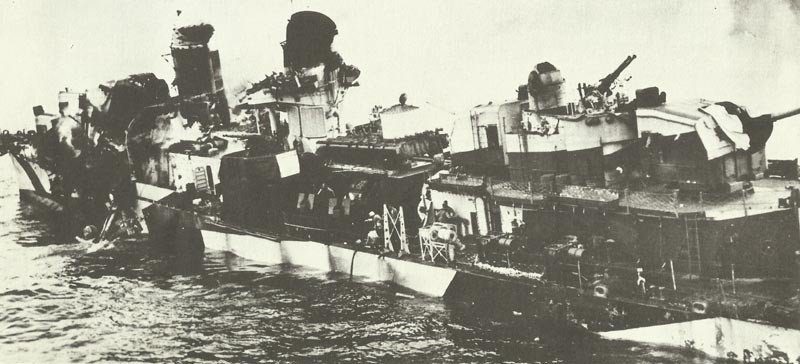

The first success of the Ohka (Japanese for ‘cherry blossom’) was the severe damage to the American battleship West Virginia on April 1, 1945. The first Allied ship to be sunk by an Ohka was the Mannert L. Abele torpedo boat, which was hit off Okinawa on April 12.

Although the majority of these manned missiles missed their targets, the few that did hit wreaked havoc. Especially the carrier aircraft, which the Ohkas had to bring quite close to their targets, proved to be very vulnerable and the powerful American fighter screen therefore never let the Japanese Kamikaze tactics with the flying bomb become a serious threat to the US fleet in the Pacific, despite all its macabre aftertaste.

Altogether 755 Ohka Model 11 of the first production series were built by several manufacturers until March 1945. In addition, there were 45 copies of the version K-1 without engine, which were used for training the pilots.

The Model 22, of which about 50 were delivered, was under-powered. The Model 33, which was not yet finished at the end of the hostilities, was supposed to have Ne-20 turbojet engines of the models 43A and 43B for the launch of submarines or catapults ashore and came too late to see any missions.

Nakajima Ki-115 Tsurugi

Type: Japanese single-seat kamikaze aircraft.

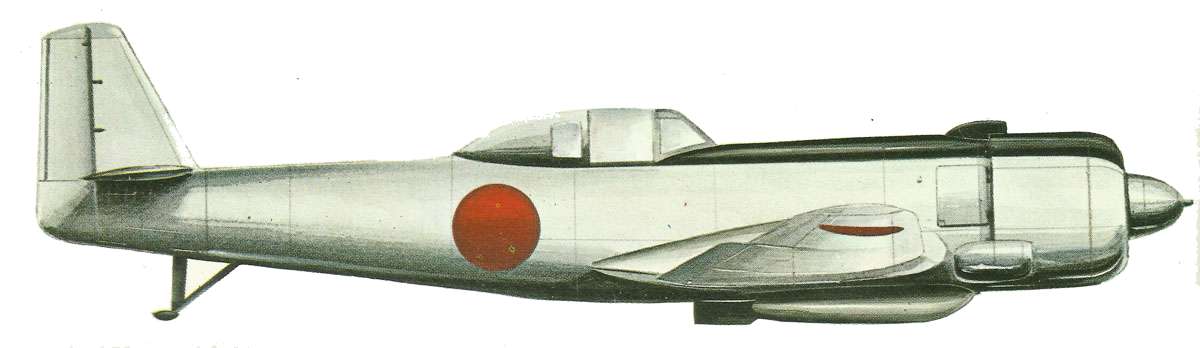

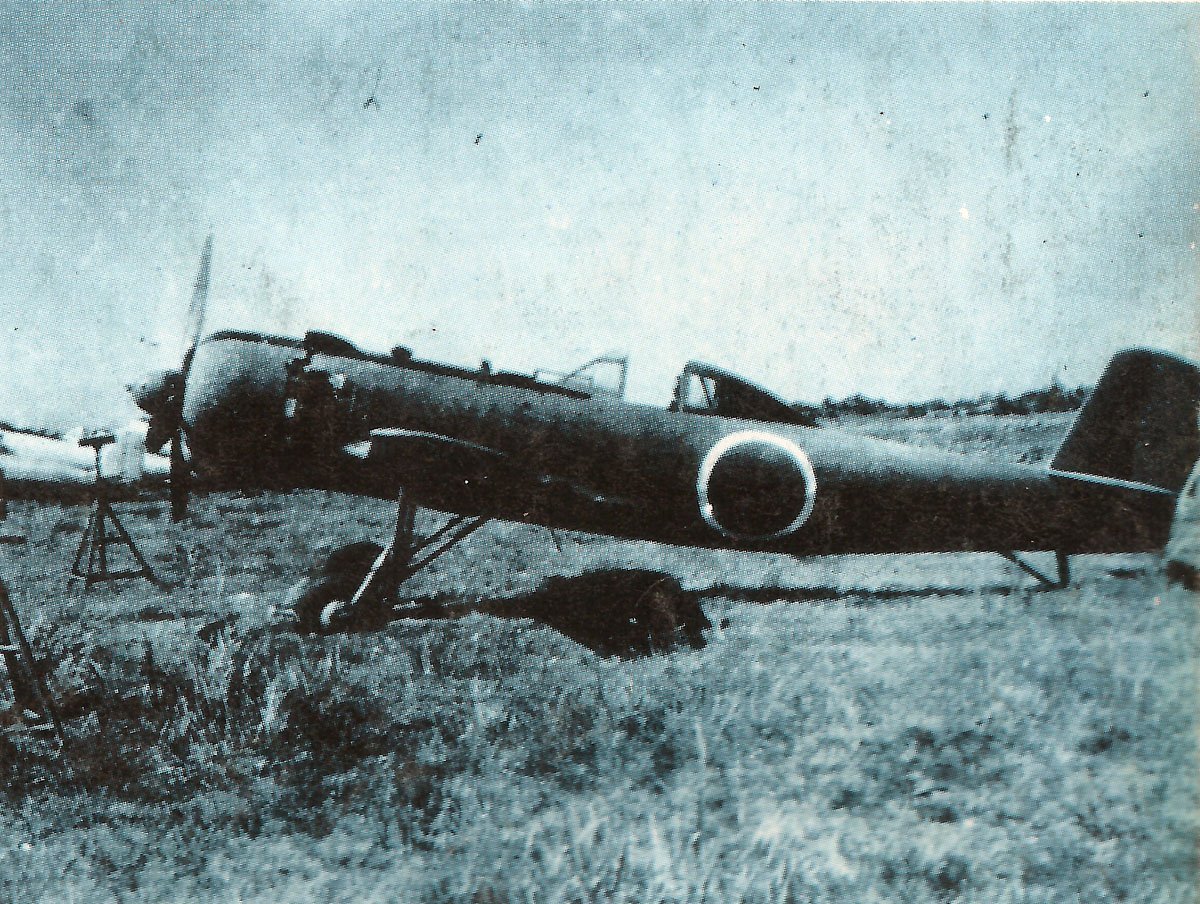

After the operational concept of the Kamikaze pilots and their aircraft had become firmly established in the course of 1944, the Imperial Japanese Army, as well as the Navy, recognized that it was not very efficient to use a colorful collection of unsuitable aircraft models for this purpose. Therefore, an aircraft specially designed for such an attack was to be developed with extreme urgency.

The Nakajima company therefore received the order on January 20, 1945 and the first aircraft was built within three months.

One might have expected that the Ki-115 would be made of cheap wood, but instead the small wing with an all-metal coating, the fuselage was made of steel tubes with surfaces mainly of thin structural steel and the tail unit was made of wood and fabric. The landing gear was made of unsprung steel tubing and was mounted so that it could be dropped after take-off.

The handling of the aircraft was terrible, but improved when a new sprung landing gear and bolted wing flaps were installed.

By the time of the Japanese surrender, Nakajima had only completed 22 of the Kamikaze planes and the Ota Plant had completed 82, all of which were equipped with wing devices for rockets that would never be mounted again to increase speed in the final phase of the attack.

The Ki-115b version was a development with larger wings and a complete wooden fuselage and the ‘Toka’ was a proposal for a naval version. The much more effective Ki-230 was not more built.

Specifications Kamikaze Aircraft

Specifications:

Specifications | Yokosuka MXY7 Ohka | Nakajima Ki-115 Tsurugi |

|---|---|---|

Type | single-seat rocket-powered Kamikaze aircraft | single-seat kamikaze aircraft |

Power plant | three solid-fuel Type 4 Mark 1 Model 20 rockets with total thrust of 1,764 lb (800 kg) | 1.150 PS Nakajima Ha-35 Type 23 14-cylinder radial |

Accommodation | 1 | 1 |

Wing span | 16 ft 9.5 in (5.12 m) | 28 ft 0.5 in (8.55 m) |

Length overall | 19 ft 11 in (6.07 m ) | 28 ft 2.5 in (8.60 m) |

Height overall | 3 ft 10 in (1.16 m) | 10 ft 10 in (3.30 m) |

Wing area | 64.6 sq ft (6.0 m² ) | ? |

Weight empty | 970 lb (440 kg) | 3,616 lb (1,640 kg) |

Weight loaded (maximum) | 4,718 lb (2,140 kg) | 5,688 lb (2,580 kg) |

Max. wing loading | ? | ? |

Max. power loading | ? | ? |

Maximum speed | 290 mph (466 km/h) gliding; 534 mph (860 km/h) max level; 576-621 mph (926-1,000 km/h) final dive | 342 mph (550 km/h) |

Cruising speed | 403 mph (650 km/h) | ? |

Initial climb | - | ? |

Climbing performance | - | ? |

Service ceiling | launched at about 27,000 ft (8,200 m) | ? |

Range | 23-55 miles (37-88 km) | 746 miles (1,200 k) with 1,102 lb (500 kg) bomb |

Armament:

Specification | Yokosuka MXY7 Ohka | Nakajima Ki-115 Tsurugi |

|---|---|---|

forward | - | - |

backward | - | - |

bomb load | warhead containing 2,645 lb (1,200 kg) of tri-nitroaminol | belly recess for bomb of 551 lb (250 kg); 1,102 lb (500 kg) or 1,764 lb (800 kg) |

Service statistics:

Figures | Yokosuka MXY7 Ohka | Nakajima Ki-115 Tsurugi |

|---|---|---|

Development start | August 1944 | 20 January 1945 |

First flight | October 1944 | March 1945 |

Production | early October 1944 | towards the end of the war |

Initial deployment | 21 March 1945 | - |

Final delivery | March 1945 | - |

Price per unit | ? | ? |

Total production figure (all) | 775 | 104 |

Kamikaze pilots

When the Japanese in the final phase of the Pacific War considered the huge differences between their country’s war potential and that of the Allies, it was clear to each of them that the Empire was fast approaching a dangerous crisis unless the situation could be fundamentally changed.

In the tradition of the people of the Japanese Empire at that time, it was only natural for them that the Japanese soldier was determined to sacrifice his life for the emperor and the people. For the Japanese, the entire nation, its society and even the cosmos was a whole through its emperor. This belief was deeply rooted, and they were ready to die for it.

As far as the fundamental question of life and death was concerned, the spiritual attitude of the Japanese was based on absolute obedience to the authority of the emperor, which even extended to the sacrifice of one’s own life.

The kamikaze belief had its origin in ‘Bushido’, the code of honor of the Japanese warrior. This in turn was based on spiritual Buddhism, which influenced courage and conscience.

The convinced Japanese soldier felt the burning desire, if he already had to die, to suffer a meaningful death at the right place and at the right time, without being anxious to receive public recognition.

If you took a closer look at the attitude of the Kamikaze pilots, their mission was simply part of their duty to their country and their emperor and nothing extraordinary. They concentrated solely on how they could hit their target most effectively and destructively and had no thought for their own fate. The dormer was dominated by the ‘life through death’ and so the Kamikaze pilots behaved.

These men gave no insight into their emotional world and were completely influenced by a national attitude and psychological attitude, which had been taught to them by the long history and traditions of Japan.

The Kamikaze attack required first and foremost a mental attitude to the task and any average pilot was suitable for it in terms of his skills. Therefore, there were no special training methods for this, except for teachings on experiences that had proved to be important from previous ‘special missions’.

Since the pilots selected for the Kamikaze attack had mostly just received a hasty pilot training, the Japanese squadron leaders gave them intensive technical training so that they could quickly learn the most important things about it.

Naval Captain Rikihei Inoguchi, who commanded Kamikaze special groups first in the Philippines, then from Formosa and finally was Chief of Staff of the Japanese Air Fleet in the Battle of Okinawa, and whose experiences are reproduced here, gave the following insights into the training program after the war:

On Formosa, the training of Kamikaze pilots took seven days. The first two days were exclusively concerned with taking the aircraft off the runway. This began when the order to deploy was given and continued until all the planes of the formation had gathered in the air.

In the following two days the practice of formation flight followed, together with the technique of launching the machines. The last three days were spent with theoretical and practical training for the approach and final attack on the target. The take-off and formation flight were also practiced.

If the war situation had made it possible, the whole program should have had to be repeated again, according to Inoguchi.

Although an approach at medium altitude would have been ideal for finding and spotting the target, a higher altitude between 19,685 ft (6,000m) and 23,000 ft (7,000 metres) was chosen. At higher altitudes it was more difficult for American fighters to intercept the Japanese attackers and the Kamikaze aircraft loaded with 551 lb (250 kg) bombs were more agile there.

The second possibility was to attack at an extremely low altitude above the water surface to avoid early detection by the Allied radar system. At the end of 1944, the Japanese estimated the effective range of the radar on American warships to be 100 miles (160 kilometres) for high approaching aircraft, 20 to 30 miles (32 to 48 kilometres) at medium altitudes and 10 miles (16 kilometres) for low approaching aircraft.

When enough Kamikaze aircraft were ready for action, the attack was carried out simultaneously from different directions from one formation in low-flying and one in high-flying.

During an approach from high altitude, the kamikaze pilot had to make sure that the angle of descent during the attack was not too large, otherwise the aircraft was difficult to control and could get out of control as the speed increased.

Therefore, it was important that the pilots learned to set the nosedive as flat as possible, taking into account the wind as well as possible evasive maneuvers of the target.

When approaching the target in low level flight, the Kamikaze pilot, after recognizing the enemy fleet, climbed steeply upwards until he reached 13,100 to 16,400 ft (4000 to 5000 meters) before he threw himself onto a ship at a steep angle. However, this procedure required a high level of skill on the part of the pilot, but the Japanese had found in their previous attacks that a hit on the deck of the attacked ship was considerably more effective than into the side.

The Kamikaze pilots were therefore encouraged to use this method when their skill was sufficient and the conditions of the attack allowed it.

For this reason, the training to become a Kamikaze pilot, despite its brevity, was very hard and included getting into the aircraft, take-off, formation flying and the actual attack.

When taking off with their heavily loaded aircraft the Kamikaze pilot was not allowed to climb too fast, had to operate the controls carefully and retract the landing gear at a constant altitude of about 100 ft (30 meters).

After take-off, it was important for the pilot to catch up with the formation and to keep as little distance as possible to the other aircraft so that the group did not have to fly a large arc when changing direction.

The most important target of the Kamikaze pilots were of course the American aircraft carriers. The most effective area for a hit was the middle elevator and the next most favorable area was the front or rear elevator.

With other, larger warships the best target was the beginning of the bridge construction. For destroyers, smaller warships and transporters, the Kamikaze aircraft should hit somewhere between the bridge structure and midships.

Theoretically four Kamikaze planes should have been used against an aircraft carrier. Two of them should have hit the middle one and one each the front and rear elevator. Two or three Kamikaze planes each were to be secured by an escort fighter.

However, the lack of their own aircraft and the large number of Allied aircraft carriers forced the Japanese to use mostly only one Kamikaze aircraft against each aircraft carrier.

References and literature

Combat Aircraft of World War II (Bill Gunston)

Technik und Einsatz der Kampfflugzeuge vom 1. Weltkrieg bis heute (Ian Parsons)

Das große Buch der Luftkämpfe (Ian Parsons)

Luftkrieg (Piekalkiewicz)

Flugzeuge des 2. Weltkrieges (Andrew Kershaw)

World Aircraft World War II (Enzo Angelucci, Paolo Matricardi)

Flotten des 2. Weltkrieges (Antony Preston)

Seemacht – eine Seekriegsgeschichte von der Antike bis zur Gegenwart (Elmar B. Potter, Admiral Chester W.Nimitz)

The Encyclopedia of Weapons of World War II (Chris Bishop)