The Battle of Verdun (February 21 – December 18, 1916).

Situation end of 1915, to bleed the French army white, ‘Sauve qui peut!’, order of sacrifice and the suicide club.

Battle of Verdun 1916

Table of Contents

The Battle of Verdun was one of the longest and bloodiest battles of World War I, fought between the German and French armies from February 21 to December 18, 1916.

Overview

Location: Verdun-sur-Meuse, northeastern France.

Combatants: German Empire vs. French Third Republic.

German Strategy: The Germans, led by Chief of the General Staff Erich von Falkenhayn, aimed to ‘bleed France white’ by attacking a strategically and symbolically important target.

French Response: The French, under the command of Philippe Pétain (later replaced by Robert Nivelle), adopted the slogan ‘They shall not pass’ (Ils ne passeront pas).

Casualties: Estimates vary, but approximately 700,000 soldiers were killed, wounded, or missing (362,000 French and 337,000 German).

Duration: The battle lasted about 10 months, making it one of the longest battles in history.

Outcome: While the Germans made initial gains, the French eventually halted their advance and regained most lost ground by the end of the year.

Significance: The battle became a symbol of French determination and resilience. It also highlighted the brutal nature of attrition warfare in World War I.

Aftermath: The battle severely depleted both armies and had a lasting impact on French military and civilian morale.

Memorialization: The Douaumont Ossuary and other monuments near Verdun commemorate the battle and its casualties.

The Battle of Verdun remains one of the most infamous engagements of World War I, exemplifying the horrors of trench warfare and the massive loss of life characteristic of the conflict.

The situation at the end of 1915

After 1915 deadlock had been come to the length of a static front extending from Switzerland to the Channel. The Germans had been unsuccessful, at the Marne battle, to earn a victory in World War One by a single sledge-hammer strike against their numerically superior opponents, while suffering 750,000 casualties. In trying to repulse the Germans from their ground, France had sacrificed 300,000 death and another 600,000 wounded, captured, and missing soldiers.

Great Britain’s naval might had turned out unsuccessful to take the Dardanelles from Ottoman Empire. Separated Russia staggered on from defeat to defeat, nevertheless the Central powers couldn’t bring the war to an end in the unlimited spaces of the east.

Sir Douglas Haig, who had also just taken over command of the BEF in France from General French, might have favored to strike in Flanders (a choice which was to reassert itself with devastating outcomes one year afterwards). Nevertheless, following a conference with Joffre on 29th December, he made way for himself to be won over to the Somme plan. Nevertheless, on the opposite side of the front, the chief of the German general staff, General Erich von Falkenhayn – an unusual combination of ruthlessness and indecision – got his unique ideas. The Germans would defeat the Allies to the draw.

To bleed the French army white

Potential would certainly not once more look so brilliant for German military as at the end of 1915. In mid-December Falkenhayn wrote an extended memorandum for Kaiser Wilhelm II by which he suggested that the sole method to realize triumph was to destroy the Allies’ major army, the French, by luring it into the defense of an indefensible location. Verdun, located hazardous at the end of an extended salient, around One hundred thirty air miles south-east of where Joffre planned to strike on the Somme and merely One hundred fifty miles due east of Paris, completed all of Falkenhayn’s specifications.

Verdun’s background as a fortified camp went back to Roman days, when Attila had thought it was really worth destroying. During the Seventeenth century Louis XIV’s superb martial expert, Vauban, had created Verdun the strongest citadel in the cordon protecting France; in the Franco-Prussian War of 1870 it turned out the last of the strong French citadels to surrender, outlasting Sedan, Metz, and Strasbourg. Following 1870 it was subsequently the crucial citadel in the line of fortresses protecting France’s frontier with Germany. In 1914, Verdun had granted a strong rock for the French line, and without it Joffre possibly not have managed to fight on the Marne and rescue Paris.

Coming from his expertise each of the historical background and nature, Falkenhayn estimated that France could be pressured to fight for this semi-sacred citadel to the last soldier. By threatening Verdun with a moderate investment of just 9 divisions, he was expecting to lure the main forces of the French army into the salient, where German heavy artillery would likely smash it to pieces coming from 3 edges.

In Falkenhayn’s personal phrases, France was thus to be ‘bleed white’. It had been a strategy completely new to the history of warfare and one that, in its very symbolism, was symptomatic of that Great War where, in their callousness, leaders might consider human lives as simple corpuscles.

The V Army, leaded by the Kaiser’s heir, the Crown Prince, was employed to carry out the triumphant battle. All the time the superb artillery as well as their large munition trains now started to move in the direction of the V Army coming from all other German fronts. Making use of the railways behind their front as well as the national genius for organization, preparations moved with amazing tempo and secrecy. By the start of February 1916 even more than 1,200 guns were in place – for an attack frontage of barely 8 miles (ca. 13 km). Over 500 were ‘heavies’, which includes 13 of the 420 mm Big Bertha mortars, the ‘secret weapon’ of 1914 which had destroyed the theoretically impregnable Belgian forts. No time before had such a concentration of artillery been seen.

Verdun was closer than 10 miles (ca. 16 km) up the tortuous Meuse from the German lines. The majority of its 15,000 inhabitants had departed when the war arrived at its gates in 1914, and its roads had been at this moment filled with military, however, this had been not new for a town which had always been a garrison city.

In significant contrast to the featureless wide open area of Flanders and the Somme, Verdun was between interlocking patterns of large hills and ridges which offered significantly powerful natural lines of defense. The main hills were studded with 3 concentric rings of powerful subterranean fortifications, adding up to almost 20 major and 40 intermediary works.

These fortifications lay among 5 and 10 miles (ca. 8-16 km) from Verdun itself. Between them and no man’s land stretched a defensive system of trenches, redoubts, and barbed wire such as was to be seen all over the entire span of the Western Front. Verdun earned its status as the world’s strongest fortress. Theoretically.

The truth is – regardless of, or maybe as a result of, its fame – by February 1916, Verdun’s defenses had been in a lamentable condition. The fate of the Belgian forts had persuaded Joffre to remove the infantry garrisons from the Verdun citadels, and take away most of their artillery. The soldiers themselves had become slack, lulled by so many weeks stayed in so silent and ‘safe’ a sector, whose misleading relaxed was deepened by the effect of one of the nastiest, rainiest, foggiest, and most enervating environments in France. The French soldier has never been well-known for his enthusiasm for digging in, and the first lines of trenches at Verdun contrasted improperly with the incredibly strong earthworks the Germans had built at their vital areas on the Western Front. And, as opposed to the 22 battalions of elite storm troopers, the Crown Prince deployed prepared for the strike, the French trenches had been manned by only 34 battalions, several of which had been second-class units.

One particular remarkable French officer, Lieutenant Colonel Emile Driant, who leaded 2 battalions of chasseurs within the extremely end of the salient, in fact informed the French high command of the upcoming assault as well as the poor condition of the Verdun defences. For this impertinence, his knuckles had been seriously rapped; the imperturbable Joffre spent limited interest.

‘Sauve qui peut!’

Following a 9 day postpone a result of terrible weather conditions (the initial significant drawback to German schemes), the bombardment started at sunrise on 21st February. For 9 terrible hours it carried on. Even on the shell-saturated Western Front absolutely nothing similar to this had previously been encountered. The improperly organized French ditches had been obliterated, quite a lot of their defenders buried alive. One of the units in contact with the impact of the shelling were Driant’s chasseurs.

Verdun Forces February 21, 1916:

| troops | guns | |

|---|---|---|

| German Fifth Army (Crown Prince, Knobelsdorf) | 140,000 men from 10-19 divisions | 1,220 guns (654 heavy) |

| French Verdun Fortress area (Herr) | 150,000 men in 6 divisions in 60 forts | 270 guns |

At 4 hours that afternoon the bombardment lifted and the first German assault troopers moved on from their admitted locations. This was, indeed, however a powerful patrol action, examining just like a dentist’s probe for the most fragile parts of the French front. In the majority of locations it held. The following morning, the ferocious bombardment started once again. It looked hopeless that any individual could have survived in that methodically worked-over earth. However, a few had, and, with a brave tenacity that was to immortalize the French defense throughout the long months ahead, they carried on to deal with the invisible enemy from what still existed of their trenches.

Driant had been shot in the head while withdrawing the remnants of his chasseurs. Of the 2 battalions, 1,200 strong, a few officers and around 500 men, most of them wounded, were all that finally straggled returning to the rear. However, the French opposition once more prompted the German storm troops to be pulled back, in order to wait for another softening-up bombardment the next morning.

On 23rd February, there have been symptoms of increasing confusion as well as alert in the different HQ’s before Verdun. Phone lines were destroyed by the shelling; messengers were not making it through; entire units were disappearing from the eyes of their own commanders. Order and counter-order had been accompanied by the unavoidable effect. One after the other the French batteries were falling quiet, while some shelled their own positions, in the thought that these had been recently left to the Germans.

24th February had been the time the dam broke. A new division, flung in piecemeal, shattered under the bombardment, as well as the entire 2nd line of the French defenses fell in just a couple of hours.

During that catastrophic day, German benefits equalled the ones from the initial 3 days put together. By the night it appeared almost like the war had once more turn out to be one of movement – the very first time since the Marne battle.

Between the Germans and Verdun, nevertheless, there continue to exist the lines of the citadels – most importantly, Douaumont, the most effective of them all, an excellent bulwark of luxury at the rear of the backs of the retreating poilus. After that, on 25th February, the Germans achieved – practically in a match of absentmindedness – one of the finest coups of the whole war. Acting on their unique motivation, a number of little groups of the 24th Brandenburg regiment, led by a 24-year-old lieutenant, Eugen Radtke (employing infiltration techniques and equipped with trench-clubs and pistols), managed their way straight into Douaumont without losing a single soldier. To their amazement, they discovered earth’s strongest citadel to be almost undefended.

In Germany church bells rang through out the country in order to praise the capture of Douaumont. In France its loss had been appropriately considered to be a nationwide tragedy of the very first degree (afterwards believed to have cost France something like 100,000 men). In the roads of Verdun itself survivors of shattered units ran screaming, ‘Sauve qui peut!’

From his headquarters in Chantilly even Joffre had finally end up astounded by the desperation of occasions. To take over the imminently vulnerable sector, he sent Henri Philippe Petain, France’s outstanding professional in the art of the defensive. Not any general owned the trust of the poilu more than Petain. At this moment – in tragic paradox – this distinctively humanitarian general had been required to issue his soldiers to what was turning out to be the most inhuman battle of the entire war. Petain’s orders were to defend Verdun, ‘whatever the cost’.

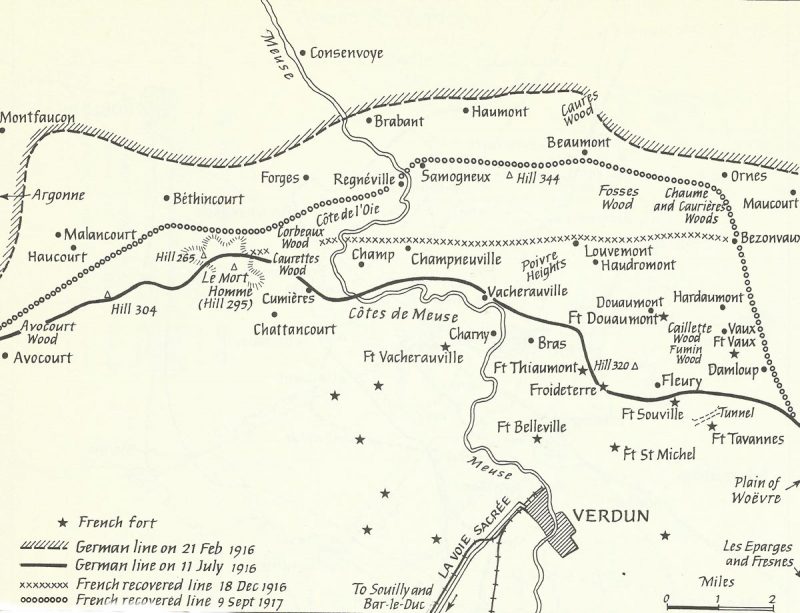

However, the German strike had been starting to slow down. Casualties had been recently much larger than Falkenhayn had anticipated, a lot of them caused by flanking fire coming from French artillery across the Meuse. The German front looped across the river towards the north of Verdun, and, from the beginning, the Crown Prince had pressed that his V Army be permitted to strike alongside each bank at the same time. But Falkenhayn going on to maintain his own outlay of infantry in the ‘bleeding white’ tactic down to the barest lowest – had declined, limiting operations to the right bank. At this point, to clear the risk of the French artillery, Falkenhayn unwillingly decided to expand the offensive across to the left bank, issuing for this reason an additional army corps from his much hoarded reserves. The fatal escalation of Verdun had been arrived.

Order of sacrifice

The lull prior to the following stage of the German offensive allowed Petain to strengthen the front to a virtually sensational degree. He arranged a road artery to Verdun, afterwards named the Voie Sacree, along which the entire lifeblood of France was to strain, to bolster the vulnerable city; during the crucial first 7 days of March alone 190,000 soldiers marched up it.

The Crown Prince at this point started a fresh all-out strike down the left bank in the direction of a small ridge known as the Mort-Homme, which, using its scary name, obtained from some long-forgotten tragedy associated with another time, was to be the heart of the most awful, see-saw battling for the greater part of the following 90 days. In this particular single small sector a monotonous, fatal routine had been setting up that carried on virtually without let-up. This typified the entire battle of Verdun. After hours of saturating bombardment, the German assault troopers would move forward to take what still existed of the French front line. There were not anymore any kind of trenches; what the Germans captured had been in most cases clusters of shell holes, in which individual groups of soldiers survived and rested and died guarding their ‘position’ with grenade as well as pick helve.

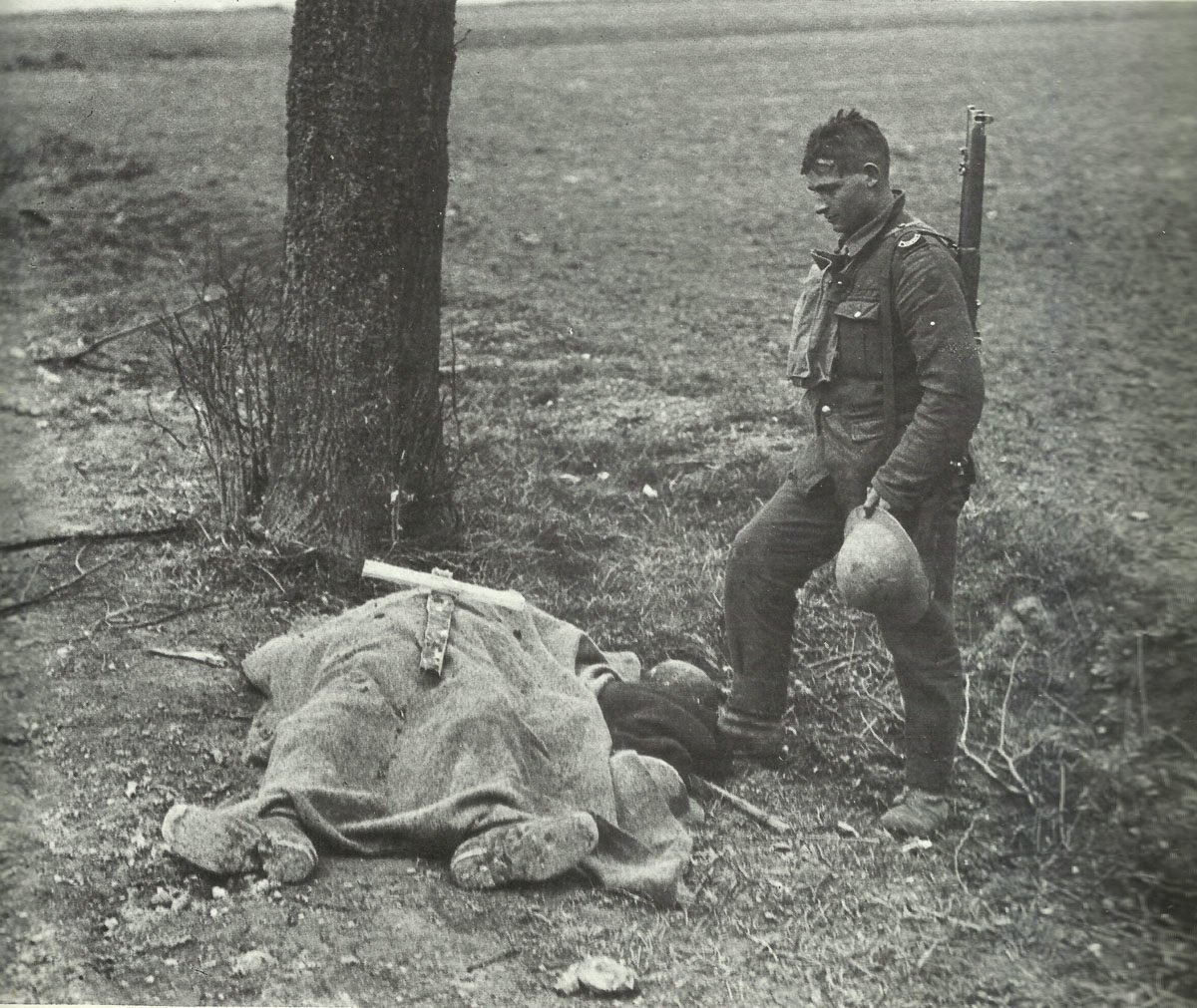

At Verdun the majority died without previously having seen the enemy, under the murderous non-stop artillery bombardment, which began to characterize this battle probably more than every other. ‘Verdun is terrible’, wrote French Sergeant-Major Cesar Melera, who had been killed a couple of weeks prior to the armistice, ‘because soldier is battling with material, with the experience of striking out at vacant air …’.

Explaining the consequences of a bombardment, Paul Dubrulle, a 34-year-old Jesuit in the role of an infantry sergeant (as well later on killed), stated: ‘The best strong nerves can’t withstand for long; the second will come in which the blood mounts towards the head; where fever injuries your body and where the nerves, fatigued, turn out to be not capable of responding … ultimately one abandons oneself to it, you have no more even the power to cover yourself with your package as defense against splinters, and you rarely continue to have remaining the power to hope to God.’

Regardless of the brave sacrifices of Petain’s soldiers, every day brought the ocean of Germans several yards closer to Verdun. By the end of March, French casualties totaled 89,000; however the attackers had also sacrificed virtually 82,000 men. Even after they had captured the Mort-Homme, the Germans found themselves hamstrung by French artillery on the Cote 304, one more ridge still farther out on the flank. Just like a doctor treating galloping cancer, Falkenhayn’s blade had been lured ever further away from the initial point of the plan. Additional fresh German divisions were thrown into the battle – on this occasion to get Cote 304.

Certainly not before May was the German ‘clearing’ ‘operation on the left bank of the Meuse finally carried out. The ultimate drive in the direction of Verdun could start. However, the Crown Prince was at this point for calling off the offensive, and even Falkenhayn’s passion was waning. The strategic importance of Verdun had long since given out of the picture; however the battle had in some way reached a demonic presence of its own, beyond the control of generals of either army. Honor became associated to a degree which made disengagement hopeless. On the French side, Petain – influenced (too seriously, as outlined by Joffre) by the horrors he had seen – had been promoted and exchanged by a couple of far more ferocious persons: General Robert Nivelle and General Charles Mangin, nicknamed ‘The Butcher’.

At this point soldiers had become almost conditioned to dying at Verdun. ‘One eats, one drinks next to the victims, one rests in the middle of the death, one jokes and sings together with corpses’, published Georges Duhamel, the poet and dramatist, who had been becoming a French military doctor. The extremely compacted section of the battlefield itself had become a reeking wide open graveyard where ‘you discovered the victims embedded in the walls of the trenches; heads, legs and half-bodies, just as they had been shoveled out of the way by the picks and spades of the working party’. Conditions weren’t any longer superior for the attacking Germans; as one soldier wrote home in April under the French counter-bombardment: ‘Many would prefer to withstand starvation compared to make hazardous expeditions for meal.’

On 26th May ‘very excited’ Joffre traveled to Haig at his Headquarters and appealed to him to relocate the day of the Somme offensive. When Haig mention of 15th August, Joffre yelled that ‘The French Army might disappear if we didn’t do anything right at that moment.’ Haig eventually decided to assist by attacking on 1st July instead. Despite the fact that Haig occupied strange dreams of a breakthrough to become exploited by cavalry, neither he nor Rawlinson – whose British 4th Army would attack in the battle – had nevertheless reached any better strategic objective than that of relieving Verdun and ‘to wipe out as many Germans as possible’ (Rawlinson).

Verdun Forces June 1, 1916:

| troops | guns | |

|---|---|---|

| German Fifth Army (Crown Prince, Knobelsdorf) | 20 divisions | 2,200 guns (1,730 heavy) |

| French Second Army (Nivelle) | 20 divisions | 1,200 guns (570 heavy) |

At the same time, at Verdun the start of a torrid June introduced the most hazardous stage in the 3 1/2 month battle, with the Germans throwing in a weight of assault similar to that of February – however this occasion focused along a front just 3 miles (ca. 5 km), rather than 8 miles (ca. 13 km) large. The battling arrived at Vaux, the second of the superb citadels, where 600 soldiers commanded by Major Sylvain Eugene Raynal in a legendary defense delayed the primary push of the German V Army for an entire 7 days before thirst caused them to surrender.

Suicide Club

Then, just as Vaux had been lost, the first of the Allied summer offensives was unleashed. In the east, General Brusilov hit at the Austro-Hungarian with 40 divisions, having an extraordinary first triumph. Falkenhayn was pushed to shift units desperately required at Verdun to boost up his defeated ally. Verdun was reprieved; despite the fact that it wasn’t before 23rd June that the real dilemma was come to. That day, working with a lethal new gas known as phosgene, the Crown Prince (unwillingly) assaulted in the direction of Fort Souville, astride the final ridge in front of Verdun. At a particular time, machine-gun bullets were hitting the city roads. Even now the French held however there were threatening symptoms that morale was breaking. Simply how much might an army stand ?

48 hours afterwards, nevertheless, the rumble of heavy British artillery had been noticed in Verdun. Haig’s 5-day initial bombardment on the Somme had started. Over the following days Verdun had been ultimately and for sure relieved by the severe British sacrifices on the Somme.

On 11th July, one further serious effort was set up towards Verdun, and a couple of Germans briefly arrived at a height whence they could in fact look down on Verdun’s citadel. It absolutely was the high-water mark of the battle and also the turning point. Promptly the wave now receded at Verdun, with Falkenhayn ordering the German army to assume the defensive all over the Western Front.

By the end of August Falkenhayn was replaced by he impressive mixture of Hindenburg and Ludendorff.

In the fall months, Nivelle and Mangin recaptured forts Douaumont and Vaux in a number of excellent counter-strokes – in addition a lot of the land captured so hurtful by the Crown Prince’s soldiers. By Christmas 1916 the battle of Verdun and at the Somme were over. Following 10 horrible months Verdun had been rescued. However, at such a price !

Fifty percent the homes inside the city alone had been wrecked by the long-range German artillery, as well as 9 of its neighboring towns had disappeared off the face of the world.

Once the human casualties came to be added up, the French publicly stated to having sacrificed 377,231 soldiers, of whom 162,308 had been outlined as killed or missing. German casualties came to at least 337,000. However, the truth is, joined together casualties may simply have totaled even more than 800,000.

What created this imprecision about the slaughter at Verdun, along with rendering the battle it is really dreadful dynamics, had been the truth that everything happened in so limited space – minimal bigger than the London parks. A lot of the victims were never discovered, or continue to be found even today. One soldier remembered how ‘the shells disinterred the bodies, the reinterred them, cut them to parts, played with them as a cat performs having a mouse’.

Within the great somber Ossuaire at Verdun rest the bones of over 100,000 unidentified soldiers.

Verdun Losses February 21 – December 18, 1916:

| casualties | equipment | |

|---|---|---|

| French | 362,000 (66 divisions engaged) | ? |

| German | 336,861; incl 17,387 PoWs (42 divisions engaged) | c. 46+ guns; 44+ mortars; 107 MGs; c.80+ aircraft; 6+ balloons |

Verdun hat ‘bled white’ his own army, Falkenhayn’s harsh experiment had been unsuccessful. However, in its longer-range outcomes, it held a component of good results.

As Raymond Jubert, a young French ensign, published in prophetic melancholy just before he was wiped out at Verdun: ‘They won’t be able to make us try it again a later date; that would be to misconstrue the value of our effort …’

The too many sacrifices of the French military at Verdun germinated the signs of the mutinies that were to grow during summer of 1917, thereby making it eventually clear that World War One could no longer be won alone.

References and literature

Illustrierte Geschichte des Ersten Weltkriegs (Christian Zentner)

History of World War I (AJP Taylos, S.L. Mayer)

Der Erste Weltkrieg – Storia illustrata della Prima Guerra Mondiale (Hans Kaiser)

Unser Jahrhundert im Bild (Bertelsmann Lesering)