The dictates of the Allies in the Versailles Peace Treaty. Reparations, Allied dispute, War guilt issue, Hitler’s rising.

The Treaty of Versailles 1919

Table of Contents

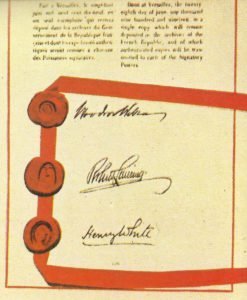

The Treaty of Versailles was a peace treaty signed on June 28, 1919, that officially ended World War I. It was one of the most important and controversial peace treaties of the 20th century.

Overview

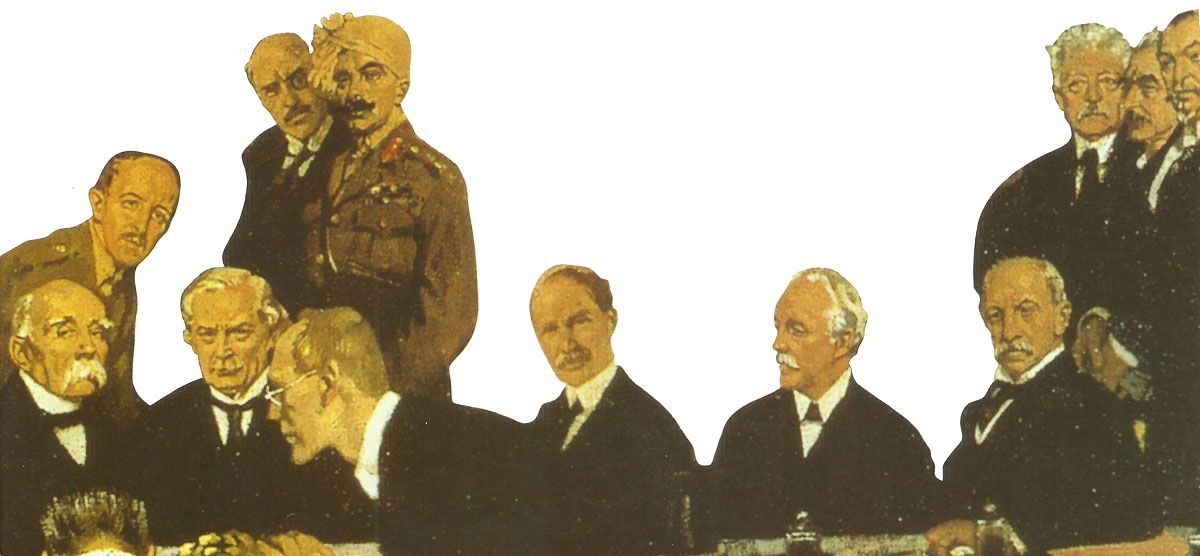

Participants: The treaty was primarily negotiated by the ‘Big Three’ Allied powers – the United States (President Woodrow Wilson), Great Britain (Prime Minister David Lloyd George), and France (Prime Minister Georges Clemenceau).

Main target: Germany, as the defeated Central Power, was the primary focus of the treaty.

Key provisions:

– Germany was forced to accept sole responsibility for causing the war (the ‘war guilt’ clause).

– Germany had to pay substantial war reparations to the Allied powers.

– Germany’s military was severely limited in size and capability.

– Germany lost significant territories, including Alsace-Lorraine, parts of Prussia, and all overseas colonies.

– The Rhineland was to be demilitarized.

– The League of Nations was established as an international organization to maintain world peace.

Consequences:

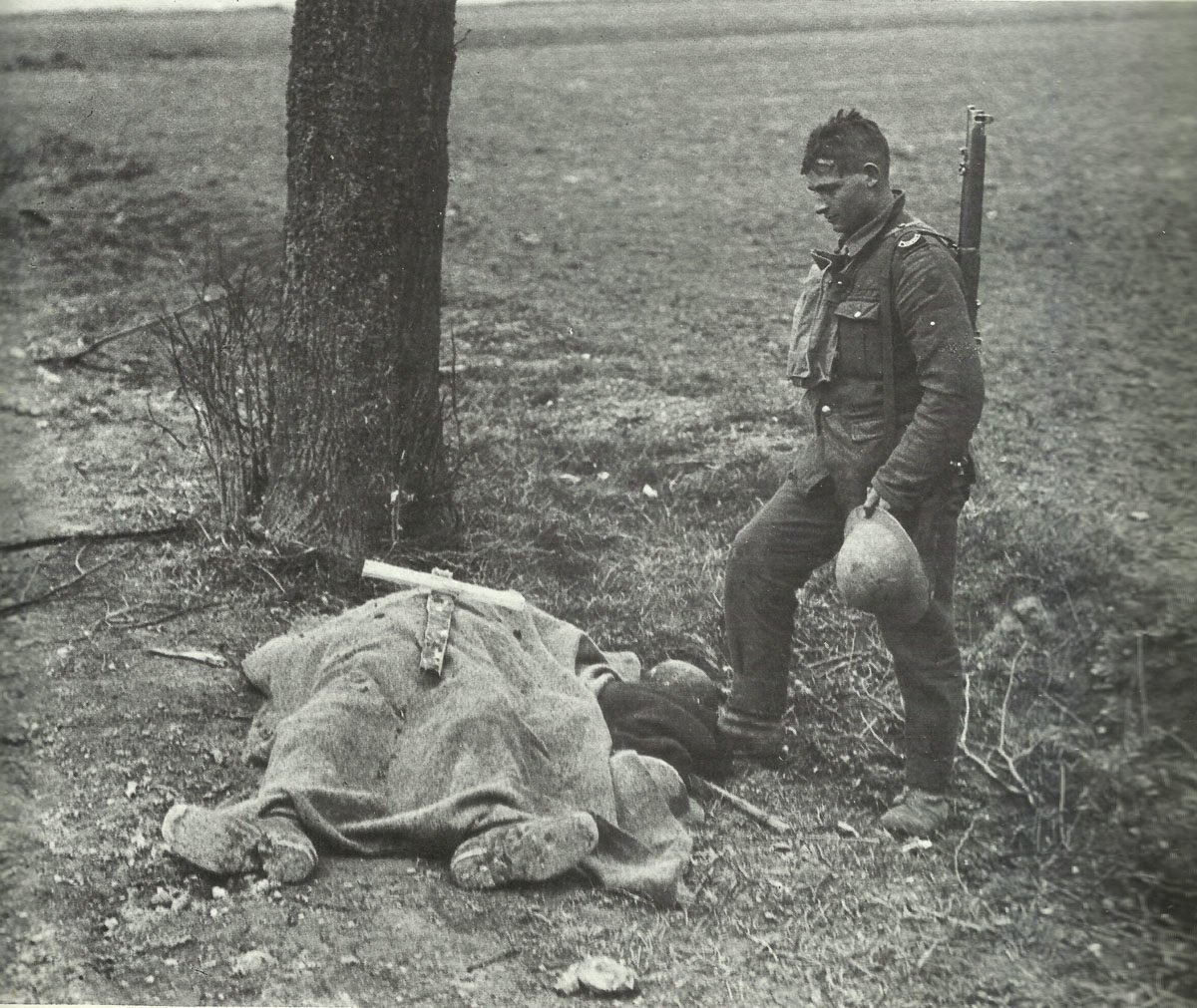

– The harsh terms imposed on Germany led to economic hardship and resentment among the German people.

– The treaty’s provisions contributed to the rise of nationalist sentiments in Germany, which later facilitated the rise of the Nazi Party.

– The United States Senate refused to ratify the treaty, and the U.S. never joined the League of Nations.

Criticism: The treaty was widely criticized for being too harsh on Germany by some (including economist John Maynard Keynes) and not harsh enough by others.

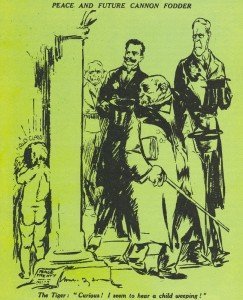

Legacy: The Treaty of Versailles is often cited as a contributing factor to the outbreak of World War II, as its terms fostered resentment and instability in Europe.

The Treaty of Versailles was part of a larger series of treaties (the Paris Peace Conference) that reshaped the political landscape of Europe and the world following World War I.

Reparations

The idea of ‘reparations for damage done’ after a war was not new. The German Reich had also demanded reparations from France in 1871, although practically all fights had taken place on French territory.

At that time France had started the war and had to cede Alsace-Lorraine, which was mostly German-speaking, ‘for all time’ and pay five billion francs in silver in three years, after which the German occupation troops withdrew. His army, fleet, colonies and gold reserves were not touched. And unlike the Treaty of Versailles, the Peace of Frankfurt in 1871 allowed the French population to retain all their property in Alsace-Lorraine, while the Germans were expropriated in 1919.

It is undeniable that the damage in France and Belgium as battlefields of the First World War was enormous and much greater than in Germany, where mostly only damage was caused by the bombs of a few airplanes. Even the German air raids with airships and later bombers on London or the bombardment of British coastal towns by German warships were much more destructive.

In Great Britain, compensation was also claimed for the numerous merchant ships sunk by German submarines. At the same time, however, it was ignored that at least 500,000 German civilians died of malnutrition and deficiencies as a result of the Allied naval blockade and that this blockade continued almost until the forced signing of the Treaty of Versailles – despite the armistice.

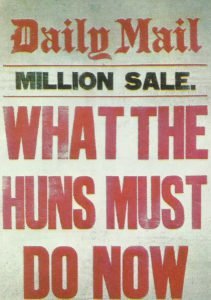

The situation was aggravated by the fact that general elections were finally held in Great Britain again after the interruption caused by the war. And the still heated public cried out for strong reparations.

British Prime Minister Lloyd George was under immense pressure to be re-elected, although since the ceasefire he had tried to enforce a more moderate policy towards the former war opponents.

This also had to do with the fear that too hard conditions on Germany, as well as in Russia and, more recently, Hungary, could lead to a Bolshevik revolution. In fact, Lenin even offered Germany and Hungary a joint alliance with Bolshevik Russia against their common enemies.

However, the reparations claim for a total of around 24 billion British pounds finally demanded in the treaty is impossible for Germany to meet and Reich Justice Minister Otto Landsberg of the SPD and member of the delegation describes it ‘this peace as a slow murder of the German people’.

State Secretary Lansing of the US delegation in Versailles notes in a memorandum that ‘the terms of peace are unspeakably harsh and humiliating, and some are still unfulfillable. It may take years for the oppressed peoples to rebel, but the time will come’.

Even British Prime Minister Lloyd George, in a memorandum, publishes ‘Injustice and arrogance, played out in the hour of triumph, will never be forgiven and forgotten … I can hardly see a stronger cause for a future war …’.

The British economist Kenyes, advisor to the English delegation, writes in 1920 in his book ‘The more often I read the treaty, the worse I get. The biggest crime is the reparations’ clause …’

Even Winston Churchill, Britain’s iron war premier in the foreseeable continuation of the World War, recognizes ‘The economic terms of the Treaty were so vicious and foolish …. Germany was condemned to make senselessly high reparations ….’.

Italy’s Prime Minister Nitti notes ‘Never before has a serious and lasting peace been founded on the plundering, torture and ruin of a defeated people – great people as the Germans are’.

Friedrich Ebert of the SPD says ‘Such forced peace must … become new murder’.

The Dutch envoy Swinderen tells his British colleague that ‘The Versailles peace treaties contain all the seeds of a justify and lasting war’.

At the Labour Party Congress in 1920 Kneeshow speaks ‘If we had been the defeated people and had such conditions been imposed, we … would have begun to prepare our children for vengeance in our schools and homes’.

And the French Marshal Foch correctly prophesies that ‘this is not peace – this is a ceasefire for 20 years’.

The total sum of reparations was reduced in some later conferences and finally fixed at the Lausanne Conference in 1932 at a final payment of three billion Reichsmarks. After the Nazis seized power a few weeks later, Hitler stopped all payments.

It was not until 1953 that the reparations from the First World War were finally regulated in the London Debt Agreement, and the Federal Republic of Germany paid them off, including interest, in installments until 2010.

Great Britain had to pay its debts from the wartime 1914-18 to the USA until the end of the 1960s.

Allied negotiations among each other

In Paris, however, British and Americans found Frenchmen who wanted the maximum reparations and the hardest peace.

To the horror of the Germans, the peace negotiations were no longer conducted on the basis of Wilson’s Fourteen Points, but only on the distribution of the loot on the basis of secret diplomacy during the war.

Germany was only spared the hardest because Lloyd George did not want France to be too powerful and US President Wilson resisted the greed of the winners.

When in April 1919 France’s Marshal Foch demanded an independent Rhine state in which allied troops would be stationed permanently, Wilson became too colorful and returned to the USA. Later, the American Congress will sign neither the Versailles Treaty nor the League of Nations Accession.

Poland and Czechoslovakia also remained smaller than they had hoped due to British and American objections, and the Dutch, who had not taken part in the war, rejected the annexation of the Emsland offered by France. Even the sovereign Luxembourg – occupied during the war – was to fall to either Belgium or France.

The Versailles Peace Treaty was not as vindictive as France demanded, but many of its detailed clauses are punitive in nature and take little account of the rights of individuals.

Article 80, for example, prohibits the merger of Germany and the rest of Austria. In Article 100, the completely German city of Danzig (Gdansk) was turned into an isolated ‘free city’ within Poland’s borders and the entire population lost its German citizenship.

Under Article 118, Germany and all Germans lost their rights, possessions and privileges abroad. Thus, even old prewar economic contracts were lost without replacement and German businessmen lost their assets in Shanghai, Siam, Liberia, Egypt and Morocco.

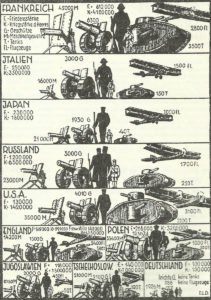

The military clauses limiting the army strength to 100,000 men, the dismantling of fortresses, the dissolution of the air force and the reduction to a small navy could probably be expected. However, the Allies agreed in the Treaty of Versailles to disarm afterwards, which never happened and later legalized Hitler’s rearmament.

One clause, however, was stillborn from the outset when the treaty was signed. According to Article 227, the Allies announced the trial of the German Kaiser for the serious crime against international morality and the ‘sanctity of treaties’. He was to be tried by five judges, an American, an Englishman, a Frenchman, an Italian and a Japanese. Their duty should be to ‘determine the punishment they believe should be imposed’.

Despite the British public’s desire to hang the Kaiser, Lloyd George felt this would be a mistake. When the French finally began demanding the extradition of the Kaiser from Holland, Britain refused to give France any support. The Kaiser remained safely in exile and continued to maintain his garden.

War guilt issue

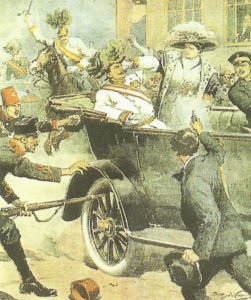

The most controversial clause in the Treaty of Versailles was Article 231, the infamous ‘war guilt’ clause, against which all subsequent German governments protested in vain and which even many British politicians considered too extreme.

The article read ‘The Allied and Associated Governments confirm and Germany assumes responsibility that Germany and its allies are responsible for causing all losses and damage to the Allies and Associated Governments and their nationals as a result of the war caused to them by the aggression of Germany and its Allies’.

The clause is a mockery in view of the murder of the Austro-Hungarian heir to the throne in Sarajevo exactly five years before the signing of the Treaty of Versailles, whose responsibility could be proven even in the highest Serbian government circles – a member of the victorious Allies.

It was not long ago that the world saw, for example, an American government reacting to an act of terrorism by occupying Afghanistan and using flimsy arguments starting a second Gulf War that led to the conquest of oil-rich Iraq. But Austria-Hungary, Germany and its allies obviously had different standards at the time, simply for the simple reason that they let themselves be defeated.

So how did this clause come about? Why were the Allies so concerned that Germany should take responsibility for ‘all losses and damage’? Why was there such blunt talk of ‘Germany’s aggression’?

The war guilt clause came into being before the end of the war. The Supreme War Council, which met in Versailles on 4 November 1918 under the leadership of Clemenceau and Lloyd George, had sent a note to President Wilson explaining to him the need for reparations from Germany. The note began: ‘They (the Allied governments) understand that Germany will be held responsible for the damage caused to the civilian population of the Allies by the invasion of Germany on Allied territory …’.

Since Germany had never denied that Belgium, Luxembourg or France had been attacked, the clause seemed fair, i.e. a generally accepted statement. But someone in the meeting pointed out, when the clause was created, that Germany would then only be liable for the damage caused from the English Channel to the Vosges and there was no economic compensation for the non-continental allies, such as the US, India, Australia, Canada or even Britain. Yet the colonies and dominions in particular had provided many soldiers, workers and materials.

The clause that all Allies receive compensation would therefore have to be reformulated. The new draft, in which the ‘invasion of Allied territory by Germany’ was replaced by ‘the aggression of Germany’, could now be interpreted much further and would thus cover every aspect of war costs.

The justification for the invasion was an Allied self-defense; the ‘aggression’ was a word that was morally reprehensible and thus clarified for all the guilt and thus the right to reparations.

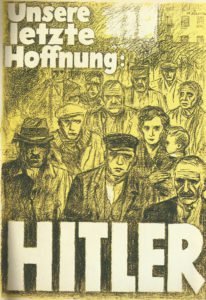

This clause shattered post-war relations between the former allied states and Germany and caused enormous bitterness among the German population, even becoming Hitler’s best election campaigner.

Final consideration

Extremists and populists, just as Hitler was one, can only come to power on the breeding ground of economic hardships and crises.

Thus the Treaty of Versailles was imposed on the German representatives, since the threat was made by an Allied invasion of unoccupied Germany and continuation of the hunger blockade. It was therefore not an ‘agreement’, as the Treaty likes to be quoted.

For many people in Germany and Austria, the retaliation against Serbia was perfectly legal, as was the attack across Belgium on France, which was lusting for revenge for 1870-71 – with Russia already mobilizing behind Germany in the east – pure self-defense against the stronger alliance.

The armistice was offered by Germany to the Allies on the basis of Wilson’s Fourteen Points in November 1918. However, a weak German transitional government threatened by the revolution could no longer hope for at least temporary continued resistance by force of arms in order to avoid the extortion already apparent at that time.

The excessive reparations had a considerable influence on life in Germany for the next 13 years and were also to blame for an economic crisis which, of course, had always promoted radical parties. Thus, Nazis and Communists in Germany agreed on one thing: to declare the Treaty of Versailles null and void.

The Treaty of Lausanne with its final payment was granted too late by the Allies to prevent Hitler from seizing power just a few months later.

Finally, the Allies also committed themselves to disarming after Germany. After Germany had disarmed in accordance with the treaty, the Allies did not follow. This was an obvious breach of the treaty that Hitler used for legitimate rearmament.

The ignoring of Wilson’s Fourteen Points, the extorted Treaty of Versailles with its unenforceable reparations, the nonsensical war guilt thesis, the denial of Allied disarmament, and the unnecessary atrocity propaganda during the First World War have shown the German people how little international law and treaty adherence was respected by the Allies after the moderate post-Napoleonic epoch and apparently only the fist law of the strongest applied.

Twenty years later Adolf Hitler was able to continue his right of fist with ‘paying back in the same coin’, breaches of contract and further brutalization of customs, and that this was accepted by large parts of the German population without any scruples.

References and literature

Illustrierte Geschichte des Ersten Weltkriegs (Christian Zentner)

History of World War I (AJP Taylos, S.L. Mayer)

Der Erste Weltkrieg – Storia illustrata della Prima Guerra Mondiale (Hans Kaiser)

Der I. Weltkrieg – Eine Chronik (Ian Westwell)

Chronicle of the First World War, 2 Bände (Randal Gray)

Unser Jahrhundert im Bild (Bertelsmann Lesering)

1939 – Der Krieg, der viele Väter hatte (Gerd Schultze-Rhonhof)