The monthly days of 1940:

- January 1940

- February 1940

- March 1940

- April 1940

- May 1940

- June 1940

- July 1940

- August 1940

- September 1940

- October 1940

- November 1940

- December 1940

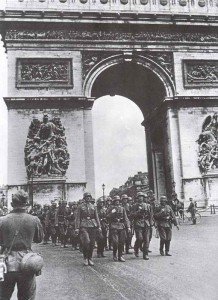

Western campaign 1940

On the day of the armistice of World War One on 11 November 1918, France was unquestionably the most powerful military power in the world. After more than four years of heroic, victorious struggle, the nation had together with her allies humiliated and disarmed the fatal enemy, Imperial Germany.

How could it be that a little more than twenty years later the French forces were defeated in a humiliating way in only six weeks? In addition, by a German ‘beginner’ army and Luftwaffe, which existed not more than five years!

The arrogance, the stubbornness, and the myopia of the French generals are quite incredible in the face of the past events.

For example, only a few days before Guderian’s Panzerkorps were flooded through the forests of the Ardennes, General Huntziger, Commander of the French Second Army, ordered the removal of all anti-tank obstacles from the roads in the area on the grounds that their existence was in contradiction with the orders. Even more incredible is still Marshal Petain’s despicable neglect of the value of armored vehicles and aircraft in a new great European war.

Inevitably, the senility of the French general staff, together with a weak government, the legacy of the almost uninterrupted series of political crises in France from February 1934 to the eve of the Hitler’s Blitzkrieg, had a drastic effect on the attitude towards rearmament and the morale and performance of the armed forces.

As early as 1931, the global economic crisis severely impaired the completion of the legendary Maginot Line. The extension of the line to the canal coast was refused on account of the government’s costs and restraint on the common frontier to Belgium.

The influence of Petain suppressed the creation of a French tank force, which could have dealt with Hitler’s Panzer divisions. Eight mechanized cavalry divisions were formed between 1934 and 1940, but these were not real armored divisions. In 1937 a complete armored division Cuirasse de Reserve (DCR) was approved, but the division existed only on paper until September 1939. Three other divisions, including de Gaulle’s 4th DCR, were hastily trained at the time when Hitler finally stroke at May 10th, 1940.

The impressive strength of the Maginot Line, which could actually be completed, along with a larger number of better armored and armed French tanks, led to the misunderstanding of the true situation until it was too late.

However, when it came to the condition of the French Air Force (Army de l’Air), no such self-deception was possible. The French aircraft industry had slipped through chaos in the years 1936 and 1937 by nationalization. The production figures did not recover from this until the spring of 1940. At the outbreak of war, too few modern fighters were found in France, and an obsolete bomber force, which could only be used at night.

It was true that the nationalized French aircraft industry was recovering spectacularly between January and June 1940. Airplanes were delivered to the Army de l’Air more quickly than they were able to take over, armament, radio equipment or trained crews. From the ‘French Spitfire‘, Emile Dewoitine’s slender D.520, one was produced every hour in June. Even bomber production rose steeply, with the ironic result that the French air force had more aircraft at the end of the Western campaign in 1940 than it initially had.

The effects of the fall of France were unpredictable and lasted well beyond the end of WW2. In the short run it seemed that Adolf Hitler’s once ridiculous dream that the German people should dominate Europe from the Atlantic to the Urals had become true.

In Hitler’s mind, it was also true for Great Britain that it must be a matter of weeks before the British understood their ‘hopelessness’ of their military position and agreed to give Germany a free hand in Eastern Europe in return for a Vichy-like ‘independence’ while maintaining their British Empire.

In the unlikely event that Britain would decide to continue the struggle, Germany could threaten or even invade it by an invasion or, alternatively, a paralyzing blockade with U-boats and airplanes from the newly gained naval and air bases along the entire European coastline, from Norway to the Bay of Biscay.

This double threat to the survival of Great Britain led to a terrible continuation of the war for the French after the fall of their country by Hitler, when Churchill ordered the Royal Navy 11 days after the armistice agreement to turn off the powerful French fleet off the North African coast to prevent it from falling into German hands.

When, in September 1940, a British and Free-French attack on the naval base of Dakar in French West Africa was followed by this ‘indignation’, the Vichy Collaboration Government ordered reprisals against Gibraltar and British shipping, and there was almost an actual declaration of war.

Thus, only three months after the fall of France, the former, close allies had become fierce enemies. Meanwhile, the forgotten French colonial garrison in Indochina fought a hopeless retreat fight against the Japanese, who wanted to profit quickly from the disaster of the French in their homeland.

In the long-term, the fall of France meant that WW2 would certainly become a long-term issue. In spite of the efforts of de Gaulle’s Free French, France had the only real hope of liberation from a fundamental change in the situation of Germany, for example by the intervention of the US or Russia.

The participation of the two great powers gave new impetus to the growing resistance movements within occupied France. The war entry of the US gave the longer-term prospect of a ‘Second Front’ and thus the hope of a definitive liberation of France.