The Russian Army of the Tsar in World War One from August 1, 1914, to December 15, 1917.

Uniforms, organization, leaders, organization and casualties.

The Russian Army 1914-17

Table of Contents

The Russian Army in **World War I (1914–1918)** was one of the largest military forces in the conflict, but it faced enormous challenges that ultimately contributed to the collapse of the Russian Empire.

Overview

Size and Mobilization

– At the outbreak of war in 1914, Russia had the largest standing army in Europe, with around 1.4 million soldiers.

– Through mobilization, this number swelled to over 12 million men over the course of the war.

– Despite its size, the army was poorly equipped compared to Germany and Austria-Hungary. Many soldiers lacked rifles, artillery shells, and even basic supplies.

Early Campaigns

– Russia launched offensives against both Germany (East Prussia) and Austria-Hungary (Galicia) in 1914.

– The Battle of Tannenberg (August 1914) was a disastrous defeat against Germany, where the Russian Second Army was encircled and destroyed.

– However, Russia had more success against Austria-Hungary, winning early victories in Galicia.

Challenges

– Logistics: Russia’s vast distances and underdeveloped rail network made supplying troops difficult.

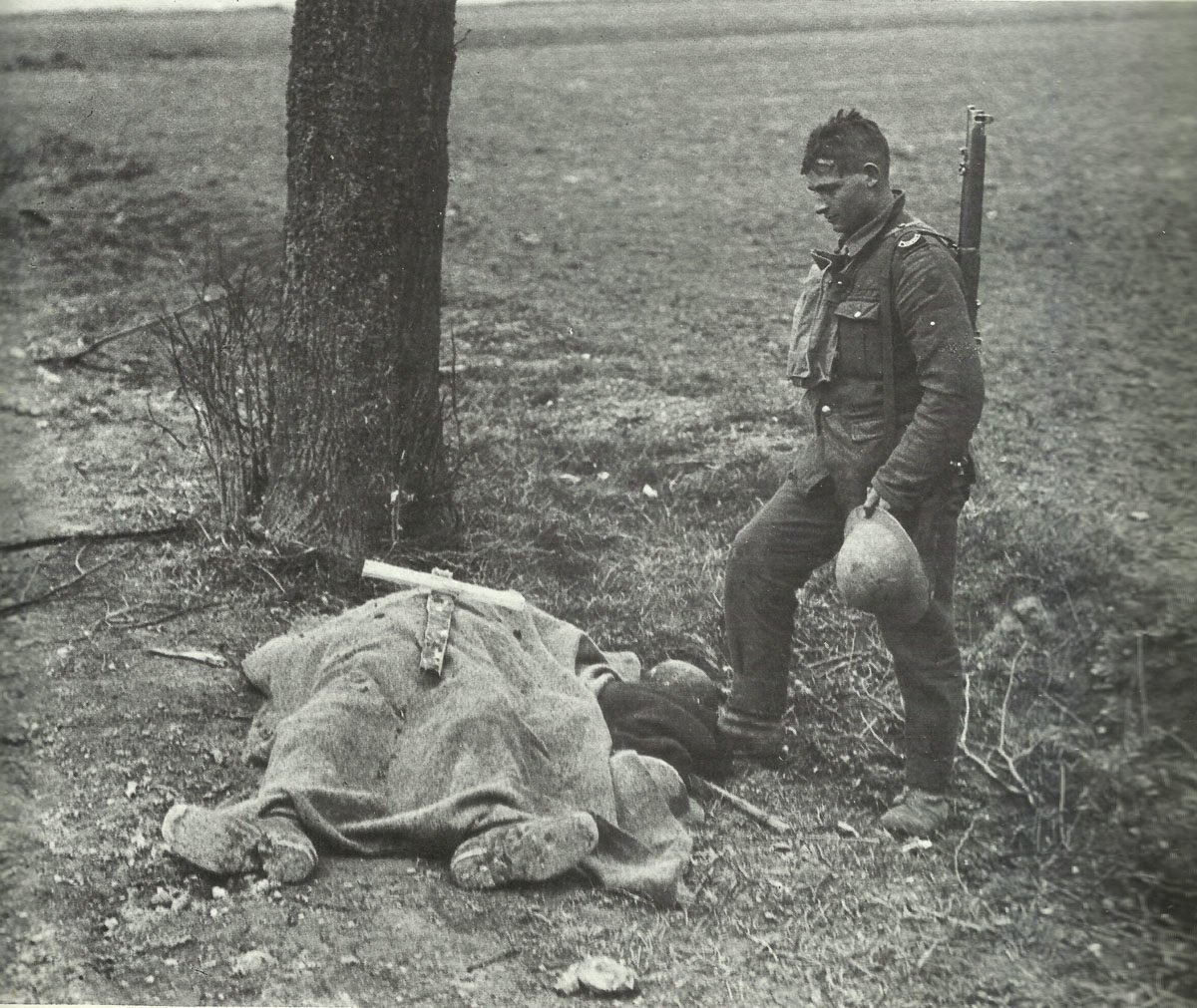

– Equipment Shortages: At times, soldiers were sent into battle without rifles, ordered to pick up weapons from fallen comrades.

– Leadership: The officer corps was often dominated by aristocrats, with varying levels of competence.

– Morale: Heavy casualties and poor conditions led to declining morale and desertions.

Major Campaigns

– 1915: Germany launched the Gorlice–Tarnów Offensive, forcing a massive Russian retreat from Poland and causing huge losses.

– 1916: The Brusilov Offensive against Austria-Hungary was Russia’s most successful operation, inflicting massive casualties on the Austro-Hungarian army. However, it also drained Russian manpower.

– 1917: The army was demoralized by food shortages, political unrest, and revolutionary propaganda. The Kerensky Offensive (July 1917) collapsed quickly, showing the army’s disintegration.

Collapse and Revolution

– By late 1917, discipline had broken down. Soldiers mutinied, deserted, or joined revolutionary movements.

– After the Bolshevik Revolution (November 1917), Russia signed the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk (March 1918) with Germany, officially withdrawing from the war.

Impact

– Russia’s poor performance undermined confidence in the Tsarist regime.

– The strain of the war was a major factor in the Russian Revolution of 1917.

– Millions of Russian soldiers and civilians died, making it one of the most devastating experiences in Russian history.

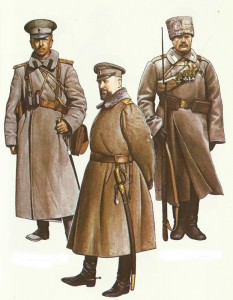

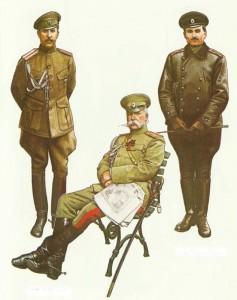

Russian Army at the beginning of World War One

Russia had fought Japan in Manchuria in 1904-05 and been badly worsted. Since then efforts had been made with the aid of large loans from France to modernize the army, but the combination of vast numbers and restricted resources had prevented it reaching the standard of Western armies of the day. In such choice as there was between quantity and quality, Russia had chosen quantity, instinctively believing that sheer numbers would bring victory. While a Russian division had sixteen battalions against a German division’s twelve, its fighting power was only about half that of the German.

The peace strength of the Russian army was 1,4230,000 men. On mobilization, three million men were called up at once, with 3,500,000 men more to follow before the end of November 1914. There were thirty-seven corps, mostly of two divisions, and in all seventy first-line divisions, nineteen independent brigades, thirty-five reserve divisions, twenty-four cavalry and Cossack divisions with twelve reserve.

It was planned to deploy thirty corps – ninety-five infantry and thirty-seven cavalry divisions, some 2,700,000 men – against Germany and Austria, but of these only fifty-two divisions could appear by the twenty-third day of mobilization (22nd August 1914). Two armies, the 1st and 2nd, would face East Prussia; three, the 5th, 3rd and 8th, Austria. Another, the 4th, would deploy against Germany (Plan G), if the main German strength came east, or against Austria (Plan A), if it struck west against France. Two more armies watched the Baltic and Caucasian flanks. General mobilization was ordered on 29th July 1914, and on 6th August, deployment on Plan A.

General Sukhomlinov, minister for war since 1909, had been an energetic reorganizer, backed by the Tsar; he was corrupt, possibly pro-German, and a military reactionary, boasting that he had not read a manual for twenty-five years.

Grand Duke Nicholas, commander-in-chief, fifty-eight, an imposing figure six-foot-six tall, was a champion of reform and opposed by Sukhomlinov. The jealousy of his nephew, the Tsar, had kept him from the Russo-Japanese War, depriving him of the chance to prove his worth as a commander, but also keeping him free of blame for the defeat.

General Zhilinsky, commanding against East Prussia, had visited France in 1912 when chief of general staff, and had absorbed Foch’s military beliefs, while also becoming personally committed to Russia’s undertaking for an early advance against Germany.

Almost from the moment of declaration of war, France began to urge Russia to make this advance quickly and in strength. Russia responded gallantly, sacrificing her chance of massive deployment before action. Perhaps it needs hardly be added that in Russia, as elsewhere, progressives and reactionaries were agreed on one thing, their faith in the offensive.

RUSSIA (August 1, 1914 – December 15, 1917)

- Soldiers available on mobilization = c.4,500,000

- Army strength during the war = 15,000,070

- KIA Military = 1,700,000

- Wounded Military = 4,950,000

- Civilian losses = 2,000,000+

References and literature

History of World War I (AJP Taylos, S.L. Mayer)

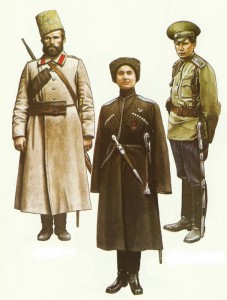

Army Uniforms of World War I (Andrew Mollo, Pierre Turner)