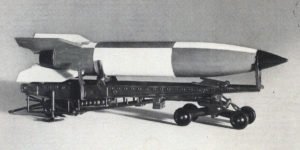

V-2, the German ‘Retaliation Weapon 2’.

Organization, deployment, launch and effect of the ballistic missile A-4 (V-2) in the years 1944 to 1945.

Organization of missile units

Table of Contents

In autumn 1943 it appeared to the Germans that both the ballistic missile A-4 (V-2) of the army and the ‘flying bomb’ Fieseler Fi 103 of the Luftwaffe would be ready for action in spring 1944.

Since both weapon systems had the purpose of firing at Britain, the army formed a joint organization with the ’65th Army Corps for Special Use’ on December 1, 1943. The command over the corps was transferred to the previous commander of the Army Artillery School, Lieutenant General Erich Heinemann. His chief of staff was Colonel Eugen Walter of the Luftwaffe.

The corps moved to its headquarters near St Germain in France in early 1944, but since the V-2 program was still plagued by problems, it concentrated first of all on the deployment of the V-1.

The army’s missile batteries were originally to be commanded by Dornberger, who was exempted from the A-4 ballistic missile development program on September 1, 1943. However, the catastrophic course of the field tests in Poland led to Dornberger’s replacement by an experienced field artillery officer, General Richard Metz. Dornberger, on the other hand, resumed work on the rocket’s technical development program.

Three launcher battalions were formed from the training, replacement and testing units of the A-4 program: Artillery Abteilung (detachment) 836, Artillery Abteilung 485 and Artillery Abteilung 962.

After visiting the first two battalions in the spring of 1944, General Metz was disillusioned with the ability of their officers and crews, and the third battalion was used to bring the first two into shape. Metz was so frustrated by the condition of the units that he resigned his command and demanded a ‘serious’ front command.

In the meantime, Heinrich Himmler had ordered his Waffen-SS to set up its own missile battalion. The SS Launcher Abteilung 500 therefore began to convert its conventional rocket launchers to the new ballistic missile.

The delay in the A-4 missile, the Allied invasion of Normandy and the loss of the first launching bunkers there and the assassination attempt on Adolf Hitler resulted in SS General Hans Kammler taking over the command of operations for the V-2 missile from August 1944, which was withdrawn from the 65th Corps.

At the beginning of the V-2’s first deployment in autumn 1944, each firing battalion consisted of 5 detachments. These included the headquarters’ detachment, the launcher detachment, the radio detachment, the technical detachment and a fuel detachment.

Each firing battery consisted of 39 men organized into five teams. The fire control, the investigation and equipment crew, the engine crew, as well as one team each for the electrics and for the vehicles and trailers.

The radio detachment was responsible for the communications of the unit and selected the fire positions for the batteries.

The technical detachment reloaded the missiles at the railway terminus and transported them on the transport wagon to the intended firing positions. This department had three Vidal trailers for every Meiller trailer to transport the A-4 missiles, resulting in 27 per battalion.

The fuel detachment was divided into three teams, each responsible for one of the fuels: liquid oxygen (LOX), alcohol and sodium permanganate (Z-substance). The battalion had 22 LOX trailers, 48 alcohol tankers, 4 Z-substance trailers and 4 pump trailers.

Launching the V-2

When the V-2s arrived by rail in the area of the planned launch, the technical crew reloaded them onto the Vidal trailers using their De Friese and Strabo 16-ton cranes. The warheads were transported separately from the missiles on their own trains and were only mounted on the missiles at the launch site.

The technical detachment checked the missiles. The rockets were then reloaded onto the Meiller trailer by crane and taken to the launch site. The liquid oxygen was transferred from a special transporter to smaller, insulated trailers.

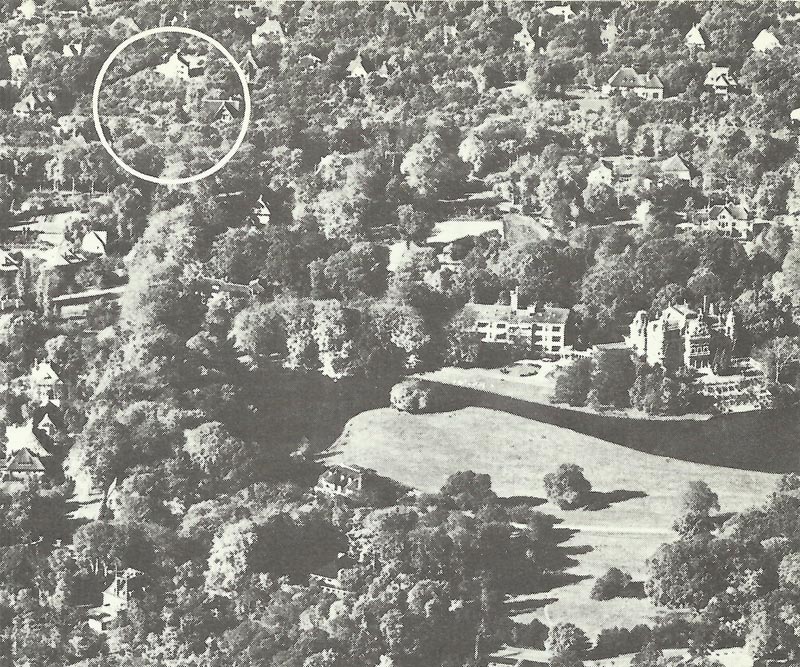

The ideal launch sites were roads with trees on both sides to make it difficult to discover from the air. There, the base plate launcher was mounted behind the Meiller trailers.

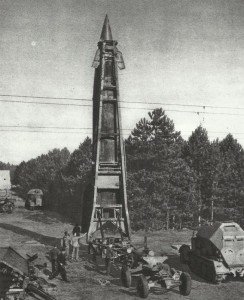

When the rocket was in position, the cable cars and electricity trucks arrived and cabled the rocket and trailer. After the power transmission was established, it took 12 minutes to erect the rocket.

The Meiller trailer remained at the launch site while the rocket was being refueled, as it had a scaffold and ladders for checking the rocket. It then left the site and, after all preparations had been completed, all 32 other vehicles and trailers.

The rocket was checked again and then the fuel tankers and trailers arrived. Two methyl alcohol tankers were needed to fill the rocket’s main tanks in ten minutes. The trailer with the liquid oxygen (LOX) was only brought to the end and its contents were pumped into the rocket so that as little as possible of it evaporated.

The turbo pump of the rocket, which drove the alcohol and LOX into the combustion chamber, needed its own fuel from sodium permanganate and hydrogen peroxide. After the refueling was completed, an electric igniter was placed below the combustion chamber of the rocket engine.

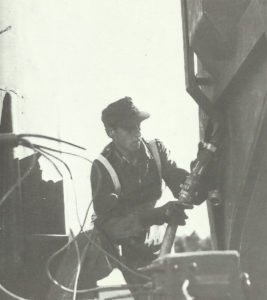

During refueling, a crewman climbed up to the guide bush and connected an electrical cable to transmit commands to the Vertical Inertial Guidance Unit and Flight Control System.

After refueling and preparations were completed, the lifting arm of the Meiller trailer was lowered and the trailer pulled away, while the supply vehicles were brought to a safe distance from the launch site.

After the launch of the missile had been prepared at the right angle, as with conventional artillery, the commander gave the order ‘X minus 10’, which meant that the launch took place in 10 minutes.

Thus, all preparations for the launch took between four and five hours, the last 90 minutes of which were required for erecting, refueling and preparing the missile. About 15 percent of the erected and refueled rockets could not be launched due to malfunction or icing of the liquid oxygen.

The fire control tank, a converted SdKfz-7 half-track vehicle with an armored control room at the rear, was positioned backwards at a distance of 110 to 165 yards (100 to 150 metres) from the launch pad of the missile. If there was enough time, a protective embankment was built in front of the vehicle.

These protective measures were necessary in the event that the rocket broke or exploded on the ramp during ignition.

The fire control tank had four men crew with the commander or his deputy, the technician for the radio, propulsion and the one for the thrust control.

After checking the three control elements in the armored shelter of the vehicle, the start frequency began. First the turbo pump was put into operation, which pressed the LOX and the alcohol into the combustion chamber, where it was ignited by the electric igniter.

At that time the rocket developed about 8 tons of thrust, which was not enough to take off. When it was clear that the engine was working properly, full thrust was given and the rocket took off from its launch pad.

After launch, the A-4 rocket engine worked for 55 seconds. Flight corrections were made by four graphite lamellas in the rocket output for inclination and azimuth and four rudders on the fins for roll and course. The last 25 percent of the built A-4 missiles were additionally equipped with the Lorenz guidance beam system, whereby the autopilot also received a radio receiver. However, the system was not operational until January 1945, and the only unit that regularly used this equipment was the SS Launcher Detachment 500. However, this achieved considerably better hit rates and was even used in the only tactical deployment of the V-2, against the Remagen bridge.

The range of the V-2 was regulated by the burning time of the rocket engine. At the beginning the burning time was controlled by radio and from the end of 1944 by a built-in acceleration sensor.

By the time the combustion engine was extinguished, the rocket had reached a height of about 18.95 miles (30.5 kilometres) and was 17 miles (27.3 kilometres) ahead from the launch site. The maximum speed was reduced from 564 ft/sec (172 m/sec) to 423 ft/sec (129 m/sec) when it reached its apex. At the maximum range of 200 miles (320 kilometres), this was a height of 58 miles (93.3 kilometres) before the V-2 tilted back towards earth. The flight time over the full range was 5 1/2 minutes.

V-2 in action

Compared to modern missiles, the A-4 had only a low probability of hitting. The average deviation from the target was 4.35 to 10.5 miles (7 to 17 kilometres). Only 4 percent of the missiles hit the target within 3.1 to 4.35 miles (5 to 7 kilometres).

Four percent of the missiles did not climb properly after launch, usually within the first 30 seconds.

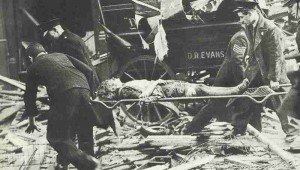

Of the first 1,152 missiles launched against London, 517 hit the city. On impact, the V-2 had a speed of 4,232 ft/sec (1,290 m/sec), more than three times the speed of sound.

The warhead was filled with a 60/40 Amatol mixture, one of the strongest explosives available. Only two of the A-4 missiles did not explode, all others caused a crater 33 ft (10 meters) deep and 40 to 50 ft (12 to 15 meters) in diameter.

Although the action of the V-2 was actually intended against London, the strategic situation in the West forced a change of plans. Now the first blow was to be sent against Paris, which had just been liberated by allied troops. However, the deployment of the Battery 444 was difficult due to the flowing front line situation at this time and so the first deployment of the V-2 could not take place before September 6, 1944. Both missile launches on September 6 failed due to engine failure.

The battery went after combat contact afterwards on 8 September between Sterpigny and Gouvy in Belgium in position and could start the first missile successfully at 8:34 clock. However, the whereabouts of this rocket are unclear, perhaps it exploded in the atmosphere. The second missile was launched at 11 a.m. and hit the southeast of Paris, where 6 people were killed and another 36 injured.

Battery 2 of the artillery detachment 485 went in the meantime at The Hague on 8 September 1944 in position and launched at 18:37 clock two rockets at the same time. The target was the Waterloo station in London and one missile hit the Staveley Road in Chiswick, West London, while the other hit Epping, 17 miles (27 km) north of the city center.

By early March 1945, a total of 1,359 V-2 had been fired against London, 1,039 of them from the Hague area and the rest mainly from Hook van Holland.

Of these, 169 (12 percent) were failures shortly after takeoff, 1,054 reached England and 517 (38 percent) hit London and its suburbs. The losses in England were 2,754 dead and 6,523 wounded.

On Antwerp, even more V-2s were launched. Of the 1,610 missiles launches against this important port city to supply the Allied troops in northwestern Europe, 1,262 (78 percent) struck in this area, but only 598 (37 percent) in the city itself. The target area was the port, but only 152 of the missiles hit it. These attacks were mainly carried out from the Eifel, where the failures were called ‘Eifel fright’ by the local population.

The only tactical operation took place on 11 March 1945 with 11 rockets of the SS-Werfer-Abteilung 500 on the Ludendorff bridge near Remagen. With their new radio control, the missiles hit an average distance of 1.05 to 2.17 miles (1.7 to 3.5 kilometres) from the target. No V-2 hit its target, but for the technical standard at that time this was an exceptional accuracy compared to the other V-2 operations.

V-2 targets:

Country | City | No of missiles |

|---|---|---|

Belgium | Antwerp | 1,610 |

Luttich | 27 |

|

Hasselt | 13 |

|

Tournai | 9 |

|

Mons | 3 |

|

Diest | 2 |

|

France | Lille | 25 |

Paris | 22 |

|

Tourcoing | 19 |

|

Arras | 6 |

|

Cambrai | 4 |

|

Britain | London | 1,358 |

Norwich, Ipswich | 44 |

|

Holland | Maastricht | 19 |

Germany | Remagen | 11 |

TOTAL | 3,172 |

The end of V-2 operations

The crossing of the Rhine by the British forces into northern Germany ended the deployment of the V-2. The last six missiles were fired from The Hague on 27 March against London and the last against Antwerp from Hellendoorn on the same day. Two more missiles were fired on 28 March, but their targets are no longer identifiable.

Subsequently, almost all V-2 ground units were disbanded and converted into infantry combat groups, destroying their equipment.

Only parts of the Artillery Regiment 901 were ordered to bombard Red Army troops on the Eastern Front, who besieged Kuestrin (today Kostrzyn). Due to the chaos in Germany during the last weeks of the war, this ‘Operation Blücher’ could not more carried out.

The original training unit Battery 444 was moved to Schleswig-Holstein, where it undertook some test firings with rockets out into the North Sea.

SS-General Kammler, the infamous head of the underground forced labor complex of Nordhausen, where the ‘miracle weapons’ V-2, V-1 and He 162 Salamander jet fighter were built and who had taken over the operational command of the V-2 missions in autumn 1944, was appointed commander of the Prague defense. There his tracks are lost.

Nordhausen itself was conquered by US troops on April 10, 1945. However, production of the V-2 had already ended in March 1945.

Efficacy

The V-1 was in the final analysis the more efficient weapon than the advanced and much more expensive ballistic missile V-2. Since the warhead of the ‘flying bomb’ did not suffer from heat like the one of the V-2, it exploded less often before the impact at the target and could also use more powerful explosive mixtures. In addition, the impact of the V-2 caused a deep crater, which reduced the blast wave of the explosion to the surrounding area.

And precisely because the V-1 could be intercepted in contrast to the V-2, it forced the Allies to take considerable countermeasures with anti-aircraft rings, balloons, interceptors and the bombardment of their launch positions. So about 25 percent of all allied air raids and 20 percent of the dropped bombs which were carried out from December 1943 until autumn 1944 were against V-1 targets.

In addition, the V-1 was much more effective as a terror weapon because it could be heard long and wide, while the V-2 exploded at the target before it could even be perceived. The constant terror of the London population in the summer of 1944 by the average daily 110 V-1 caused a never officially announced mass exodus from the British capital, while against the subsequent only average daily sixteen V-2 missiles there were no defensive measures anyway.

Users: Germany.

References and literature

V-2 Ballistic Missile 1942-52 (Steven J. Zaloga)

Die deutschen Geheimwaffen – Der Zweite Weltkrieg (Brian Ford)

Luftkrieg (Piekalkiewicz)

According to Speer’s memoirs, the V-2 required a huge amount of skilled talent and scarce raw materials. Perhaps it would have been better to develop a surface-to-air missile against bomber aircraft. A huge, fortified launching facility was built in Northern France to assemble and launch V2s, but it was heavily bombed and then occupied by the Allies.

The key technology of the V2 was its inertial guidance system using gyros. It needed a proximity fuse and larger warhead. von Braun wanted to develop a two-stage design for greater range, but was denied. Slave labor manufacturing introduced many defects.

No doubt, the V1 was a far more efficient weapon!