The monthly days of 1919:

Peace process from 1918 to 1923.

Such events remind us that the Great War settlement was more than just a matter of Germany, however much that country had dominated the former Central Powers and bulked foremost in the minds of peacemakers. The Treaty of Versailles with Germany (28 June 1919) was the first of six settlements with the defeated powers and the model for them all. No international agreement has undergone more analysis or remained so controversial. Not for the Allies the clear cut unconditional surrenders that concluded the Second World War whose own causes owed so much to the Peace Treaty of 1919.

The Treaty was divided into 15 parts containing almost 450 articles and numerous annexes. Germany lost 13% of her prewar territory and 6 million people or 10% of her population. By Articles 51-79 France regained Alsace-Lorraine (120,000 Germans departed by 1921) 47 years since their annexation. Belgium received the mainly German-speaking enclaves of Moresnet, Eupen and Malmedy (population about 70,000; Articles 32-34) that Prussia had gained in 1815. The Baltic port of Memel went to the new independent state of Lithuania (Article 99). Czechoslovakia received the Hultschin district (40,000 Germans emigrated). Poland gained West Prussia and the Posen area (Article 87); parts of Upper Silesia (by referendum in 1921) under Article 88; and a corridor to the Baltic Sea where the new Free City of Danzig (Articles 100-108) was to be administered by the League of Nations (its Covenant formed Part 1 of the Treaty). East Prussia was, therefore, cut off from the remainder of Germany. Northern Schleswig went to Denmark by plebiscite (Articles 109-114).

The 1000-square mile Saar Basin was put under League of Nations administration subject to plebiscite after 15 years. In the meantime, France was to control its valuable coal fields as direct reparation in kind for the damage done to hers (Articles 45-50). The Rhineland, containing Germany’s Ruhr industrial heart, was to be demilitarized and occupied for 15 years (Articles 42-43). Reparations were to be paid (Article 232) with an immediate payment of RM 20bn in gold by 1 May 1921. Reparations including handing over every merchant ship of 1600grt and over (half the ships of 1000-1600grt and a quarter of fishing vessels) to compensate the Allies for wartime losses.

All Germany’s colonies became League of Nations’ mandates for disposal to the victors (Article 22) and 20,000 German colonial settlers returned home. Economically Germany lost 45% of her coal (10 years of massive supplies to Belgium, France and Italy); 65% of her iron ore; 57% of lead; 72% of her zinc. The Kiel Canal (Article 380) and five major rivers became international waterways. A ban was placed on the union of Germany and Austria. Provision was made for the trial of the Kaiser and about 100 other war leaders (Articles 227-230) including Hindenburg; this was an unfulfilled but natural extension of the war guilt clause (Article 231). The German Army was reduced to a 100,000-strong volunteer force including a maximum of 4,000 officers (Article 160). Conscription was abolished (Article 173). No tanks, armored cars, heavy artillery, flamethrowers, poison gas, Zeppelins, military aircraft, air force or general staff were permitted. No arms were to be imported or exported. The Navy was limited to 15,000 men manning 6 old battleships, 6 light cruisers, 12 destroyers and 12 torpedo boats (Article 181). No new warship over 10,000 tons was to be built and no U-boats were allowed (Article 181).

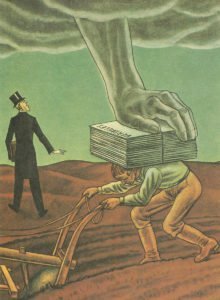

Little wonder that Germany signed under duress and protest. The High Seas Fleet was scuttled a week before the hated Diktat came into force. Much opinion in Britain and the USA turned against the harsh provisions to the extent that the US Senate never ratified the Treaty, itself a major weakness of the postwar settlement. Yet there were those who argued and still do that Versailles was too lenient, a compromise between the Big Four. The European Allies were keenly aware of their financial indebtedness to the USA ($10bn owed, only $2.7bn repaid 1920-32) and even the French felt obliged to refrain from claiming the Rhine frontier that Foch wanted. Versailles humiliated and hurt Germany, but, as events soon proved, did not permanently remove her capacity to wage aggressive war. Probably only the most ruthless partition of Germany into scores of 18th century-style small states and military occupation of a post-1945 scale and length could have achieved that.

The Reparations issue was to sour Allied-German relations into the 1930s. Fixed at £6.6bn plus interest in April 1921, the Weimar Republic promptly paid £50m but halted payments during the 1922 inflation crisis thus triggering a Franco-Belgian occupation of the Ruhr. The American-compiled Dawes Plan (April 1924) gave a loan to secure future payments and stabilized matters until the June 1929 Young plan cut the original figure by 75%, proposing annual installments until 1988. Germany made a first payment in May 1930 but the world economic depression and Hitler prevented anymore. All told Germany had paid RM21.6bn, or an eighth of the original demand, but received more in loans (mainly from the USA) to aid her economic recovery.

The Austrian Republic signed next at St Germain (10 September), admitting responsibility for the war (Article 77). Austria now consisted of only two-thirds of the former Habsburg German-speaking territories, losing 3.5 million Germans to Czechoslovakia and 250,000 South Tyroleans to Italy. Bulgaria’s fate was similar (Neuilly 27 November) but her reparations were the only ones wholly specified from the start – £90 million; 278,000 Bulgarians left the ceded territories.

Peace with Hungary was delayed by Bela Kunn’s Communist takeover until 4 June 1920 (Trianon). It proved the harshest of all the settlements. Privileged Dual Monarchy Hungary was reduced to one-third in area and population. She lost Transylvania to Romania, the most enlarged Allied Power, and her ancient capital of Pressburg (Bratislava) to the entirely new state of Czechoslovakia. No fewer than 280,000 Hungarians fled the ceded lands by 1924.

Turkey, alone of the defeated Central Powers, had the opportunity to mitigate her treatment by force of arms against a former Allied power – Greece. So crucial were these events to the modern republic that they are known as the Turkish War of Independence. Nevertheless, the main territorial difference between Sevres (10 Aug 1920) and Lausanne (24 July 1923) lay in the restoration of Turkey-in-Europe and the inviolability of Anatolia. The Great War had swept away the old Ottoman Middle East hegemony and Sultanate for good.

Conspicuous of course by her absence from the peace process was Russia. Yet the fear of a Bolshevized Europe was a great influence throughout. By the end of 1920 the Red Army had won the Civil War but had failed to export the Revolution on its bayonets. The Polish Army was the first foreign foe to defeat it conclusively until the Afghan mujahideen in 1989. The internally victorious but fragile Soviet Union began to recognize its new western neighbors and borders culminating in the March 1921 Treaty of Riga with Poland. Not so fortunate were the USSR’s southern neighbors in the Caucasus who had enjoyed a fractious independence since the upheavals of 1917. Between April 1920 and February 1921 Azerbaijan, Armenia and Georgia in turn became Socialist and Soviet Republics.

By 1924-25 non-Communist Europe could be said to be recovering prewar levels of prosperity and to have removed the most obvious scars of war. The political and emotional legacies of the Great War, and on the Western Front even its physical imprint, are with us still.