The anti-Semitism, persecution and deportation of Jews until the final solution ‘Holocaust’ in the Third Reich.

The unique decision to murder the Jews was taken by Hitler in 1941 under specific circumstances. It was an absolute state secret that not even insiders were allowed to talk about.

The decisive instructions were obviously all given only orally as ‘the Führer’s wish’ and the entire initiated leadership used only camouflage expressions. Hitler himself never spoke about murdering the Jews, not even in the closest private circle.

SS chief Heinrich Himmler, on the other hand, who fulfilled Hitler’s ‘wishes’, spoke openly about it at least twice from October 1943, probably already anticipating defeat and knowing that he had already burned all bridges behind him.

Therefore, the sequence of events leading to the Holocaust can only be reconstructed with circumstantial evidence. Also, there was probably not such a thing as a day of decision, rather it is a progressive development, which between the ‘wishes’ of the Nazi leadership and the measures by sub-leaders on the ground mutually swung up.

Written orders for the Holocaust were never found, and the files which Himmler and Heydrich must have created in the course of the war were obviously destroyed in time before the collapse. But the ‘Final Solution of the Jewish Question’ clearly bears Hitler’s signature.

Antisemitism

Table of Contents

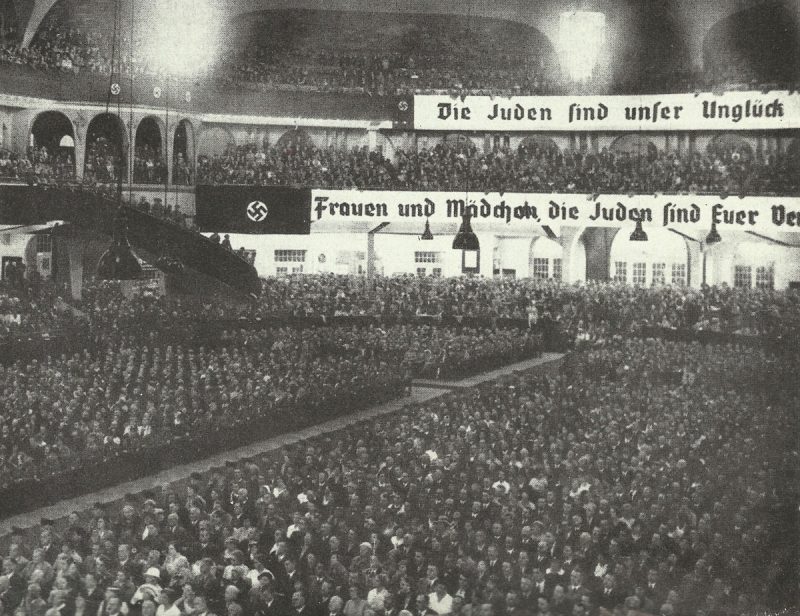

Before the Holocaust, there was a long history of anti-Semitism in many parts of Europe: in Spain, France, Poland, Ukraine and Russia, as well as in the Middle East. In the Russian Empire and Eastern Europe in particular, hatred of Jews had traditionally been pronounced and stood out for brutal ‘pogroms’ in which Jews were murdered locally. The word ‘pogrom’ also comes from Russian.

But anti-Semitism also occurred in Western Europe, with the Dreyfus affair rocking France before World War One.

Until that time, Germany was not necessarily an anti-Semitic hot spot, and the small Jewish population saw itself as fully assimilated and participating in German culture. However, since many of their members were wealthy, there was envy and numerous anti-Semitic writings appeared as early as Bismarck’s time.

Nevertheless, anti-Semitism was not strong in Germany, and the state policies of imperial Germany stood in the way. Only with Germany’s defeat in World War I and the Bolshevik Revolution in Russia were culprits sought, and they were quickly found in the Jews.

Hitler himself, already a convinced anti-Semite from his Vienna days, enthusiastically took up these ideas for his new Nazi party, the NSDAP.

Nevertheless, Jews were relatively safe in the pluralistic Weimar period until 1929 and also felt ‘at home’, but found few friends except in liberal and leftist circles and were exposed to agitation and discrimination.

With Hitler’s seizure of power on January 30, 1933, however, their situation changed abruptly, although the increasing radicalization up to 1938 was largely not due to direct orders from Hitler and was driven primarily by anti-Semitic fellow travelers and party comrades. Hitler was actively involved only in the Nuremberg Laws of 1935 and presumably in the November pogrom of 1938. He later explained his relative inaction by saying that he had to exercise restraint for foreign policy reasons and not because this was what he wanted.

Persecution of Jews

Despite intense harassment of Jews to induce them to emigrate, two-thirds of the 1933 Jewish population still lived in Germany at the end of 1938.

The phase of serious persecution of Jews by the Nazis began a few days after the Munich Conference in October 1938, and the trigger was, of all things, the Polish government. The latter issued a decree according to which every Polish citizen living abroad had to return to his homeland within three weeks in order to have his passport stamped with a special stamp. All Poles who had not done so by October 29, 1938, would automatically lose their Polish citizenship.

The goal of the unusual measure was quickly clear, because the largest group of Polish citizens abroad – except for the USA – lived in Germany and consisted mostly of Jews. Poland wanted to get rid of the approximately 60,000 Jews living in Germany once and for all.

Therefore, before the deadline expired, SD chief Heydrich brought Jews of Polish nationality to the German-Polish border by railroads, buses and trucks. Nevertheless, the Poles closed the border at many points to Polish citizens who had returned to register their passports.

Of the approximately 17,000 Poles waiting at the border on the evening of October 28, the majority must spend the cold and damp night in no man’s land.

Among the people who suffered at the border is the family of a shoemaker named Grynszpan, Germanized sometimes called as Grünspan. Herschel Feibel Grynszpan was 17 years old at the time and lived in Paris, where he learned of his family’s fate.

On the morning of November 7, 1938, the young man visited the German embassy in Paris and wanted to speak to the ambassador. Of course, the unknown man was not let in, but the third secretary of the embassy, Ernst von Rath, also a young man from a family little inclined to the Nazis, took care of him. Herschel Grynszpan immediately shot the young official with a revolver, and then testified to the French police that he had done so in revenge for his family on the Polish border.

However, it was later believed that Grynszpan had a homosexual relationship with the embassy secretary and that the act was done out of relationship problems and not for political reasons.

Be that as it may, it was now too late for that, for the murder of the German embassy secretary by a Jew had radical consequences.

Two days later, at Hitler’s annual celebration of the march to the Feldherrnhalle, it was announced over dinner in Munich’s City Hall that Ernst von Rath had just succumbed to his serious injuries in Paris.

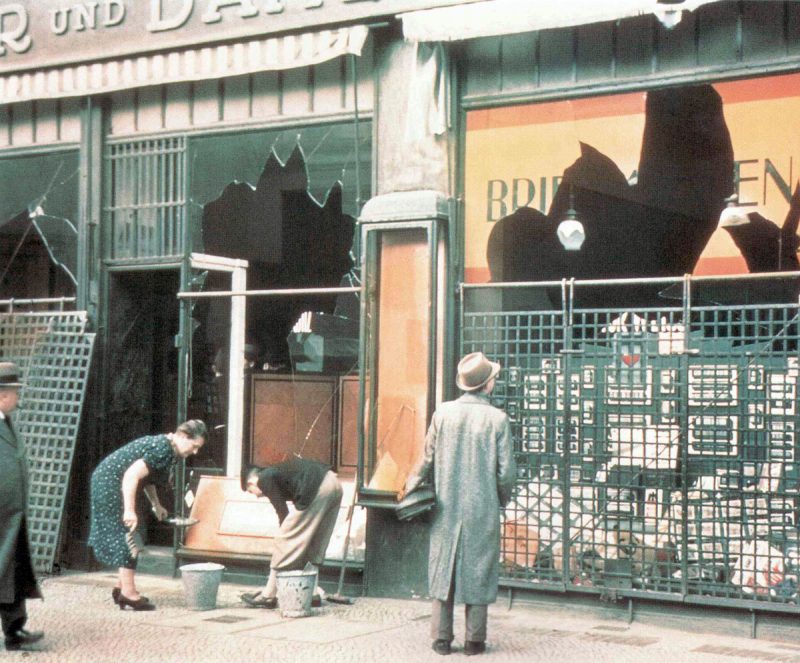

Who now ordered the following ‘Reichs-Kristallnacht’ (‘Night of broken glass’) is unknown until today. Hitler, in any case, rejected this in his later table talks, since this had severely damaged him in terms of foreign policy.

It was more likely a spontaneous action by lower party henchmen who had been incited by Goebbels’ inspired anti-Jewish press reports of the assassination.

In any case, shortly after midnight, Gestapo chief Heinrich Müller sent a telex to all state police departments announcing actions against Jews and synagogues throughout Germany in the shortest possible time that were not to be disturbed. Looting and excessive rioting were to be prevented and some 20,000 to 30,000 Jews were to be imprisoned. The direction of the actions was to be the responsibility of the ‘Stapo’ (state police).

The terror of the ‘Reichs-Kristallnacht’ now actually triggered a wave of flight and between the end of 1938 and the beginning of the war in 1939, as many Jews left Germany as in all the years of Nazi rule before. But even shortly after that night, SD chief Heydrich still believed it would take a decade to get rid of all the Jews.

After the riots ‘Reichs-Kristallnacht’ had met with considerable criticism abroad and also in Germany itself, public outbursts of violence were now avoided by the Nazis. Therefore, on January 24, 1939, Heydrich was appointed head of a Reich center for Jewish emigration.

In the meantime, however, Poland has already taken initiatives to get rid of its Jewish minority. In fact, the new ‘Madagascar Plan’ originated in Poland, which sought bilateral talks with France to establish a Jewish state off the East African coast. Palestine was out of the question at that time, since the land had already been settled by the Arabs for two thousand years and they would then have had to be expelled.

But a Jewish state on Madagascar also seemed interesting to the French, since its area was twice as large as Poland, but it had only four million inhabitants. The fourth largest island in the world is rich in mineral resources and natural wealth, and the well-known Jewish business activity could lead to flourishing and prosperity there.

Until the beginning of the war, however, this was only negotiated theoretically and the whole thing only became half serious when, a year and a half later, German authorities negotiated with the then defeated France.

In Germany, until the outbreak of war in September 1939, the first thing to do was to make a business out of the forced emigration of Jews abroad, which now had to open its borders for them willy-nilly after the ‘Reichs-Kristallnacht’.

From November 1938 to January 1939, Jewish citizens were deprived of pretty much all their rights, denied attendance at public schools and banned from working.

Deportations and ghettos

After the outbreak of the Second World War and as soon as the Polish campaign was over, the conquered country became a training area for a ‘final solution’.

For the first time, non-Germans formed the majority in territories annexed by Nazi Germany, and in addition to the German minority there was also a large minority of Jews, which was now added to the ‘problem’ of the Reich German Jews.

The territories claimed by Germany in Poland were to be Germanized as soon as possible, but getting rid of the Poles there would take longer. The Jews, however, were to be dealt with differently, and so the Gauleiter of what was to become Wartheland announced as early as November 1939 that the ‘Jewish question’ would soon be solved.

The first idea was to create a huge reservation between the Vistula and the Bug for Jews from the annexed territories and also from Germany, as well as for 30,000 Sinti and Roma.

Heydrich assumed that the action would take a year, but already went beyond mere ‘evacuation’. Thus, thousands of Polish Jews had already been killed by mass shootings or in Polish pogroms by this time. The deportation of Jews to the Lublin district also ‘decimated’ the Jewish population, which was not inconvenient.

A short time later, however, the Governor General Hans Frank declared that the planned deportations to the areas east of the Vistula were completely impossible, since the Generalgouvernement was already overpopulated and impoverished anyway and also did not have enough food.

Then, in the spring of 1940, it was clear to the responsible persons that the planned resettlement of huge populations to the east in the previous German sphere of power was completely unrealistic. Thus, ghettos became permanent institutions, although they were originally intended only as a kind of transitional camp before deportation to the East.

In the meantime, Governor General Hans Frank had again initiated the old idea, first put forward by Paul de Lagarde at the end of the 19th century, of resettling Jews in the French colony of Madagascar.

After the victorious Western campaign, the idea no longer seemed entirely outlandish, and the enterprising Reichsmarschall Göring exulted that the Jews could build up a flourishing trading economy on the island under German supervision and that Germany would share in the expected profits.

One single but crucial problem, however, could not be eliminated: Britain was still at war with Germany and controlled the sea routes, so that deportation by ship was completely impossible as long as there was no peace.

However, Hitler’s decision to attack the Soviet Union in the coming year 1941 opened up completely new perspectives for the ‘solution of the Jewish question’.

References and literature

Illustrierte Geschichte des Dritte Reiches (Kurt Zentner)

Fateful Choices (Ian Kershaw)

Unser Jahrhundert im Bild (Bertelsmann Lesering)

Hitlers Tischgespräche im Führerhauptquartier (Henry Picker); in English: Hitler’s Table Talk