Warsaw Uprising 1944: Poland’s Heroic 63-Day Battle Against Nazi Occupation.

Warsaw Uprising 1944: Poland’s Heroic 63-Day Battle Against Nazi Occupation

Table of Contents

The Warsaw Uprising was a major operation by the Polish resistance during World War II. It began on August 1, 1944, and lasted for 63 days. The goal was to free Warsaw from German control before Soviet forces arrived.

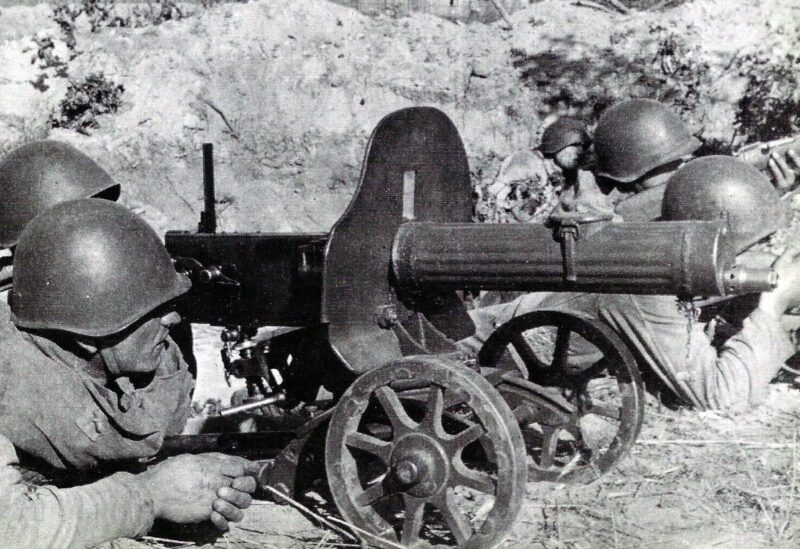

The uprising involved about 50,000 Polish fighters against a much larger German force. They fought bravely, but faced many problems. The resistance lacked weapons and supplies. German troops were strong and well-equipped. The Soviets, who were close to Warsaw, did not help.

The uprising ended on October 2, 1944 with the formal surrender of the ‘Armia Krajowa’, the Polish Home Army. Many people died, and much of Warsaw was destroyed. The Germans kept control of the city until Soviet troops captured it in January 1945. The Warsaw Uprising showed the Polish people’s strong will to be free, even if it failed to reach its main goal.

Prelude to the Uprising

The months leading up to the Warsaw Uprising saw intense planning and coordination between Polish resistance forces and the exiled government. Key operations and decisions set the stage for the eventual outbreak of fighting in August 1944.

Operation Tempest and Forming of the Plan

Operation Tempest was a series of uprisings against German forces as the Soviet Red Army approached Polish territory. The Polish Home Army (AK) carried out attacks to liberate areas before Soviet arrival.

General Tadeusz Komorowski, AK commander, received orders from London to prepare for a national uprising. The AK developed plans to seize control of Warsaw and other major cities.

As Soviet forces neared Warsaw in mid-1944, the AK stepped up preparations. They gathered weapons, organized units, and mapped out key targets in the city.

The Role of the Polish Government in London

The Polish Government-in-Exile in London played a crucial part in planning the uprising. They hoped to assert Polish sovereignty before Soviet occupation.

Prime Minister Stanisław Mikołajczyk pushed for action to strengthen Poland’s position. The government sent instructions and resources to the AK through secret channels.

There were debates about timing. Some wanted to wait for Allied support. Others felt they needed to act quickly before the Soviets took control.

The government approved the final plans for the uprising in July 1944. They believed it was vital to show Polish resolve for independence.

Strategic Overview of the Uprising

The Warsaw Uprising aimed to liberate the city from German control. It involved complex military tactics and took advantage of Warsaw’s unique geography.

Military Strategies and Objectives

The Polish resistance Home Army led the uprising. Their main goal was to free Warsaw before Soviet forces arrived. They planned to take key buildings and areas quickly.

The AK soldiers used guerrilla tactics. They set up barricades and fought in small groups. This made it hard for German forces to respond.

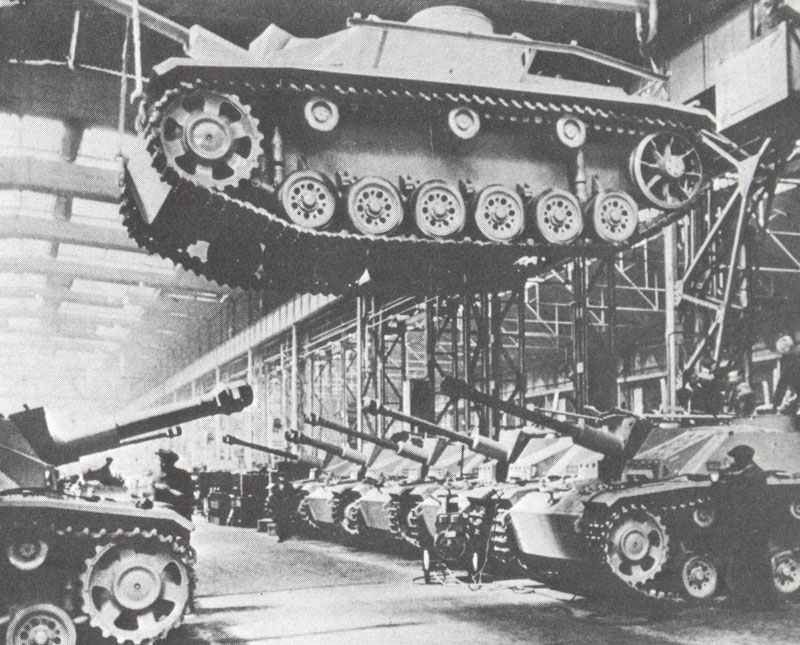

Insurgents hoped to get help from Allied powers. But support was limited. They had to rely mostly on captured weapons and homemade explosives.

Geographical Significance of Warsaw

Warsaw’s layout shaped the fighting. The Vistula River split the city. This affected how troops moved and supplies were delivered.

Tall buildings became important strongholds. Both sides fought to control these. High points let them see enemy movements and direct attacks.

The city’s narrow streets helped the Polish fighters. They knew the area well and could move secretly. But it also made it hard to move large groups or heavy weapons.

Urban combat was intense. Each block and building became a battlefield. This slowed the German advance but also caused major damage to the city.

Initial Conflict and Major Battles

The Warsaw Uprising began with coordinated attacks across the city. Polish resistance forces battled German occupiers in key districts. Fierce fighting marked the early days of the insurrection.

Outbreak of the Uprising

The Warsaw Uprising started on August 1, 1944 at 5:00 PM, known as “W-hour.” Polish resistance fighters launched surprise attacks on German forces throughout Warsaw. They quickly gained control of much of the city center.

Civilians joined the effort, building barricades and supporting the insurgents. The Polish flag flew over liberated areas for the first time since 1939.

Initially, the uprising made significant progress. However, German reinforcements soon arrived to counter the Polish advance.

Significant Engagements within Warsaw Districts

Fighting spread across Warsaw’s districts. Major battles took place in:

- Śródmieście (City Center)

- Wola

- Stare Miasto (Old Town)

- Żoliborz

- Mokotów

Polish forces used urban warfare tactics, setting up strongholds in buildings and sewers. They faced superior German firepower and armor.

The battle for Praga, on the east bank of the Vistula River, was particularly intense. Polish troops hoped to link up with approaching Soviet forces.

The Battle of Wola

The Battle of Wola was a crucial early engagement. German forces focused on retaking this western district to cut off the uprising from potential outside help.

Polish defenders fought bravely but were overwhelmed by German tanks and heavy weapons. The fall of Wola on August 5 marked a turning point in the uprising.

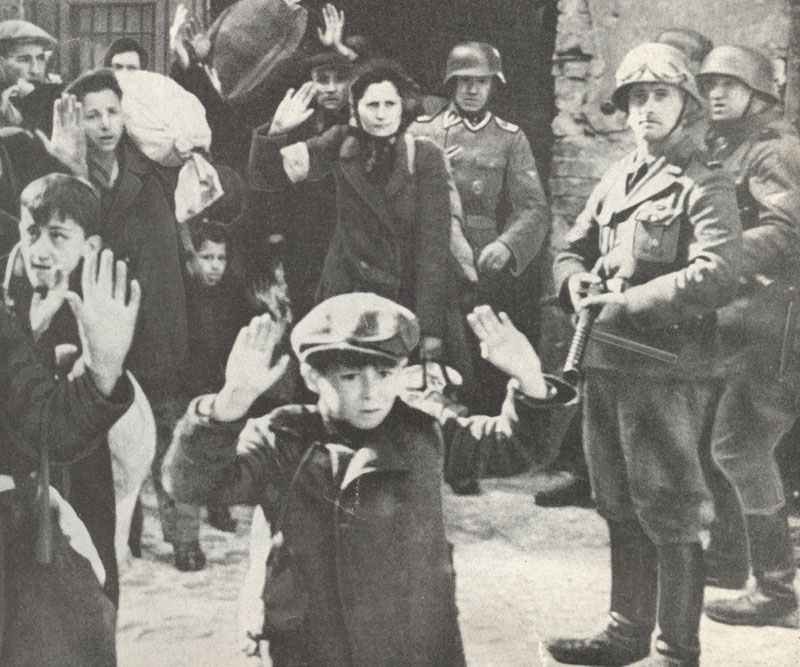

German troops committed atrocities against civilians in Wola, killing tens of thousands. This massacre shocked the world and highlighted the uprising’s high stakes.

Kaminski’s 29th Waffen Grenadier Division of the SS (Russian No.1), made up of Ukrainians, was sent to the Wola district to be deployed against the Polish Home Army during the Warsaw Uprising. Their appalling behavior led to demands for their replacement, even by other SS commanders. On a single day – August 5, 1944 – they are said to have murdered around 10,000 Polish civilians. Kaminski was later shot under unexplained circumstances and his ‘division’ was disbanded.

The 36th Waffen-Grenadier Division of the SS with its leader Dirlewanger was also deployed in Warsaw. Dirlewanger had been convicted of sex crimes before the war. His 4,000 butchers, rapists, looters and arsonists committed such terrible war crimes there within a very short space of time that the army and Waffen SS commanders also successfully enforced their dismissal.

The Role of Allied Forces

The Warsaw Uprising of 1944 saw varying levels of support from Allied forces. Western Allies attempted limited aid efforts, while the Soviet Union’s actions remained controversial.

Support from the Western Allies

The Western Allies provided some assistance to Polish resistance fighters during the Warsaw Uprising. They launched airlifts to deliver supplies, including food, ammunition, and grenades. These efforts faced significant challenges.

Only about half of the airdropped supplies reached the insurgents. The distance from Allied air bases made frequent resupply missions difficult. Churchill and Roosevelt pushed for more aid but struggled to overcome logistical hurdles.

Western support also included diplomatic pressure on Stalin to assist the Polish fighters. These efforts had limited success in changing Soviet policy toward the uprising.

Soviet Army’s Stance and Impact

The Soviet Army’s role in the Warsaw Uprising remains a subject of debate. As Soviet forces neared Warsaw, they halted their advance. This decision had a major impact on the uprising’s outcome.

Stalin refused requests from Western Allies to provide significant aid to the Polish resistance. The Soviet leader viewed the Polish Home Army with suspicion, seeing them as a threat to future Soviet control of Poland.

Soviet inaction allowed German forces to focus on crushing the uprising. This resulted in heavy losses for the Polish resistance and widespread destruction in Warsaw. The Red Army’s stance effectively sealed the fate of the uprising.

Social and Political Dynamics

The Warsaw Uprising of 1944 involved complex social and political elements. Civilians played a crucial role, while various resistance networks coordinated their efforts. The remaining Jewish community, though diminished, also participated in the fight against Nazi occupation.

Involvement of Civilians and Resistance Networks

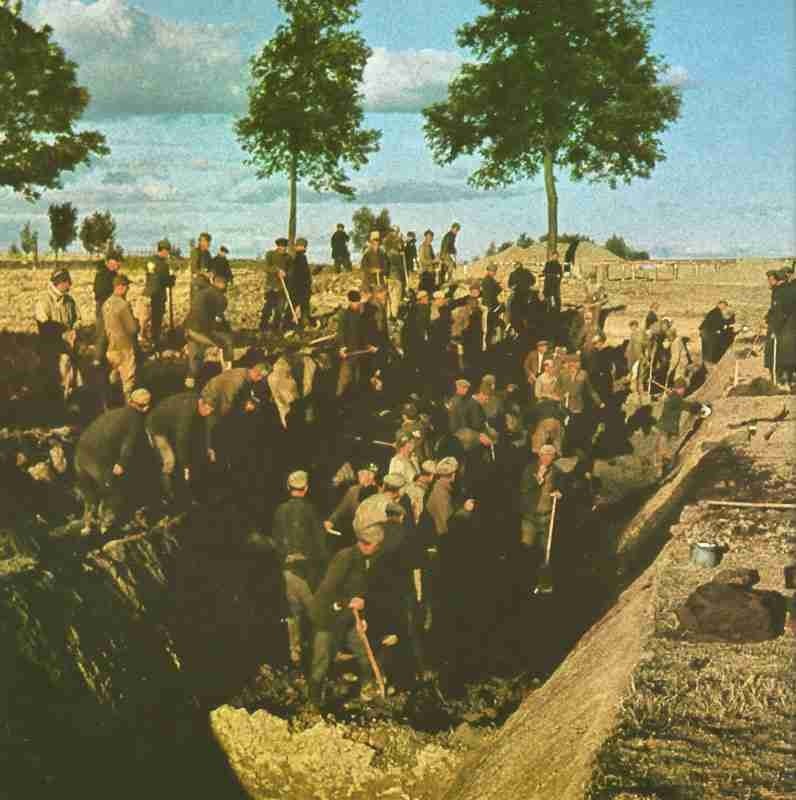

The Warsaw Uprising saw widespread civilian participation. People of all ages helped the resistance fighters. They built barricades, cooked meals, and cared for the wounded.

The Polish Underground State organized the uprising. This network included the Home Army and other resistance groups. They had spent years preparing for this moment.

Civilian support was vital. People opened their homes to fighters and shared scarce resources. Women took on combat roles alongside men. Children acted as messengers and lookouts.

The uprising united Warsaw’s residents against the German occupiers. It created a sense of solidarity and purpose among the Polish people.

Jews and the Polish Jews Community’s Participation

Survivors of the Jewish fighters played a significant role in the Warsaw Uprising. Many had survived the earlier Warsaw Ghetto Uprising in 1943.

These survivors joined Polish resistance groups. They fought alongside their non-Jewish compatriots against the Nazis. Jewish doctors and nurses worked in makeshift hospitals.

Some Jews hid their identity to avoid persecution. Others openly declared their heritage as they fought. The uprising gave them a chance to resist Nazi oppression.

Jewish participation highlighted the diverse nature of Polish resistance. It showed the commitment of all Warsaw’s residents to liberation.

Life under Siege

The Warsaw Uprising of 1944 saw civilians endure extreme hardship. People sought shelter underground and used creative means to survive and communicate.

Surviving in the Ruins and Cellars

Warsaw residents hid in cellars and ruins to escape German attacks. Food and water became scarce. People ate whatever they could find, including pets and zoo animals.

Makeshift hospitals were set up in basements to treat the wounded. Civilians helped by donating blood and assisting medical staff.

Despite harsh conditions, morale remained high. Underground newspapers and radio stations kept people informed. Cultural events like poetry readings and concerts lifted spirits.

The Sewers as Escape Routes

Warsaw’s sewer system became a vital network for the resistance. Fighters and civilians used the dark, cramped tunnels to move supplies and evacuate.

The sewers were dangerous. German soldiers pumped in water or tossed grenades to flush people out. Sewer gases and filth caused health issues for those traveling through.

Brave guides memorized the maze-like layout to lead groups. Some spent weeks underground, emerging covered in grime and sewage. The sewers saved many lives but also claimed victims who got lost or trapped.

German Retaliation

The German response to the Warsaw Uprising was swift and brutal. Nazi leaders ordered harsh measures to crush the rebellion and punish the city’s inhabitants. Their actions led to widespread destruction and loss of life.

German Military Response

The Germans sent in reinforcements to suppress the uprising. SS troops were deployed, even though many lacked proper combat training and were previously only used in the brutal anti-partisan operations behind the Eastern Front. This decision proved disastrous for Warsaw’s civilians.

Heinrich Himmler took charge of the German efforts. He gave orders to destroy Warsaw completely. The Nazis saw this as fitting retaliation for the insurgency.

German forces used heavy weapons against the rebels. They deployed tanks, artillery, and aircraft. These attacks caused major damage to the city’s buildings and infrastructure.

The Role of the German Garrison in Warsaw

The German garrison in Warsaw played a key part in fighting the uprising. They held strategic positions throughout the city. This allowed them to resist Polish attempts to take control.

The garrison coordinated with incoming reinforcements. Together, they worked to isolate rebel strongholds. They cut off supply lines and communication between insurgent groups.

German troops carried out mass executions of civilians. They aimed to terrorize the population and break the will to resist. These actions were part of the broader Nazi policy of crushing Polish resistance.

The garrison also helped implement the planned destruction of Warsaw. They systematically demolished buildings and cultural sites. This was done to erase Polish identity and history from the city.

The Aftermath of the Uprising

The Warsaw Uprising’s defeat had severe consequences for Warsaw, its people, and Poland as a whole. The aftermath brought immense suffering and destruction that shaped the future of the country.

Casualties and Prisoners of War

The Warsaw Uprising resulted in massive losses. About 16,000 Polish resistance fighters died, and up to 200,000 civilians lost their lives. Many were killed in mass executions.

Around 15,000 insurgents were captured as prisoners of war. The Germans sent them to various labour and concentration camps, including Auschwitz and Mauthausen-Gusen.

Thousands of Warsaw residents ended up in transit camps. From there, the Nazis deported them to forced labor in Germany or to concentration camps.

The Fate of Warsaw and Its Inhabitants

After the uprising, the Germans systematically destroyed Warsaw. They razed about 85% of the city to the ground.

The Nazis forced the remaining population to leave. They sent many to concentration camps or deported them to other parts of Poland.

By January 1945, Warsaw was almost empty. Its population dropped from 1.3 million before the war to just 1,000 people hiding in the ruins.

Long-Term Consequences for Poland and Eastern Europe

The uprising’s failure allowed the Soviet army to take control of Poland. This led to decades of communist rule in the country.

The destruction of Warsaw erased much of Poland’s cultural heritage. It took years to rebuild the city, and some historic sites were lost forever.

The uprising became a symbol of Polish resistance. It inspired future generations in their fight for independence from Soviet influence.

The events also affected Russian-Polish relations. Many Poles felt betrayed by the Soviet Union’s lack of support during the uprising.

Cultural Impact and Remembrance

The Warsaw Uprising of 1944 left a deep mark on Polish culture and memory. It inspired songs, art, and literature while shaping how future generations viewed the war. Museums and education programs help keep the uprising’s legacy alive.

Witness Accounts and Documentations

Many survivors shared their stories of the Warsaw Uprising. These accounts give a personal view of the events. Diaries, letters, and interviews capture the courage and struggles of those who lived through it.

Photos and films from the time show the destruction of Warsaw. They also reveal the bravery of its people. Artists have used these materials to create powerful works about the uprising.

Books and documentaries continue to explore this part of history. They help people today understand what happened in 1944.

The Warsaw Uprising Museum and Education

The Warsaw Uprising Museum opened in 2004. It teaches visitors about this key event in Polish history. The museum has many objects from the uprising. These include weapons, letters, and everyday items.

Interactive displays bring the uprising to life. Visitors can hear recordings of insurgent radio broadcasts. They can also see films made during the fighting.

Schools in Poland teach about the uprising. Many students visit the museum on field trips. This helps young people connect with their past. It also honors those who fought for Warsaw’s freedom.

Frequently Asked Questions

The Warsaw Uprising of 1944 was a crucial event in World War II that had significant impacts on Poland, the Allied forces, and the outcome of the war. Many questions surround this historic insurgency.

What were the primary objectives of the Warsaw Uprising?

The main goal of the Warsaw Uprising was to liberate Warsaw from German occupation. Polish resistance fighters aimed to take control of the city before Soviet forces arrived.

They hoped to establish Polish sovereignty and prevent Soviet domination after the war. The uprising was also meant to demonstrate Polish resistance against Nazi rule.

How many casualties resulted from the Warsaw Uprising?

The Warsaw Uprising led to massive loss of life. Estimates suggest around 150,000 to 200,000 Polish civilians died during the fighting.

About 16,000 members of the Polish resistance were killed, with another 6,000 badly wounded. German losses were approximately 8,000 killed and 9,000 wounded.

What were the strategic consequences of the Warsaw Uprising for the Axis and Allied forces?

The uprising tied up significant German forces, preventing them from reinforcing other fronts. This aided Allied advances elsewhere.

For the Allies, the failure of the uprising allowed Soviet forces to take control of Warsaw without Polish resistance. This strengthened the Soviet position in Eastern Europe.

What role did the Polish resistance play in the Warsaw Uprising?

The Polish Home Army led the Warsaw Uprising. They organized and executed the insurgency against German forces occupying the city.

Resistance fighters engaged in urban warfare, set up barricades, and established communication networks. They fought bravely despite being outnumbered and outgunned.

What was the impact of the Soviet stance on the outcome of the Warsaw Uprising?

Soviet forces halted their advance near Warsaw and did not provide significant aid to the Polish resistance. This decision greatly impacted the uprising’s outcome.

Without Soviet support, the Polish fighters were unable to overcome the German forces. The lack of assistance contributed to the uprising’s ultimate failure.

What was the aftermath of the Warsaw Uprising for the city of Warsaw?

After the uprising’s suppression, German forces systematically destroyed much of Warsaw. Up to 85% of the city was demolished.

Hundreds of thousands of surviving civilians were expelled from the city. Warsaw’s destruction was a devastating blow to Polish cultural heritage and urban infrastructure.

References and literature

Das Deutsche Reich und der Zweite Weltkrieg (10 Bände, Zentrum für Militärgeschichte)

Der 2. Weltkrieg (C. Bertelsmann Verlag)

Zweiter Weltkrieg in Bildern (Mathias Färber)

A World at Arms – A Global History of World War II (Gerhard L. Weinberg)