Myths about the Waffen-SS (Part II).

Crimes of the Waffen-SS: Einsatzgruppen (special task forces), concentration camp guards and war crimes.

Myths of the Waffen-SS

Table of Contents

War crimes committed by the Waffen-SS

The Waffen-SS was the military branch of the SS (Schutzstaffel), an organization that was a central part of the Nazi regime’s apparatus of terror and repression. The Waffen-SS was involved in numerous military operations during World War II, and its members committed a range of war crimes and atrocities.

Overview about some of the most notorious examples

Massacres of Prisoners of War (POWs): Members of the Waffen-SS were responsible for the murder of POWs, who were supposed to be protected under the Geneva Conventions. One infamous example is the Malmedy massacre during the Battle of the Bulge in December 1944, where members of an SS Panzer division killed 84 American prisoners of war.

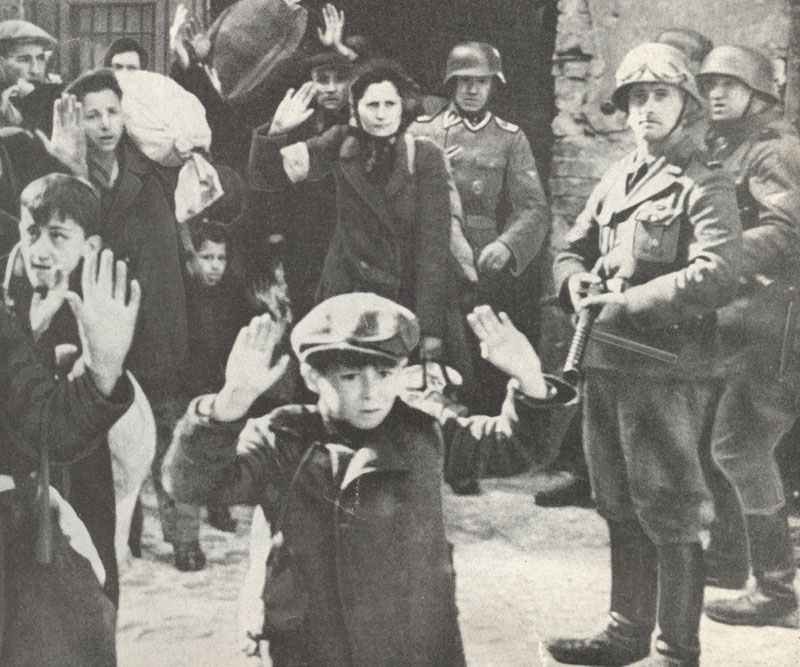

Participation in the Holocaust: The Waffen-SS played a significant role in the Holocaust, the genocide of six million Jews, as well as millions of other victims including Poles, Soviet civilians, Romani people, disabled individuals, and others. Some Waffen-SS units provided direct support to the Einsatzgruppen, the mobile killing squads responsible for mass shootings, and others guarded concentration and extermination camps.

Massacres of Civilians: The Waffen-SS was involved in numerous massacres of civilians in occupied territories. For example, the SS Division Reich was responsible for the destruction of the French village of Oradour-sur-Glane, where 642 men, women, and children were killed in June 1944.

Anti-Partisan Warfare: In the course of fighting Partisans, especially on the Eastern Front, Waffen-SS units carried out brutal reprisals against civilians, often burning villages and executing residents as collective punishment for resistance activities.

Forced Labor: The Waffen-SS used forced labor extensively, subjecting prisoners of war and concentration camp inmates to inhumane working conditions in support of the war effort. This included working in armaments factories, construction projects, and in support roles for the SS.

Medical Experiments: Some SS doctors conducted unethical and brutal medical experiments on prisoners, including those in concentration camps. While this was not the primary function of the Waffen-SS, the organization was complicit in these crimes by providing prisoners and security.

Deportation and Extermination of Populations: The Waffen-SS was involved in the deportation of Jewish people and other targeted groups to ghettos and extermination camps, where they faced systematic murder.

After the war, the Nuremberg Trials and subsequent war crimes trials held many leaders of the Nazi regime accountable for their actions, including those in the Waffen-SS.

The SS, including its Waffen-SS branch, was declared a criminal organization due to its involvement in war crimes and crimes against humanity. Many members of the Waffen-SS were tried and convicted for their roles in these atrocities. However, the scale of the crimes and the number of perpetrators meant that many individuals never faced justice. The legacy of the Waffen-SS’s involvement in these crimes continues to be a subject of historical research, remembrance, and education.

Special task forces and concentration camp guards

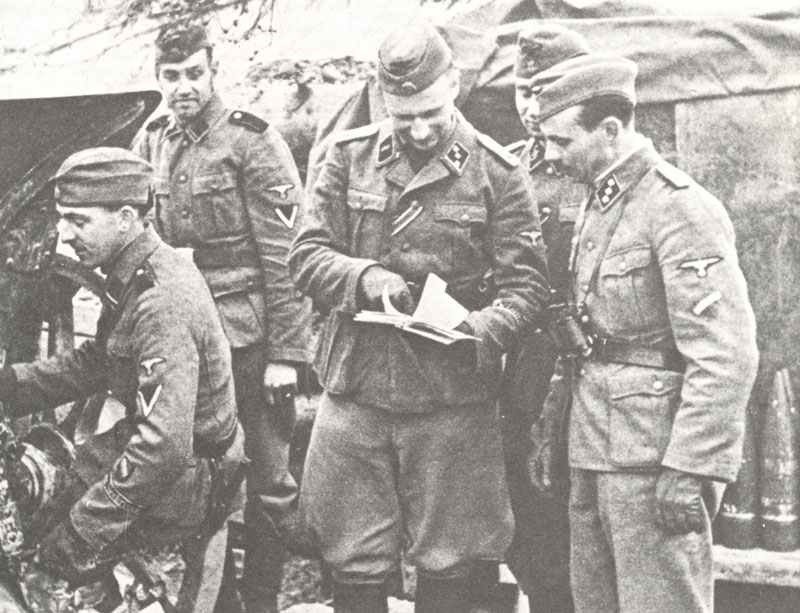

Contrary to the original concept of Hausser and Steiner, Reichsführer-SS Himmler had added numerous other units to the Waffen-SS, which had little to do with the actual combat mission of the troops. These included the mass murder of the Einsatzgruppen (special task forces) and also the concentration camp guard units, the so-called Totenkopf guard battalions. Their soldiers also wore Waffen-SS paybooks and the Einsatzgruppen also had members from Waffen-SS soldiers, as well as members of the Army Military Police, SD men (SS Security Service) and volunteer foreigners. These hangmen and guards were not trained for or intended for combat.

Veterans of the Waffen-SS have therefore repeatedly pointed out that they had no say in these highest political decisions as to which men were accepted into the Waffen-SS, and in many cases they were not even aware that they were organizationally linked to such groups.

In the minds of the survivors of the SS combat troops, they and their Germanic comrades were the ‘real’ Waffen-SS and the other elements were merely a circumstance of war. In their written memoirs the veterans emphasize those details which were important to them. That was above all that they regarded themselves as an elite troop, which had fought bravely in many battles and mostly served honorably. They claimed that they had been ‘just as much soldiers as the others’ from the German army and at least the SS men themselves saw this claim as justified.

What makes this claim difficult is the fact that the Waffen-SS consisted of so many other elements as described at the beginning. The situation is made even more confusing by the fact that there was a varying degree of personnel exchange between the Einsatzgruppen, the Totenkopf guard battalions and the combat troops.

Many people often focus on the negative, highlighting the various questionable associations associated with the Waffen-SS that began dishonorable actions during the war.

However, this was not the Waffen-SS, which Hausser and Steiner originally wanted to found in the 1930s. The disputes with the political leadership over their vision resulted in a prejudgment of all fighting members of the Waffen-SS, such as those of the SS Division Reich and 1st SS Panzer Division Leibstandarte-SS-Adolf Hitler, as well as all German conscripts drafted against their free will in the last year of the war and the voluntary, highly motivated foreigners or ethnic Germans.

War Crimes

If the problems of the service of ethnic Germans in the Waffen-SS are already complex and easily misunderstood, this also applies to the war crimes and atrocities committed by these units.

There is much speculation and suspicion on both subjects, often in the absence of solid facts. The war and post-war propaganda also watered down this topic and thus played into the hands of many people who wanted to see the Waffen-SS as responsible for almost all war crimes and thus acquitted the members of the Wehrmacht of this.

There is a widespread belief that the Waffen-SS men were politically indoctrinated soldiers in one way or another. The exact interpretation varied depending on the perspective of the respective observer.

For this reason, it was assumed that the majority of German war crimes in World War II were committed by the Waffen-SS.

Contemporary witnesses and their written records, however, support the assertions of many veterans of the Waffen-SS that political indoctrination was at most a small part of the training. For political, ethnic and historical indoctrination in the Third Reich already took place in the National Socialist youth groups, such as the ‘Deutsche Jugend’ (German Youth) or ‘Hitlerjugend’ (Hitler Youth).

Membership of the Hitler Youth or its various subdivisions became compulsory as early as 1936 and National Socialist indoctrination was underpinned by the state and by the design of the curriculum in schools and universities.

With the help of this system it was possible to influence a generation of young people up to and including those born in 1928, who were called up for military service during the Second World War.

The youth influenced in this way served primarily in the Wehrmacht (German armed forces), which increasingly affected the German army (Heer) in particular during the war. Throughout the entire Third Reich, the German army consisted mainly of German men, with ethnic Germans and foreigners making up only a small proportion.

In contrast, the Waffen-SS always consisted of between 33 and 50 percent ethnic Germans or foreigners. These young men had not grown up in the atmosphere of National Socialist indoctrination and had not come into contact with the racial or other toxic ideas of National Socialism.

Although some of them had been influenced by fascist or other chauvinist tendencies, few of them had been exposed to indoctrination, let alone the propaganda education provided by the Nazi organizations in Germany at that time.

Thus, the Waffen-SS as an organization had a smaller proportion of young men than the Wehrmacht or, in particular, the army, who had grown up under the teachings of National Socialism.

In the opposite direction, however, the fact that the majority of German citizens who served with the Waffen-SS had volunteered for it had an effect. It can therefore be assumed that these volunteers tended to have a greater conviction of the National Socialist teachings.

However, there was also a high percentage of young volunteers for the German army, navy or air force.

Thus, it is hardly correct to characterize the Waffen-SS as an association of mostly Nazi fanatics. Probably its members were on average less or by no means more indoctrinated than their relatives in the army.

In order to explain the bad reputation of the Waffen-SS, it is useful to examine the effects of political opportunism and the nature of the warfare against Partisans.

Especially the elite armored divisions of the SS were a closed group and a not to be overlooked target for alleged war crimes already during the war, because they were responsible for many losses and also defeats of the Soviets and Western Allies and one was also obviously out for revenge. Sometimes they were also accused by German military leaders, especially when the operations planned with them did not bring the desired result.

After the end of the war, these units and also others of the Waffen-SS were held responsible for the majority of war crimes, while only a few accusations were made against units of the army, even where they may have been justified.

Interestingly, separate criminal offenses were found for each of the first eight SS divisions, as well as for the sister divisions of three of these units. These incidents have sometimes been little investigated, but are considered to be at face value, and the few facts are repeated in countless works which, with their meager content, warm up one another.

In individual cases, the 1st SS Panzer Division with the Malmedy massacre, the 2nd SS Panzer Division with Tulle-Oradour, the 3rd SS Panzer Division with Le Paradis, the 4th SS Police Panzergrenadier Division with Larissa, the 5th SS Panzer Division Viking with the murder of 600 Galician Jews shortly after the start of Operation Barbarossa, the 6th SS Northern Division with the destruction of Rovaniemi in Finland, the 7th SS Volunteer Mountain Division and the 8th SS Cavalry Division with massacres in their respective operational areas, the 12th SS Panzer Division Hitlerjugend with the murder of Canadian prisoners of war in Normandy, the 13th Waffen Mountain Division also with massacres in their operational areas, and the 16th SS Panzergrenadier Division with the massacre of Marzabotto in Italy.

Unfortunately, it cannot be the task here to examine each individual case in more detail. It is essential, however, to point out that most of the cases were in response to some previous atrocities committed in violation of the laws and customs of war, which were often also of an exceptionally heinous nature.

In other words, they were often part of the fatal cycle of atrocities resulting from previous similar acts committed by the other side.

Each case would have to be examined individually and carefully before a generalizing statement about the character of the Waffen-SS could be made.

Detailed investigation shows many interesting sub-areas of the different storylines. For example, Fritz Knöchlein was made a martyr by nationalist circles after his execution for the murder of British prisoners of war in Le Paradis in 1940, because there is evidence that he simply reacted to previous war crimes committed by the British. But to make a heroic figure out of Knöchlein, however, is going too far, because statements by veterans and entries in his file prove that he was a bad regimental commander and an officer of repulsive character at the end of 1944.

Another case that demonstrates the value of continuous and accurate research is the burning of the town of Rovaniemi in Finland. A late war memoir by a Finnish commando revealed that the town was destroyed not as a result of a deliberate and superfluous ‘burnt-earth’ tactic, but as a result of a German ammunition train parked at the station being blown up by the commando soldiers.

The retaliatory action in and around Marzabotto in Italy in the autumn of 1944 is usually referred to as an ‘SS crime’. However, it was not a purge against partisans, as usually ordered by German police or security services. Rather, it was a military operation led by the Luftwaffe’s First Parachute Corps to eliminate the threat to its rear area and lines of communication.

The extent and sequence of the shootings in and around this mountain village are still contradictory to this day. About 700 to 1,000 civilians died there, depending on the origin of the source. However, this does not reveal how many of the victims died as partisans or civilians as a result of the fighting and who may have been killed by organized reprisals.

The situation is further complicated by the fact that the region of Emilia-Romagna, where Marzabotto is located, was then controlled by the Communists and still is over 50 years later.

Since there is no more poisonous political enmity than that between fascists and communists, the first victim, as in many similar cases, is always the truth.

‘Anti-Partisan war’ is the key term in so many of these cases, as the incidents involving the divisions ‘Das Reich’, ‘Prinz Eugen’, ‘Florian Geyer’ and ‘Reichsführer-SS’ show.

Before any judgement can be passed on this, it must be pointed out that before and during the Second World War, reprisals against the civilian population in occupied territories were permitted as a last resort by customary war law, including the principles of the so-called Martens clause in the preamble to the Convention, i.e. ‘the customs established among civilized peoples’, ‘the laws of humanity’ and ‘the dictates of the public conscience’.

The right to reprisals against civilian hostages at that time was expressly confirmed by the court of the seventh follow-up trial of the International Military Tribunal in Nuremberg in 1948. It was only on 12 August 1949 that the Hague Convention banned it with regard to the protection of civilians in times of war, collective punishment, intimidation or terror measures against the civilian population, as well as reprisals against individuals and hostage-taking (Article 33).

According to the war customs of the land war at that time, not every killing of a civilian by men of the Waffen-SS was a crime, even before the question arises whether the killing of unarmed civilians together with those who took up arms was intentional or the effect of the fight – i.e. collateral damage.

Clear massacres, such as the executions in Lidice and the destruction of the town in response to the murder of Reinhard Heydrich, had never been permitted by international law. In this case, no soldiers of the Waffen-SS were involved either, but men of the Gestapo, SD, and German and also Czech police units. However, reprisals against civilians were permitted to a certain extent.

Since the Allied post-war revision of international conventions, these inglorious aspects of warfare have been removed and the people of our time generally find such acts incomprehensible and reprehensible. The same is true of terror bombing and targeted attacks on civilians, where the Allies in particular have not ‘dressed up’ in glory.

But this was neither the law nor the general opinion during the Second World War. Even the US field manual under 27-10 from the wartime in 1940 allows in the rules of land warfare hostage-taking and reprisals against civilians under special circumstances to ‘lead the enemy to refrain from illegitimate practices’.

So, in order to get to the bottom of these incidents, the nature of guerrilla warfare must be taken into account. Such incidents took place long before the Second World War and have been taking place continuously in areas such as Vietnam, Somalia, Iraq and Afghanistan ever since.

When the Axis Forces operated in the Balkans between 1941 and 1945, they became involved in a style of warfare that had existed there for centuries and was resumed five decades later in the same regions. ‘Ethnic cleansing’ has been practiced in the Balkans at intervals for centuries, long before the arrival of the Germans, and was repeated not long ago in the disintegrating Yugoslavia.

The Waffen-SS, with its connections to the German police and security forces, used a considerable proportion of its units to fight partisans. This happened not only in southeastern Europe, but also in Russia, Italy and elsewhere. These units were caught up in an unusually cruel and merciless cycle of warfare characteristic of partisan activities. These experiences were also shared by some units of the former Allies from the Second World War in the subsequent colonial, bush and anti-terrorist wars. These incidents are mostly very shocking and sometimes inexcusable, but not unique to the Waffen-SS.

So it is the area of operations against partisans where the mass of atrocities committed by the Waffen-SS can be found. If one understands this and the causes, it is important to make a judgement on the basis of the requirements of that time for the rules of land warfare. Under no circumstances, however, according to our modern land warfare rules and views on warfare which do not correspond to the guidelines given to the members of the German armed forces of that time and especially to the elements of the Waffen-SS who were involved in the fight against partisans.

References and literature

The Waffen-SS (Martin Windrow)

Waffen-SS Encyclopedia (Marc J. Rikmenspoel)

Hitler’s Elite – The SS 1939-45 (Chris McNab)