The Last Japanese Soldiers to Surrender After the Second World War: A Historical Overview.

The Japanese soldiers who continued to fight for years after Japan’s surrender

Table of Contents

After World War II ended in 1945, not all soldiers were quick to lay down their arms. Remarkably, some Japanese soldiers continued to fight for years, refusing to believe the war was over. These soldiers were known as holdouts, and they became symbols of unwavering loyalty to their cause.

One of the most famous cases was Hiroo Onoda, a second lieutenant who held his position in the Philippines until 1974. His dedication became legendary, as he survived for almost three decades in jungles, carrying out guerrilla warfare and living off the land. Even after being declared dead in 1959, he persisted until a direct order from his former commander convinced him that peace had long been declared.

These incredible stories of survival and devotion capture both the complexity and the tragedy of war. They reflect the powerful mindset of soldiers who committed their lives to their duties despite the changing world around them, offering a unique perspective on history and human endurance.

Historical Context of Japanese Holdouts

After World War II ended, some Japanese soldiers continued to fight, driven by loyalty and military discipline. Their actions were influenced by Japan’s strict surrender policies and the disconnect with the rapid changes under Allied occupation in post-war Japan.

The Concept of Japanese Stragglers

Japanese stragglers were soldiers who continued military activities after Japan surrendered in 1945. These holdouts were often isolated in the jungles of the Pacific islands. They remained hidden due to lack of communication and disbelief in Japan’s defeat. The stragglers were steadfast in their loyalty to their emperor and country, often waiting for direct orders to cease.

Many stragglers were influenced by Allied propaganda, which they perceived as deceptive. This reinforced their reluctance to surrender. The idea of being captured was also seen as deeply shameful, a significant cultural barrier to giving up arms.

Imperial Japanese Army’s Surrender Policies

The Imperial Japanese Army’s surrender policies were rooted in a strong code of honor. Soldiers were taught never to surrender and to fight to the death. These policies made it difficult for soldiers to accept defeat, especially in isolated locations where news traveled slowly.

Leadership figures like General Tomoyuki Yamashita influenced soldiers with his uncompromising spirit. Yamashita’s military command often emphasized resilience, which persisted among troops unfamiliar with Japan’s surrender. This mindset sent a ripple through Japanese forces, creating a legacy where soldiers held out for decades, waiting for an unlikely victory or command.

Allied Occupation and Post-War Japan

The Allied occupation of Japan drastically altered the country. Allied forces, led mainly by the United States, imposed reforms and disbanded the Japanese military. This shift left some soldiers stranded and unaware of these changes.

During this period, Japan rebuilt its identity under new political and social systems. The intervention of Allied occupying forces was both a period of reconstruction and intense cultural transformation. Those who remained in the jungles isolated from this change retained their outdated beliefs and wartime duties, highlighting the stark contrast between post-war Japan and holdout experiences.

Prominent Figures Among the Holdouts

The end of World War II didn’t reach all Japanese soldiers. Among these holdouts, some continued their missions without knowing the war had ended. Their stories include enduring isolation, loyalty, and eventual return to society.

Lieutenant Hiroo Onoda’s Odyssey

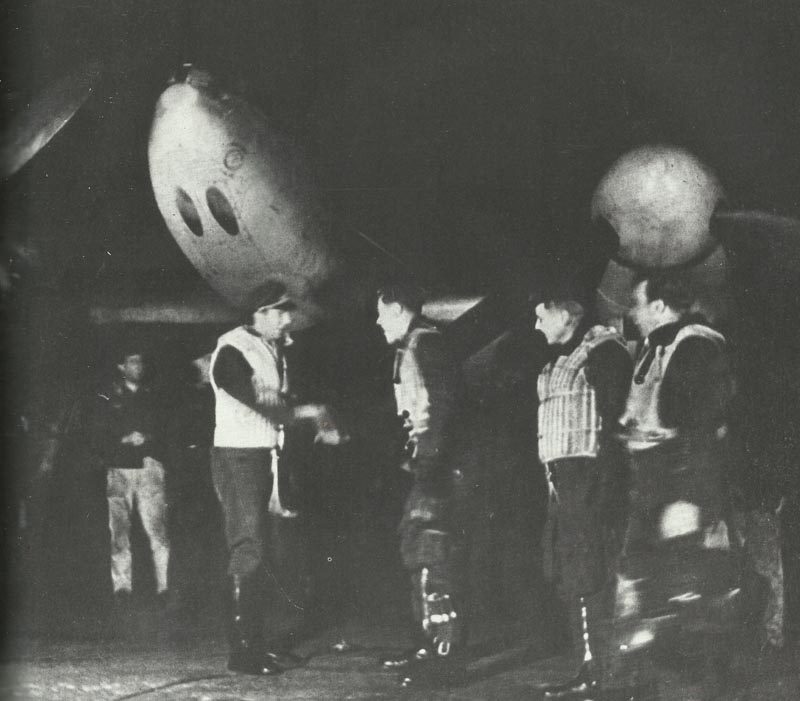

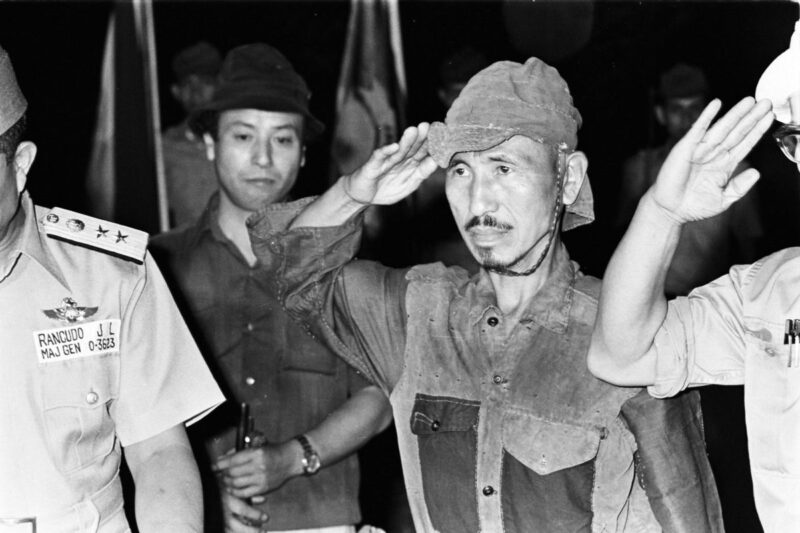

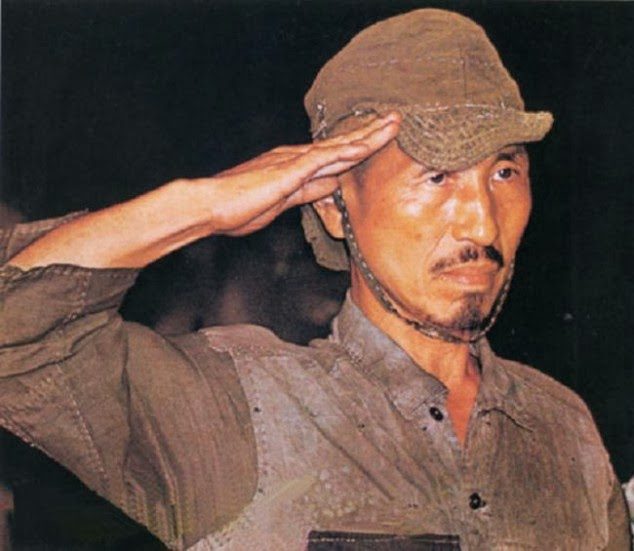

Hiroo Onoda, an intelligence officer, was ordered to Lubang Island in the Philippines in 1944. His mission was to gather intelligence and conduct guerrilla activities. Despite Japan’s surrender in 1945, Onoda held out until 1974.

Onoda lived in the jungle with a small group, maintaining their war stance. They relied on local resources and practiced extreme survival tactics. His loyal companion, Kinshichi Kozuka, continued with him until Kozuka was killed in 1972.

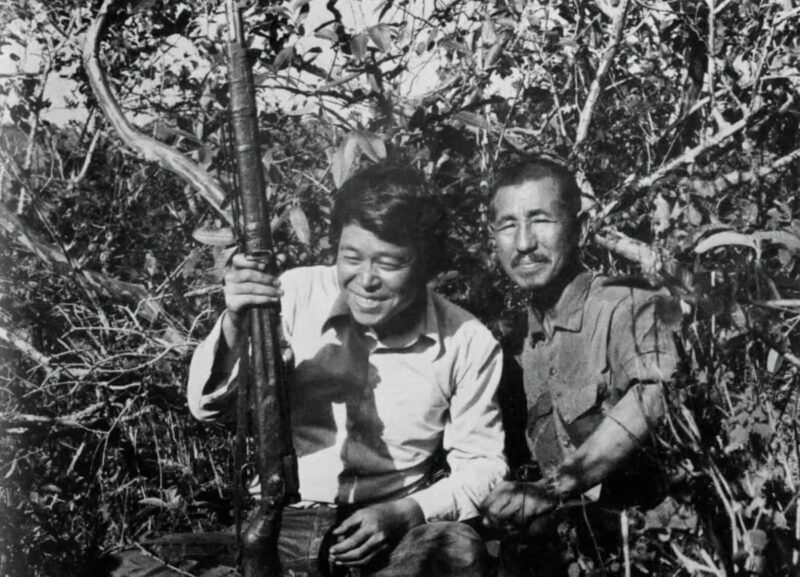

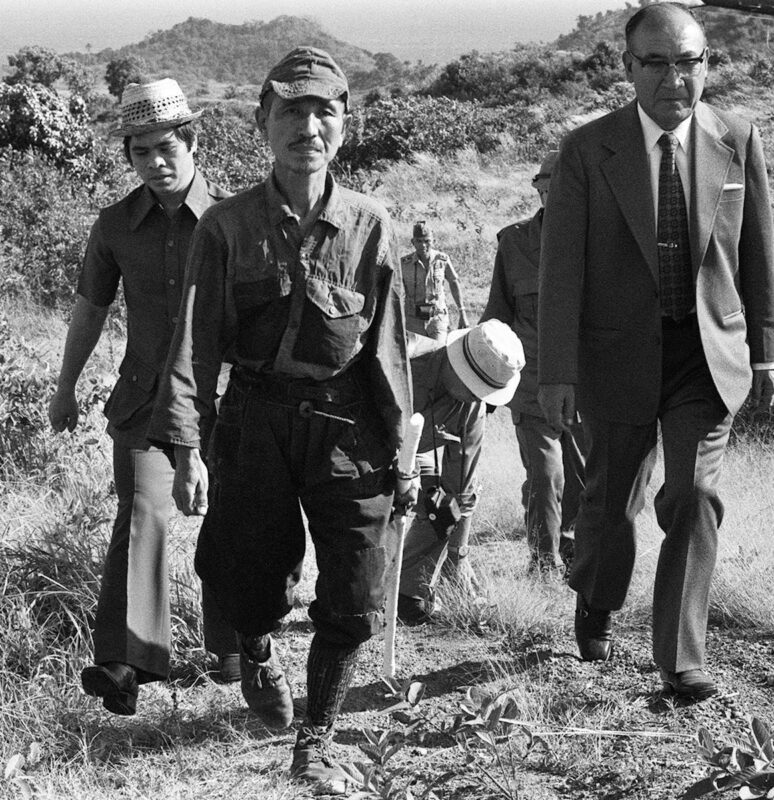

His perseverance only ended after meeting adventurer Norio Suzuki. Suzuki traveled to find Onoda and finally convinced him the war was over. Major Yoshimi Taniguchi, his former commanding officer, formally relieved him of duty, ending his nearly 30-year odyssey.

Sergeant Shoichi Yokoi on Guam

Shoichi Yokoi was a soldier stationed on Guam during World War II. When American forces captured the island, Yokoi chose to hide instead of surrendering. He stayed concealed in the dense jungles for nearly 28 years, until he was discovered in 1972.

Yokoi survived by hunting and gathering and made clothing from natural fibers. He hid in a cave, trying to avoid detection while refusing to believe the war had ended.

Even when discovered by local hunters, he remained cautious and suspicious. He was the last of three soldiers who initially hid together, as his companions emerged earlier.

Upon his return to Japan, Yokoi expressed regret for his lengthy absence. His story became one of resilience, heavily shaping perspectives on loyalty and endurance.

Private Teruo Nakamura’s Seclusion

Teruo Nakamura, originally from Taiwan, served in the Japanese army during the war. He was stationed on Morotai Island, Indonesia. Unlike other holdouts, his background as a Taiwanese aborigine meant he had fewer cultural ties to Japan.

Nakamura lived in solitude for almost 30 years, unaware the war had concluded. It wasn’t until 1974 that Indonesian authorities found and convinced him to return to society.

Living in seclusion, Nakamura constructed a modest settlement where he fended for himself. His discovery marked the last official holdout, representing a complex tale of identity and survival.

With his return to Taiwan, he received little acknowledgment, partly due to its unique cultural status as a Japanese collaborator. His life in Japan ended quietly, yet his story remains a poignant chapter in the history of those who stayed lost after the war.

Significant Locations of Japanese Holdouts

Japanese holdouts stayed hidden in various remote areas long after World War II ended. These locations, such as Lubang Island and the vast jungles of Guam, became significant for those unwilling to surrender.

Lubang Island: Onoda’s Hideout

Lubang Island in the Philippines became famous due to Hiroo Onoda. He continued his mission for nearly 30 years, unaware the war had ended. The dense jungle provided Onoda with the cover he needed to remain hidden.

During this period, he performed raids and avoided capture. It wasn’t until a search led by Norio Suzuki found him in 1974 that Onoda finally accepted the war was over. This marked one of the last significant surrenders of a Japanese soldier.

The Dense Jungles of Guam and Philippines

Guam’s jungles also held hidden soldiers. Shoichi Yokoi spent 27 years living in the tropical wilderness. He used his survival skills to evade detection from locals and military personnel.

The Philippines was another region where Japanese soldiers, including those on Luzon and other islands, maintained positions. Dense forestry, challenging terrain, and cultural isolation allowed them to remain unseen until their eventual discovery and surrender decades later.

Isolated Islands of the Pacific

Numerous Pacific islands, like Morotai and Guadalcanal, became hideout sites for Japanese soldiers. Anatahan Island saw several holdouts before they were discovered and brought back in the early 1950s.

Islands like Peleliu and Vella Lavella had soldiers holding out due to their physical isolation. These soldiers relied on what remained from war provisions or whatever they could find to survive. Each location tells a story of isolation, survival, and long-delayed acceptance of war’s end.

Shocking discovery in 2005: Japanese soldiers from the Second World War found alive in the Philippine jungle

Two elderly Japanese men, believed to be former World War II soldiers, have been discovered in the jungles of Mindanao (Philippines). This remarkable find comes almost 60 years after the end of the Second World War and is reminiscent of the famous case of Lieutenant Hiroo Onoda, who was found in 1974.

The two men, both aged over 80, were reportedly found on the southern island of Mindanao and are believed to have been living with local Muslim rebel groups. At least one of them had married a local woman and started a family.

Presumably, the men were most likely members of the Panther Division, 80% of whom were killed or went missing in the last months of the war.

It has been speculated that up to 40 Japanese soldiers could still be living in similar conditions in the Philippines at the beginning of the millennium.

Survival and Resistance Tactics

Japanese holdouts like Hiroo Onoda and Teruo Nakamura used various strategies to continue their fight after World War II ended. These tactics included guerrilla warfare, adapting to their challenging environments, and continuing their duties while evading capture.

Guerrilla Warfare and Intelligence Gathering

The holdouts often engaged in guerrilla warfare, relying on their military training. They used the dense jungle landscape to their advantage, launching surprise attacks and retreating quickly. This form of warfare was well-suited to their situation, as it allowed small groups to challenge larger forces effectively.

In addition to combat skills, intelligence gathering was crucial. They gathered information from limited interactions with locals, carefully observing any activities around them. This cautious approach helped them avoid traps set by local police or military efforts to capture them.

Adapting to Harsh Environments

Stragglers and holdouts had to adapt quickly to survive in harsh jungle conditions. They built shelters from available materials, often living in small huts that could be easily hidden from view. Survival depended on utilizing resources like rainwater and native plants for food and medicinal needs.

Their training as soldiers helped them endure these conditions, but resourcefulness was key. Lacking regular food supplies, they sometimes raided cattle ranches for protein, all while maintaining a low profile to avoid attracting attention.

Avoiding Capture and Continuation of Duties

Avoiding capture was a constant challenge for these holdouts. They altered their routines to confuse those looking for them and stayed hidden for long periods. The isolated environment was both a safe haven and a source of threat, as any interaction could lead to discovery.

Despite being cut off, they continued to perform military duties. This dedication was reflected in their maintenance of weapons and uniforms, often keeping these in good condition even after many years. Their loyalty to orders, received decades earlier, fueled their ongoing resistance, making their surrender stories both remarkable and poignant.

Surrender and Repatriation

In the aftermath of World War II, several Japanese soldiers continued to hold out in remote locations, refusing to accept the war’s end. Their eventual surrender and repatriation offer a unique lens on Japanese post-war history, culture, and society.

Final Encounters and Official Surrender

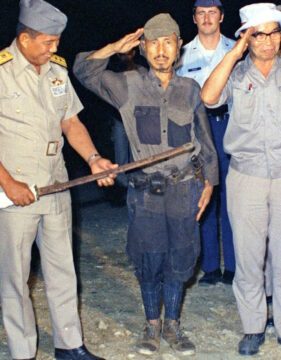

Multiple soldiers from Japan resisted surrender for years. Shoichi Yokoi and Hiroo Onoda are among the most famous. Yokoi emerged from the jungles of Guam in January 1972, while Onoda held out in the Philippine jungle until March 1974. Onoda only surrendered after his former commander traveled to inform him that the war had ended. The formal surrender ceremonies were significant, often involving military personnel and local officials. These soldiers were ultimately persuaded that the conflict had ended.

Return to Japan and Reception

Upon their return to Japan, these soldiers were met with mixed feelings. Hiroo Onoda received a hero’s welcome from some quarters and met with Philippine President Ferdinand Marcos in a formal ceremony. Others experienced a more modest reception. Their repatriation became symbolic, reflecting the end of Japan’s post-war period and its efforts to rebuild. For many, this return was accompanied by media attention and public fascination. Their stories captivated the nation, highlighting a dedication to duty that resonated with aspects of Japanese values.

Assimilation and Impact on Modern Japanese Society

These soldiers faced challenges adjusting to modern Japan. After years of isolation, they had to find their place in a society vastly different from the one they had left. For some, this transition was eased through public speaking, memoirs, and involvement in educational programs, like the Onoda Nature School. Their stories have shaped cultural narratives around perseverance and loyalty. The conversation around their actions continues to influence contemporary discussions within Japan about militarism, national identity, and the impact of war. This complex legacy highlights tensions between traditional Japanese values and modern societal dynamics.

Cultural and Historical Legacy

Japanese soldiers who continued their fight long after World War II’s official end provide unique insights into the cultural mindset of the time. Their stories reveal lasting impacts in literature, film, and public memory, reflecting ongoing themes of duty and nationalism. Educational narratives use their experiences to discuss history and the formation of identity.

Literature and Film Depictions

Hiroo Onoda’s story has inspired numerous books and films, spotlighting his unwavering dedication. “No Surrender: My Thirty-Year War” is his autobiography, providing personal insight into his beliefs and experiences. Films like “Onoda: 10,000 Nights in the Jungle” further explore his incredible survival in the Philippines, combining historical fact with dramatization.

Shoichi Yokoi and Teruo Nakamura also feature in various media, drawing attention to different perspectives on similar experiences. These works serve as reminders of the complexities of war and its aftermath, capturing the human element behind military decisions.

Militarism and Nationalism in Contemporary Japan

The stories of Japanese holdouts are often used in discussions about militarism and nationalism in modern Japan. Onoda and others were trained at the Nakano School and held deep-seated beliefs taught to soldiers of imperial Japan. Their persistence is sometimes seen as extreme yet reflects a historical context of unwavering loyalty.

These narratives influence contemporary debates about Japan’s military past and present, affecting how Japan sees itself on the world stage post-Pearl Harbor. Military holdouts symbolize both the nation’s past military ethos and the ongoing conversation about its role today, balancing peace with a strong national identity.

Education and the Onoda Story in Historical Narrative

Educational systems use Onoda’s story to illustrate themes of commitment, duty, and misunderstanding. Schools explore his use of the Arisaka Type 99 rifle in the jungles of the Pacific Islands, showing resourcefulness amidst isolation. His saga provides a framework to discuss the broader impacts of war and post-war recovery.

The story of Sergeant Shoichi Yokoi also enriches historical curricula, demonstrating the personal toll of conflict. These narratives encourage critical thinking about obedience, authority, and the complexities of history, helping students engage with past events in meaningful ways.

Frequently Asked Questions

Japanese soldiers’ commitment during World War II resulted in some staying hidden long after the conflict ended. They lived in isolation, often unaware of Japan’s surrender. These soldiers, known as holdouts, have fascinating stories of survival and discovery.

How were some Japanese soldiers discovered years after World War II had concluded?

After World War II, some Japanese soldiers were discovered through chance encounters or searches initiated by friends or family. Local residents often reported sightings, and individuals like Norio Suzuki, who searched jungles, played pivotal roles in locating them.

What is the story of Hiroo Onoda and his extended conflict after World War II?

Hiroo Onoda continued his military duties for nearly three decades in the Philippine jungle, refusing to believe the war had ended. He was discovered by Norio Suzuki in 1974. Onoda only surrendered when his former commander arrived and ordered him to lay down his arms.

In what ways did Teruo Nakamura’s experience differ from other long-holding Japanese soldiers?

Teruo Nakamura, a Taiwanese-Japanese soldier, lived in isolation on Morotai Island in Indonesia. Unlike others, Nakamura had minimal contact with the outside world and built a small hut where he survived until his discovery in 1974, making him one of the last known holdouts.

What are the known facts surrounding Japanese soldiers’ unwillingness to surrender after the war?

Japanese holdouts often feared disgrace and felt immense loyalty to their commands. Instructions to continue fighting, confusion, or lack of knowledge about the war’s conclusion contributed to their extended isolation. They relied on survival skills, maintaining old uniforms and equipment.

What were the circumstances of the final WWII Japanese surrender event?

Shoichi Yokoi surrendered in Guam in 1972, after hiding since 1944. His surrender marked the end of a long period of isolation for him, during which he hid to avoid capture, unaware of Japan’s surrender until locals found him.

In what ways were Japanese holdout soldiers’ experiences documented or shared with the public?

Stories of Japanese holdout soldiers were widely shared through interviews, books, and media. The accounts highlighted their survival skills, personal challenges, and the psychological impact of isolation. These narratives captured public interest, blending history with tales of human endurance.

References and literature

No Surrender: My Thirty-Year War (Hiroo Onoda)

No Surrender!: Seven Japanese WWII Soldiers Who Refused to Surrender After the War (William Web)